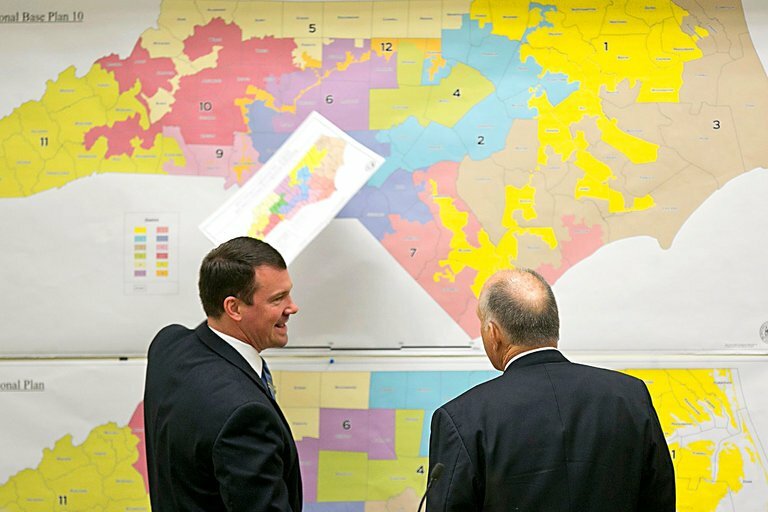

The North Carolina Supreme Court heard oral arguments on a pair of redistricting lawsuits on February 2. A quick ruling on the case is expected. The ruling could alter some or many of North Carolina’s 14 congressional, 50 state Senate, and 120 state House districts.

How the Court Could Rule

The court, which currently has a 4-3 Democratic majority, has a range of options, from upholding the maps to overturning decades, if not centuries, of precedent. Here are some possible outcomes, ranging from the most positive for Republicans to the most positive for Democrats.

Uphold the maps: The trial court hearing the case upheld the maps the General Assembly drew last fall. That court determined that district map boundaries are “political questions and thus non-justiciable.”

Based on ratings of the Civitas Partisan Index and other analyses, here are the likely partisan leanings of districts in the current maps:

- Congress: 10-4 Republican

- NC Senate: 28-22 Republican

- NC House: 69-51 Republican

Impose median maps: This would incorporate data from some of the plaintiffs’ expert witnesses to create guidelines for map drawers (legislative or court-appointed) to follow. For example, one expert witness for the plaintiffs found that the median congressional map was 9-5 Republican while another found 8-6 was slightly more likely than 9-5.

There are a couple of questions that justices would have to answer as part of their ruling to further define what median maps are. First, should map drawers seek to keep municipalities together when drawing maps? Second, should map drawers be required to draw median maps at the county-cluster level as well as the statewide level? Answering “no” to both of those questions would be more favorable to Democrats and is basically what the court imposed in Common Cause v. Lewis in 2019. Gov. Roy Cooper and Att. Gen. Josh Stein asked the court to only consider median outcomes at the statewide level.

The court could also order some county clusters to be changed.

Here is a range of possible district partisan leanings based on median outcomes, using Dave’s Redistricting Atlas (DRA) program:

- Congress: 9-5 or 8-6 Republican

- NC Senate: 27-23 or 26-24 Republican

- NC House: 65-55 to 63-57 Republican

Impose a proportional representation scheme: It is highly unlikely that the court would go this route. Cooper and Stein noted in their brief asking the court to overturn the current maps that “our constitution does not require absolute proportionality between parties’ statewide voter share and their composition in the legislature.” It is included here because this is often what people mean when they say they want “fair” maps.

If the court did seek to impose proportionality on our single-member district system, it would open other questions. What races would be used to determine proportionality? Would the court impose proportionality strictly based on statewide race outcomes or would the proportionality scheme incorporate an understanding of the relationship between election outcomes and legislative seats in our single-member district system?

Here is a range of possible district partisan leanings, based on the answers to those questions:

- Congress:: 8-6 Republican or 7-7

- NC Senate: 27-23 or 26-24 Republican

- NC House: 66-54 to 62-58 Republican

Impose Plaintiff maps: One group of plaintiffs, led by the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters (NCLCV), submitted their own “optimized” maps for the court to consider. Analysis of their congressional map found that it would favor Democrats 8-6. Their North Carolina Senate and House maps similarly favored Democrats, although not to the point of giving them an advantage in a majority of districts.

Here are the partisan leanings of the NCLCV maps (again, using DRA):

- Congress: 8-6 Democratic

- NC Senate: 26-24 Republican

- NC House: 62-58 Republican

Upcoming Elections Are a Potential Restraint on Judicial Overreach

Even if the court’s Democratic majority overturns the maps enacted by the General Assembly, the 2022 election will likely restrain how far they are willing to go to help Democrats with new maps.

First, there are two Supreme Court seats up in the 2022 election, both of which are currently held by Democrats. Justice Robin Hudson is retiring while Justice Sam Ervin IV is running for reelection. 2022 is shaping up to be a good election year for Republicans, meaning that they will likely take Hudson’s seat, giving them a majority on the court. While Ervin IV has the advantage of incumbency, he will need some moderate-to-conservative votes to win. Voting for an extreme outcome in this case would make it harder for him to paint himself as a moderate and would boost grassroots support and funding for his opponent in the general election.

Also, Republicans are almost certain to win majorities in the General Assembly, no matter what maps are used in this election. If they feel the court’s ruling in the redistricting case is onerous, they would draw new congressional districts next year. After the inevitable lawsuit, those districts would be heard by a North Carolina Supreme Court with a new Republican majority willing and able to overturn any precedent this case sets. A more moderate ruling (one that imposes a 9-5 Republican congressional map, for example) would lessen the chance that the legislature would go that route, especially if Democrats in the court could get a Republican to join them on the ruling.

(I don’t think many people would be surprised to learn that judges are strategic actors.)

There are other things the justices could do, such as overturning the county clustering system imposed by Stepheson v Bartlett. The same strategic considerations noted above would likely prevent such extreme rulings, however.

Considering the current political composition of the court and strategic factors, the most likely outcome is for the court to overturn the enacted maps but impose a more moderate median district outcome regime than that imposed by judges in 2019.