The lack of attention given to the national debt crisis by politicians, pundits, and policymakers is always disheartening to me – and it is a crisis. Make no mistake, Republicans and Democrats are guilty of contributing to this problem. The importance of responsible government spending was lost several decades ago and only a handful of politicians seem willing to raise awareness on this issue.

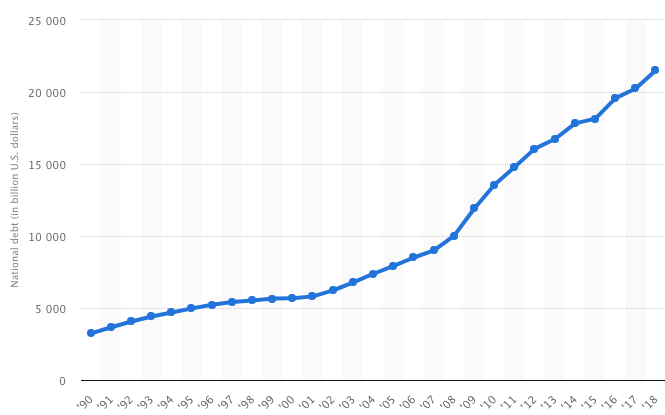

Here is a chart showing total U.S. public debt over the past two decades:

The CBO projects that federal debt held by the public will be 92 percent of gross domestic product by the year 2029. Given the trajectory of yearly deficits, it doesn’t take an economics degree to realize this isn’t sustainable.

What can explain this reality? Look no further than public choice economics to understand how this could happen and why none of our elected officials seem concerned with the long-term financial stability of our country. My colleague Jon Sanders writes often about public choice theory (See here, here, and here). Here is an explanation of public choice theory from one of his recent blog posts:

The wishful thinking it displaced presumes that participants in the political sphere aspire to promote the common good. In the conventional “public interest” view, public officials are portrayed as benevolent “public servants” who faithfully carry out the “will of the people.” In tending to the public’s business, voters, politicians, and policymakers are supposed somehow to rise above their own parochial concerns. …

But public choice, like the economic model of rational behavior on which it rests, assumes that people are guided chiefly by their own self-interests and, more important, that the motivations of people in the political process are no different from those of people in the steak, housing, or car market. They are the same human beings, after all. As such, voters “vote their pocketbooks,” supporting candidates and ballot propositions they think will make them personally better off; bureaucrats strive to advance their own careers; and politicians seek election or reelection to office. Public choice, in other words, simply transfers the rational actor model of economic theory to the realm of politics.

Examining the issue of the public debt through the prism of public choice theory helps explain why politicians would be so unwilling to do any of the following: confront the unsustainable spending pattern, slow the growing yearly rate of spending increases on public programs, or try to come up with long-term solutions to this issue.

The video below sums up some of the major problems policymakers will face in the coming years. Namely, Social Security and Medicare spending:

I’m not going to hold my breath waiting for a majority of Congress to take this issue seriously and try to come up with a plan. But future lawmakers will have to make tough choices and future generations will be paying for the recklessness of current spending patterns.