Kevin Hassett explores in the latest print edition of National Review the consequences for former Soviet republics and client states when they decided to model their economies on either western European models or their former Russian overseers.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, former Soviet and Eastern Bloc countries chose between two distinct paths. Ten Central and Eastern European nations (the so-called CEE-10) made integration with the European Union a top priority. The rest, like Ukraine, moved much more slowly toward Western standards, and some even settled under a new Russian umbrella.

Prior to the breakup, Eastern Europe was underdeveloped relative to the West, mostly because of the failure created by central planning. When a market economy is unleashed in such a setting, “convergence” of the standard of living to that of the developed world can be quite rapid. If the U.S. wants to grow sharply, it needs to push the very frontier of what is possible farther out. A former Soviet or Eastern Bloc country, on the other hand, could grow rapidly simply by copying the developed world. Some did.

A large academic literature has emerged analyzing the impact of “going west.” The literature documents that those nations that assimilated into the EU saw dramatic economic growth. A recent EU study co-authored by Ryszard Rapacki and Mariusz Prochniak of the Warsaw School of Economics, for example, concluded that full convergence of the CCE-10 is so far along that it might be complete in as little as eight years.

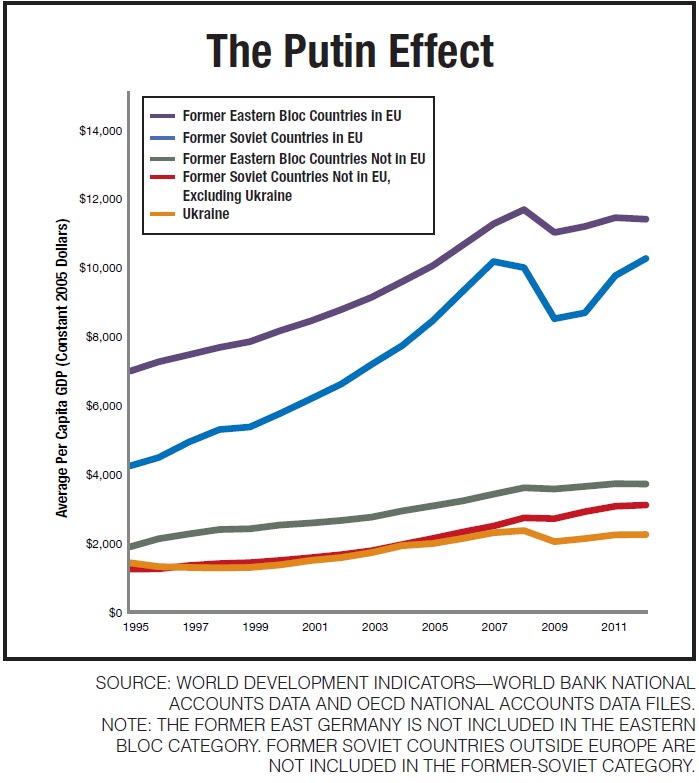

The countries, like Ukraine, that failed to take that path have stagnated. The nearby chart documents how radically different their experience has been. The chart plots real per capita GDP (in 2005 dollars) for former Soviet and Eastern Bloc countries other than Russia. The purple and dark blue lines on the top illustrate the findings of the study just mentioned. Income per capita has grown sharply since the mid 1990s, more than doubling for the former Soviet countries, and increasing about 50 percent for the Eastern Bloc countries (such as the Czech Republic) that have joined the EU.

The three lines on the bottom of the chart depict what has happened to those nations that have not joined the EU. Each of these countries has stagnated, seeing a standard of living that has barely budged since the fall of the USSR. The experiences have been so different that the increase in welfare for citizens in former Soviet countries that have joined the EU is larger than today’s level of welfare for countries that have not.