- Signed by Gov. Cooper, HB 951 puts his policy goal of 70% reduction of CO2 emissions into law, allows multiyear rate plans for utilities, and lets small solar facilities amend and extend their contracts with utilities

- Elements of the new law portend large increases in electricity costs for consumers in North Carolina, but its intent was to “ensure reliable energy generation with fiscal responsibility” and prevent even worse rate hikes

- Only through a very strict adherence to the law as written can that goal be achieved

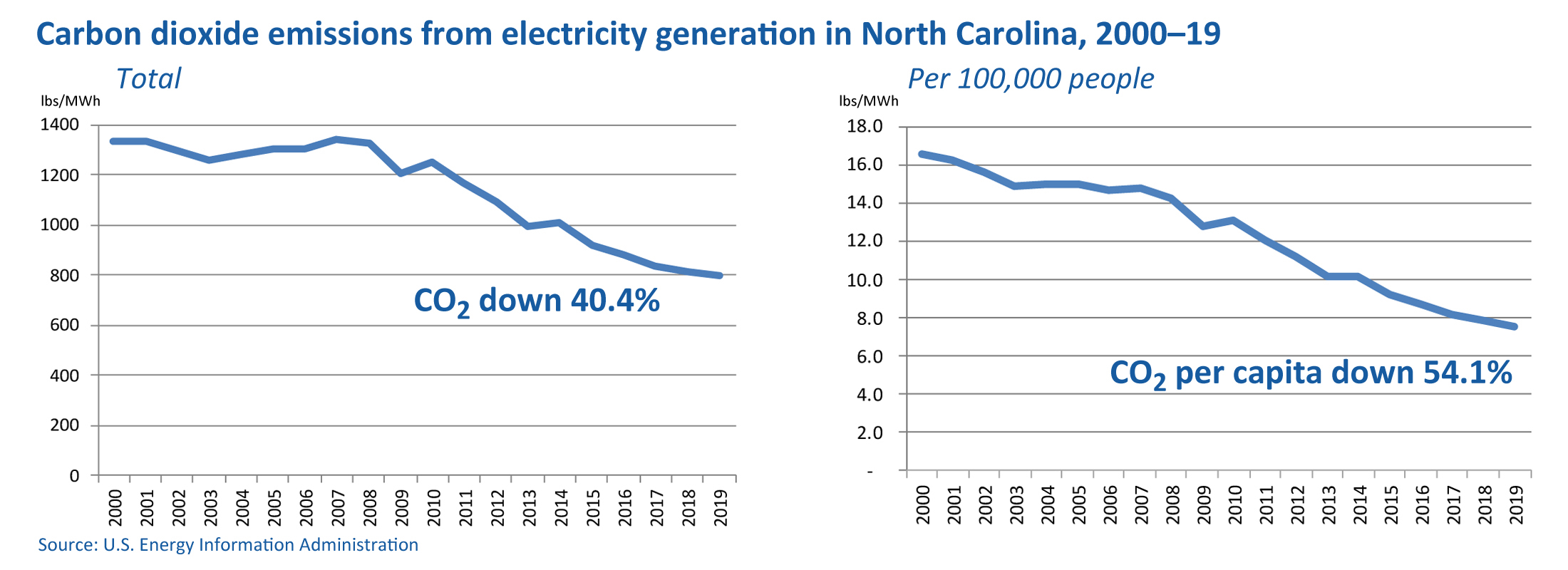

Thanks to market decisions, not government edicts, North Carolina has seen major reductions in CO2 emissions this entire century:

Nevertheless, a bill making major changes in electricity generation and provision (House Bill 951) passed overwhelmingly in the Republican-led General Assembly and was signed into law by Gov. Roy Cooper. HB 951 was a “stakeholders” bill, and a big stakeholder was the governor himself, as the bill puts into law the governor’s arbitrary goal of 70% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by 2030. Other stakeholders include environmental special interests, whose main objection is that utilities Duke Energy and Dominion Energy were also involved.

The new law’s measures include:

- Requiring the North Carolina Utilities Commission (UC) to “take all reasonable steps” to achieve by 2030 a 70% reduction in CO2 emissions from 2005 levels.

By the end of 2022, the UC must develop a “Carbon Plan” in consultation with the utilities and stakeholders to achieve the CO2 reduction goal. This plan must be revisited by the parties every two years to see if it needs adjustment. - Letting the UC allow what’s called performance based regulation to a utility that allows it to go outside the UC’s established, statutory ratemaking process.

The intent is to “decouple” the utility’s revenue from how much electricity is used by consumers and link it instead to a “performance incentive mechanism” that rewards the utility’s “performance in targeted areas consistent with policy goals” such as emissions reductions, increases in efficiency, etc. (think of having to pay McDonald’s not just for your cheeseburger, but also for how much fewer cheeseburgers people are eating). - Allowing the utilities as part of this PBR to set multiyear rate plans.

These plans would set rate increases in advance over several years without the utility needing (as it does now) to make yearly individual rate applications to be reviewed by the UC. The bill stipulates that the “annual rate of increase” in subsequent years — expectation for rate increases written in state law — can’t exceed 4%. Electricity costs could go up quickly for consumers. In 2020, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the average monthly North Carolina electricity bill was $118.44, so a next-year increase of 4% would make consumers pay $57 more for electricity that year. Adding another 4% increase would make their annual cost $116 more. And that’s just by the third year. - Requiring (among other rules changes) the UC to have utilities use bonds to finance the costs for retiring “subcritical coal-fired electric generating facilities” at 50% of the remaining net book value.

This bond financing comes “with any remaining non-securitized costs to be recovered through rates” (think of having to pay McDonald’s a surcharge for removing fries from the menu.) - Letting the UC offer a one-time extension of utilities’ contracts with small solar providers.

The utilities are required under federal law to purchase all the power these providers produce whenever they produce it, regardless of the utilities’ need for power at those times. At 10 years, North Carolina already has the longest contracts in the Southeast, and they are fixed rates so consumers don’t benefit from the supposed “falling costs of solar.” This change lets small solar facilities tack 10 years on to the end of their current contracts (purchase power agreements) if they amend their contract rates with the intent being both an immediate reduction and a long-term reduction in consumer’s electricity costs.

Much higher electricity prices are coming regardless; how much worse will they get?

Before this law, Cooper and his administration had already broken pledges to North Carolinians, putting them on the hook for 90% of the estimated $9 billion coal-ash cleanup cost. Big rate increases were already on the way.

Meanwhile, Cooper was developing his budget-busting “Clean Power Plan” with people who considered “clean, cheap, abundant energy” to be just “a little short of disastrous” and with 164 environmental and other “stakeholder” organizations who openly admitted that “Affordability” and “Reliability” were not “values to prioritize.”

Those anti–affordable electricity ideologies are in direct opposition to North Carolina state law, which recognizes that “the rates, services and operations” of electric power utilities are “affected with the public interest” — and therefore the state’s policy is “adequate, reliable and economical utility service to all of the citizens and residents of the State” as well as “the least cost mix of generation and demand-reduction measures which is achievable.”

As shown in the Locke Foundation’s “Energy Crossroads” report by Jordan McGillis, the closest approximation of Cooper’s plan by Duke would increase electric bills for North Carolina households by $411 per year.

Can this new law ward off even worse electricity hikes?

By putting Cooper’s plan’s goal into law in the way HB 951 did, however, it would help “ensure reliable energy generation with fiscal responsibility,” in the words of bill sponsor Sen. Paul Newton. Can it?

It is possible — but only by strict adherence to the law’s text.

For example, the law seeks to chart a “least cost path consistent … to achieve compliance with the authorized carbon reduction goals.” Understand that is not “least cost” in the way pre-existing state law considered it.

Originally, it was the “least cost mix of generation” (provision of electricity); the new law favors the “least cost path” to achieve a “policy goal” (70% reduction in CO2 emissions). Given the enormous range in cost and reliability among Cooper’s preferred energy sources and others, which includes zero-emissions nuclear, the difference here is like the difference between having a low-cost, healthy meal vs. seeing the least-cost path consistent with having fresh lobster flown in from Maine and served with caviar. We’re off the “least cost path” for electricity provision and now trying to do an expensive thing the least expensive way.

Strict adherence to “least cost path” would, as demonstrated in Locke’s “Energy Crossroads” report, require more efficient, reliable low-emissions (natural gas) and zero-emissions (nuclear) sources.

The law does point back to the “least cost mix” standard in long-term planning with regard to the Carbon Plan, and it includes that it must also “Ensure any generation and resource changes maintain or improve upon the adequacy and reliability of the existing grid.” Strictly followed, such a standard would prevent a great amount of expensive new solar and wind generation from being placed on the grid.

The law also allows the UC discretion over the timing, generation, and resource mix in getting to the least cost path of compliance. If the UC found it necessary, it could delay the achievement of the CO2 reduction goal by up to two years — or it could delay it further if the UC “authorizes construction of a nuclear facility or wind energy facility that would require additional time for completion.” New nuclear would be a much less expensive way of reducing CO2 emissions than most other generation, especially factoring in grid impacts.

Under the law’s performance-based regulation, strict attention and high weighting must be given to protecting customers from being “unreasonably harmed” and “unreasonably” subject to “rate shock” (with great sensitivity given to detecting unreasonability) and to “reduc[ing] low-income energy burdens.”

Regarding the new solar contract extensions, strict adherence must be given to uphold the law’s requirement of “(i) an immediate reduction in the cost of electricity for all classes of customers of the electric public utilities and (ii) a reduction in the estimated long-term cost of electricity for all classes of customers.” Should solar costs continue to fall while utility consumers pay high, fixed contract rates for up to 15 years, the solar facilities would enjoy years of reaping windfalls at consumers’ expense.