A bill filed in the General Assembly would bring back North Carolina’s unaccountable film tax incentives. The incentives had sunset in 2014 and been replaced by a grant program, which is a budget line item rather than an open draw on the State treasury. House Bill 751 would restore the refundable tax incentives, something Gov. Roy Cooper sought in 2017.

Meantime, the General Assembly has already tripled the original grant program. In so doing, as the National Conference of State Legislators showed, North Carolina is driving the wrong way down the road as other states are getting away from incentivizing film productions.

Restoring the old film tax incentives, however, would not just keep North Carolina headed in the wrong direction. It would loop the seatbelt through the steering wheel and put a cinder block on the gas pedal.

There’s a reason states are trending away from film incentives. The programs are consistently revenue losers. State after state after state have found that they get pennies on the dollar for these “investments.”

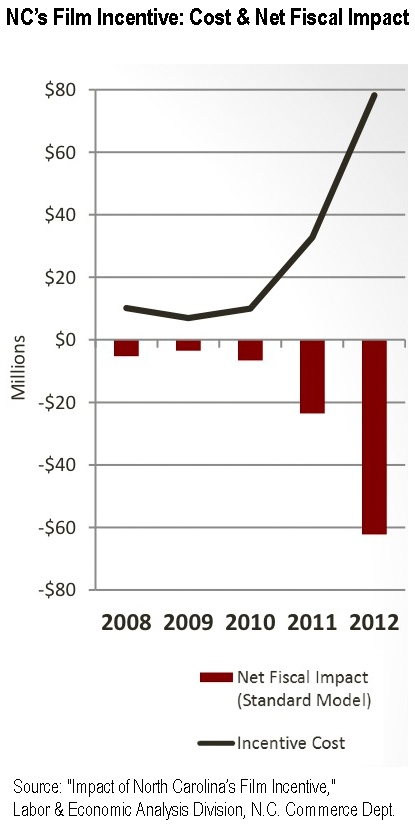

North Carolina’s program, the one this bill would bring back? It had a “net negative budgetary impact” returning only about 19 cents on the dollar:

As discussed in my 2012 report on the film tax incentives program, here are highlights of that old program:

- An income tax credit of 25 percent of qualifying production expenses, including employee fringe contributions and compensation of employees (up to $1 million per individual), regardless of tax residency, if their services are performed in North Carolina

- The production company must spend at least $250,000 on production in N.C. to qualify

- The income tax credit could be worth as much as $20 million

- The income tax credit is refundable

That last point was especially problematic. It extended tax “refunds” to outfits with basically no tax liability. It was a direct payment to the film production company without an act of appropriation. As the North Carolina Institute for Constitutional Law has argued, that’s likely unconstitutional:

The State Constitution prohibits the use of public money unless an appropriation has been made. Article V, Section 7, of the North Carolina State Constitution states in pertinent part:

Drawing Public money.

(1) State treasury. No money shall be drawn from the State treasury but in consequence of appropriations made by law, and an accurate account of the receipts and expenditures of State funds shall be published annually.

N.C.G.S. § 105-151.29(e) clearly and unambiguously authorizes the payment of public money to private film production companies as part of a so-called “refund.” The central constitutional question then is whether the General Assembly has appropriated money for payments to film production companies. The answer, as explained below, is no.

So just get rid of the refundability portion and then it’s no problem, right? Well, that’s the grant program, which film incentives backers gripe about. They had made it clear for years how important refundability is to incentivizing film productions.

Research shows that film incentives programs only benefit outside film production companies; they aren’t associated with actual growth to the state’s economy.

Even judged on its supposed intent, a film tax incentive beyond 10 percent furthers a wealth transfer from the state’s citizens to out-of-state film producers without any corresponding benefits to the state.

Also, let’s not forget that the programs embolden out-of-state productions and Hollywood activists to bully state lawmakers into enacting their preferred social agenda, not just their preferred incentives package. (Just ask Georgia this year, if you don’t remember 2016.)

Research bears this out, too. Film tax incentives are shown to encourage rent-seeking behavior and lead to “an extortive political economy.”

A public-choice problem

So if the things are net money losers for the state, only benefit outside film production companies, and lead to an extortive political economy, why would any politician bother?

Because it’s a public-choice problem. A small group stands to benefit from the concentrated revenue culled from a much larger group of taxpayers. The cost per individual taxpayer is a pittance, and they’re too busy to fuss about a pittance. The gain to the small group is significant, making it definitely worth their while to lobby the politicians to get it. The politicians get lobbied and courted on only one side of the issue.

Cronies love public-choice problems. As explained by economists James D. Gwartney, Richard L. Stroup, and Russel S. Sobel in Microeconomics: Private and Public Choice (with an ironic nod to Adam Smith) :

If you were a vote-seeking politician, what would you do? Clearly, little gain would be derived from supporting the interest of the largely uninformed and uninterested majority. In contrast, support for the interests of easily identifiable, well-organized groups would generate vocal supporters, campaign workers, and, most important, campaign contributors.

Predictably, politicians will be led as if by an invisible hand to support legislation that provides concentrated benefits to interest groups at the expense of the disorganized groups (such as taxpayers and consumers). This will often be true even if the total community benefit from the special-interest program is less than its costs. Even if the policy is counter-productive, it may still be a political winner.

Being counterproductive, a revenue-loser, but still a political “winner” somehow, that’s a public-choice problem. It can even unite the political Left and Right against it, yet live on because of its “winning” blend: serving the interests of vote-seeking politicians and rent-seeking cronies, but not the state or its citizens.

Of course, the film grant program is a public-choice problem, too. Reverting it back to the film tax incentives program would make that problem worse, with less oversight and more empowerment of the special interests. The proper solution for good government in North Carolina is to eliminate the film grant program without restarting film tax incentives.