The government response to the coronavirus pandemic has thrown millions of Americans out of work and has led to skyrocketing numbers of unemployment claims. North Carolina has seen over one million initial claims for unemployment benefits, and the Division of Employment Security was unable to handle the crushing load, producing a lag in benefits that exacerbated the state’s existing inefficiencies.

The shortcomings have infuriated applicants and led Gov. Cooper to replace the manager of the state’s unemployment insurance system Lockhart Taylor with longtime Democratic insider Pryor Gibson. I argue that Gov. Cooper and others scapegoated the problems on the unemployment chief who directed a system that was not built to handle the full weight of the unemployed population of North Carolina in good times, let alone the crushing weight of unemployment courtesy of the current pandemic.

North Carolina has the lowest recipiency rate – the share of unemployed workers receiving benefits from state programs – in the country. Only around 10% of all unemployed North Carolinians received unemployment benefits in 2019. In March, NC Justice Center Executive Director Rick Glazier and President of the North Carolina State AFL-CIO MaryBe McMillan wrote, “the system is near the bottom of the national pack in terms of its capacity to assist workers.” National unemployment data suggest they incorrectly interpreted the state’s low recipiency rate as an inability to provide benefits to people. Instead, it seems North Carolinians simply did not see the value in applying in the first place.

States vary widely in every aspect of their unemployment insurance program. Massachusetts pays up to nearly $1,200 for a claim, while Mississippi’s benefits are capped at $350. Montana allows claimants to receive benefits for 28 weeks, while North Carolina and Florida only offer 12 weeks of coverage. Several factors influence low recipiency rates, but the most commonly cited factor, systemic inefficiency, is not among them.

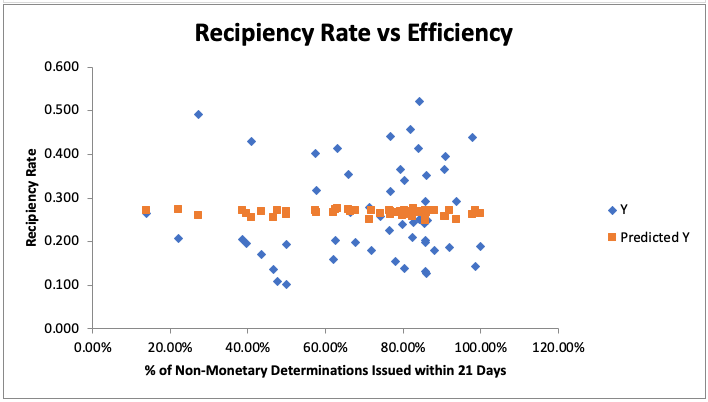

The Employment & Training Administration (ETA) of the U.S. Department of Labor publishes data on the processing time for non-monetary determinations, that is, determinations regarding overall eligibility rather than the amount of benefits. This can be used as a proxy for the system’s efficiency. There is no relationship between the percentage of determinations a state makes within 21 days (the standard timeframe used to measure timeliness for determinations) and its overall recipiency rate.

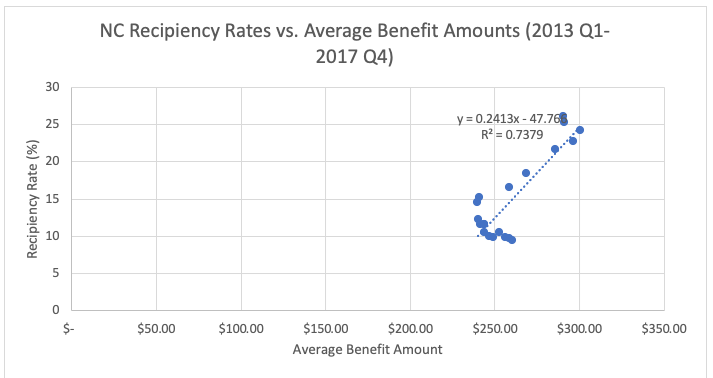

This trend holds within North Carolina as well. From 2013 to 2017, a period during which North Carolina implemented several changes to its unemployment insurance system, the state saw the percentage of benefits paid within 14 days crater from 80% to 40% before rebounding to around 70%. ETA data show that during that same period, the recipiency rate steadily declined, seemingly unaffected by the drastic changes in payment efficiency. Recipiency rate does not appear to be a function of efficiency. What, then, does lead to low recipiency rates?

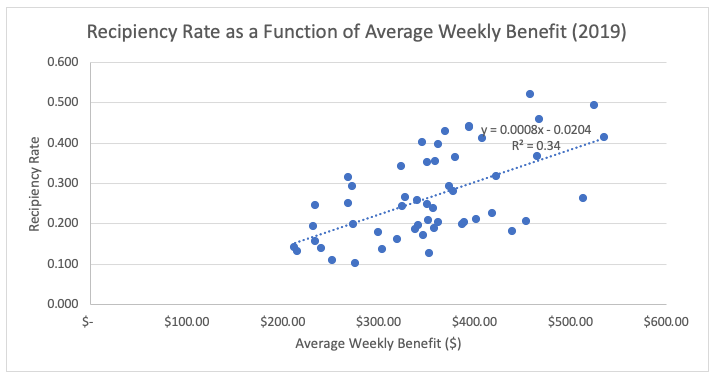

There aren’t many factors that present unusually large correlations, due mostly to the fact that there are only 51 data points (50 states and the District of Columbia) in any given year. But there are a few factors that seem to be related to recipiency rate. Among the strongest of these is the average weekly benefit. The more benefits a state offers, the higher its recipiency rate. This suggests that employees are not kept from unemployment insurance but rather are electing not to claim benefits.

Data from 2013 to 2017 further supports this conclusion. As benefit amounts increase, recipiency increases. It is, therefore, likely that North Carolina’s system is not harmed by its inefficiency. Indeed, the system has grown more efficient, even as recipiency has declined. Instead, the state has led would-be unemployment recipients to decline applying in the first place. North Carolina’s unemployment insurance system should look for ways to be more efficient, but to assert that inefficiency is causing its low recipiency appears to be incorrect.

Due to the increase in benefits and the decrease in available work due to the CARES Act, there may, in fact, be an increase in North Carolina’s recipiency rate, even as the state’s inadequate system has had to process an unprecedented number of claims. However, these delays are not the product of mismanagement by the unemployment chief but rather of a system built to handle considerably fewer claims than its peers – and far fewer than it faces now.