- North Carolina’s unique county clustering process is a way of balancing constitutional requirements of keeping counties whole and having equal populations of legislative districts

- The county clustering process is simple in principle but can be complex in application

- The whole county provision of the North Carolina State Constitution and redistricting criteria adopted by the General Assembly substantially influence how districts can be drawn within county clusters

Like many other states, North Carolina must minimize dividing counties when drawing state legislative districts. North Carolina does it through a unique process called county clustering, which is also called county grouping. Here are the basics of that process.

Preparing to select county clusters

Article 2, Sections 3 and 5 of the North Carolina State Constitution dictate that “no county shall be divided” when forming state legislative districts (the “whole county provision”). However, it also requires that districts be as equal in population as possible.

How to balance the whole county and equal population provisions of the North Carolina Constitution was laid out in Stephenson v Bartlett (2002). On page 44 of Stephenson, the court stated that “The intent underlying the [whole county provision] must be enforced to the maximum extent possible” and prescribed a process to achieve that. The process starts by grouping counties into clusters (groups) that contain the minimum number of districts within the minimum number of counties.

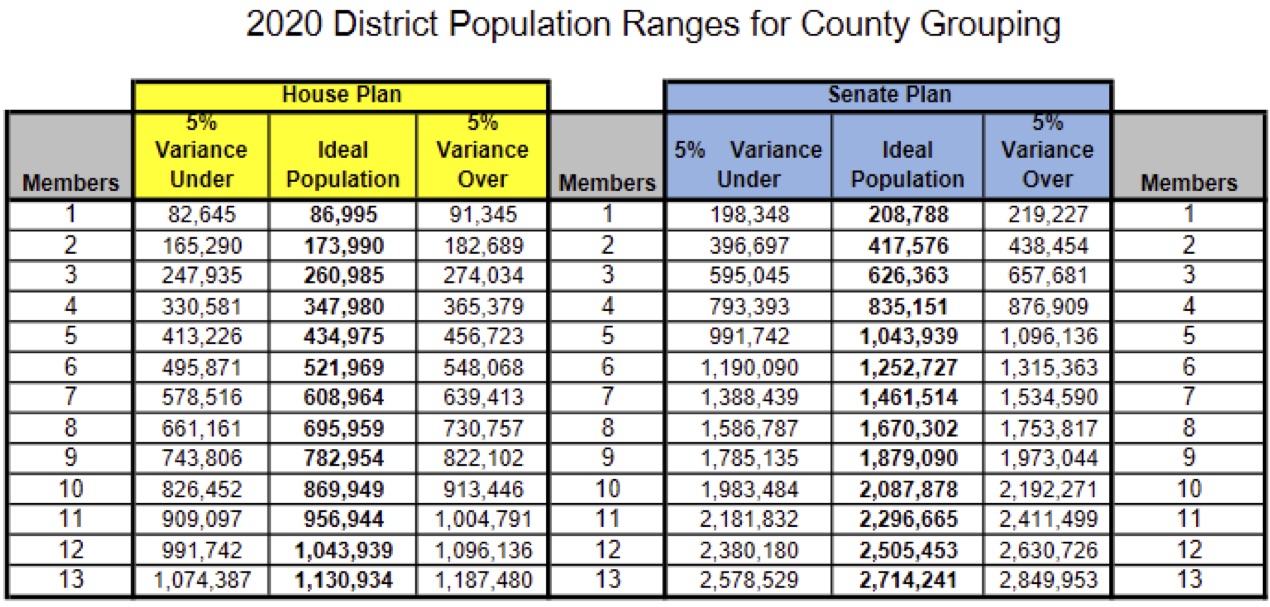

The first step is finding the ideal population size for legislative districts. That is found by dividing the state’s population in the 2020 census (10,439,388) by the number of state legislative districts. As seen in Figure 1, the ideal population for each of the 120 State House districts is 86,995. The ideal population for 50 State Senate districts is 208,788.

Figure 1: Population ranges for county groups

Source: North Carolina General Assembly

The population of state legislative districts may vary from the ideal population by up to 5%, meaning that a North Carolina House district can have a population between 82,645 and 91,345.

Creating county clusters

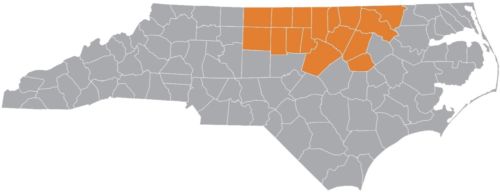

To demonstrate how the county clustering process works, I will use a section of north/central North Carolina (Figure 2) as an example using North Carolina House districts. County population numbers are from the U.S. Census Bureau as reported by Carolina Demography.

Figure 2: North Carolina counties used in county grouping example (orange)

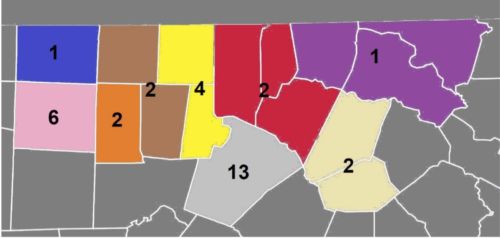

The process starts by seeking one-county clusters, ideally a single district in a single county. There is only one such county in the example area: Rockingham (population 91,096, marked blue in Figure 3). Next is to find counties that can contain two whole districts. Again, there is only one county that qualifies: Alamance (171,415, orange). That process continues until the list of counties that can contain a whole number of districts within their boundaries is exhausted. There are two other such counties within the example area: Guilford (541,299, pink) with six districts, and Wake (1,129,410, light gray) with 13 districts.

After the list of counties that can contain a whole number of districts is exhausted, the next step is to locate groupings of two counties that can hold a whole number of districts. Caswell County (population 22,376) is too small to contain a North Carolina House district, and Orange County (148,696) is too big for one district while too small for two. Their combined population (171,072), however, is within the population range of a two-district grouping (marked brown in Figure 3). Nash and Wilson counties (combined population 173,754, cream color) also form a two-district cluster, while Durham and Person counties (363,930, yellow) form a four-district cluster.

Figure 3: Likely county groupings in the example area, based on county populations

Note: Each color represents a grouping (cluster), and each number represents the number of North Carolina State House districts in each grouping.

The area covered in Figure 3 also has two three-county groupings. Warren, Halifax, and Northampton counties (84,735, purple) form a one-district cluster, while Granville, Vance, and Franklin counties (172,143, red) form a two-county cluster.

An example of drawing districts within a county cluster

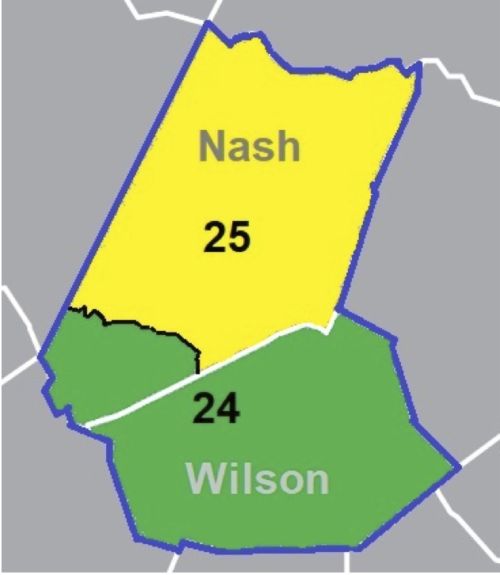

For an example of how the county clustering process affects redistricting, let’s look at the Nash-Wilson grouping.

The two counties would likely be joined in a two-district grouping. Since the criteria in the Stephenson case require that counties remain whole to the “maximum extent possible,” the smaller county in a two-district, two-county cluster would remain whole. That means Nash County (94,970) would be divided while Wilson County (78,784) would not be split.

Figure 4 shows a possible drawing of North Carolina House districts 24 and 25 in the Nash-Wilson cluster. It satisfies the redistricting criteria adopted by the General Assembly on August 12. The districts are roughly equal in population (87,220 in the 24th, 86,534 in the 25th). They are reasonably compact given the geography of the county cluster. No precincts are divided. No municipalities are divided by the division of Nash County. Finally, the two incumbents in the cluster (James D. Gailliard and Linda Cooper-Suggs) are not double-bunked into the same district.

Figure 4: Possible North Carolina 24th and 25th House districts in the Nash-Wilson county cluster

Both districts would favor Democrats. Using the method used to calculate the Civitas Partisan Index (which was highly accurate in 2020), the 24th District would favor Democrats by 4.2%, and the 25th would favor Democrats by 7.6%. Legislators could draw one safe Democratic and one safe Republican district there. Those districts would not be compliant with either the redistricting criteria established by the General Assembly or the Stephenson criteria, however.

Understanding North Carolina’s county clustering process is important to knowing how redistricting is done here. Knowing that process will help citizens understand, for example, that Durham County must share a North Carolina House district with Person County but is barred from sharing House districts with any other counties. Understanding the county clustering process will help citizens better evaluate district maps the General Assembly produces.

Read “A ‘Stephenson’ Explainer” by Blake Esselstyn for more information on how county groupings are formed. To see projections of county groupings for the whole state, see reports from The Differentiators and Christopher Cooper et al.