- The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Alabama’s congressional map was a racial gerrymander

- The totality of several racial gerrymandering cases creates a safe harbor between violating the Voting Rights Act and unconstitutionally using race to draw congressional districts

- Since the General Assembly has already shown they can draw VRA-compliant districts without using racial data, the Alabama ruling will have little to no effect on how they draw congressional districts later this year

The United States Supreme Court ruled 5-4 on June 8 in Allen v. Milligan that Alabama’s congressional district violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). The ruling upheld the “Gingles framework” for adjudicating racial gerrymandering claims but explicitly rejected any notion that the VRA requires racial proportionality. That balancing of factors means that the ruling will likely have little or no impact on North Carolina’s congressional districts and little or no effect on its state legislative districts.

What Was the Supreme Court’s Reasoning in Allen v. Milligan?

The ruling affirms that the VRA can be used to overturn redistricting plans that have a discriminatory effect and that plaintiffs do not have to prove that defendants intended to discriminate when drawing districts.

At the heart of the ruling is the so-called Gingles framework for determining claims of Section 2 violations. The court laid out that framework in Thornburg v. Gingles, a 1986 North Carolina redistricting case. The court laid out the Gingles framework on page three of Milligan (cleaned up):

To prove a Section 2 violation under Gingles, plaintiffs must satisfy three “preconditions.” First, the “minority group must be sufficiently large and [geographically] compact to constitute a majority in a reasonably configured district.” Second, “the minority group must be able to show that it is politically cohesive.” And third, “the minority must be able to demonstrate that the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it … to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”

Chief Justice John Roberts, who authored the Milligan decision, wrote that a plaintiff-cited alternative map showed that it was “possible that the State’s map has a disparate effect on account of race,” satisfying the first precondition. The court then found that the “polarized voting preferences” and Alabama’s “frequency of racially discriminatory actions” met the other two.

Allen v. Milligan Does Not Require Proportionality by Race, and Another Ruling Prohibits It

The court noted that lawyers for Alabama argued that “the Gingles framework ends up requiring racial proportionality in districting.”

Requiring racial proportionality would be a direct violation of Section 2, Subsection (b) of the VRA:

The extent to which members of a protected class have been elected to office in the State or political subdivision is one circumstance which may be considered: Provided, That [sic] nothing in this section establishes a right to have members of a protected class elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the population.

(Note that the protected class here is “race,” not “Black.” There has been at least one case of the VRA being successfully used against a Black official for violating the voting rights of White citizens.)

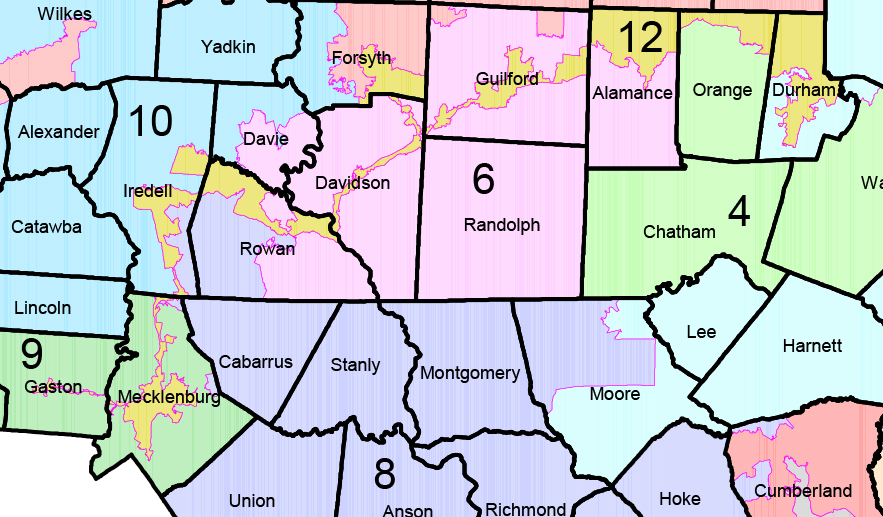

North Carolina’s 12th Congressional District, drawn in 1992, was struck down by the United States Supreme Court in Shaw v. Reno. Graphic source: North Carolina General Assembly.

Chief Justice Roberts countered that the “Gingles framework itself imposes meaningful constraints on proportionality.” He cited Shaw v. Reno, a 1993 case involving North Carolina’s 12th Congressional District, which infamously snaked from Durham through Charlotte and on to Gastonia. Quoting Shaw, Roberts noted that North Carolina had violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment in pursuit of fulfilling the VRA by adding a second majority-Black district:

North Carolina had “concentrated a dispersed minority population in a single district by disregarding traditional districting principles such as compactness, contiguity, and respect for political subdivisions” [Emphasis added.]

In sum, Allen v. Milligan and Shaw v. Reno combine to create brackets between violating the VRA’s protection of people having an equal chance to elect representatives of their choice regardless of race and the 14th Amendment’s prohibition of using race as the predominant factor in drawing districts. States within those brackets will find their districts safe from litigious claims of racial gerrymandering.

How Will Allen v. Milligan Affect this Year’s Redistricting in North Carolina?

So how can the General Assembly find a safe harbor between Allen v. Milligan and Shaw v. Reno?

Chief Justice Roberts noted when he quoted from Shaw that states can find that safe harbor by respecting “traditional districting principles such as compactness, contiguity, and respect for political subdivisions” (something that legislators should do anyhow).

North Carolina has already demonstrated that legislators don’t need to use racial data to comply with the voting rights act when redistricting. They can draw enough VRA-compliant districts without resorting to intentionally drawing districts based on race. Using racial data would be a trap because it would make it difficult for the legislature to prove that race was not the predominant factor when drawing districts if asked in a lawsuit what they did with those data.

Legislators’ ability to draw VRA-compliant districts without resorting to racial data is aided by a relative lack of racially polarized voting by Whites in North Carolina. While North Carolina is a Republican-leaning state, Democrats have won a little over a third of all statewide races over the past decade. Whites comprise 65.1% of the state’s electorate, while Blacks make up only 20.1%. If Whites voted sufficiently as a bloc in consistently defeating Blacks’ preferred candidates (who tend to be Democrats in general elections), North Carolina would be the virtual one-party Republican state Alabama has become.

We should therefore expect that Allen v. Milligan will have little to no impact on North Carolina’s congressional districts when the General Assembly redraws them later this year. The only possible exception is Rep. Don Davis’ 1st Congressional District in the northeastern part of the state. The Cook Political Report changed its rating for the district from toss-up to lean Democratic in anticipation of the General Assembly keeping more Black voters in his district.

Like much of rural North Carolina, however, Davis’ district is trending to the right and will likely lean Republican by the decade’s end. The only way to avert that trend would be to add urban Durham County to the district, but doing so would involve ignoring traditional districting principles, the very behavior that caused the Supreme Court to overturn North Carolina’s congressional map in Shaw v. Reno.

In short, we should expect Allen v. Milligan’s impact on North Carolina congressional districts to be minimal.