Rich Lowry of National Review Online explains why Columbia protesters might see unanticipated consequences from their actions.

“Let’s finish what they did in 1968,” a Columbia protester said the other day.

In political terms, that would mean electing Donald Trump.

The disorder of 1968 — when LBJ declined to run again and Hubert Humphrey, Richard Nixon, and George Wallace faced off — played right into the hands of Nixon, who rode his opposition to the riots and campus unrest into the White House.

As Luke Nichter writes in his book on the 1968 campaign, The Year That Broke Politics, “the great debate of the campaign, the issue that consistently struck the nation’s nerve, and where there were the greatest differences among the three candidates, was law and order.”

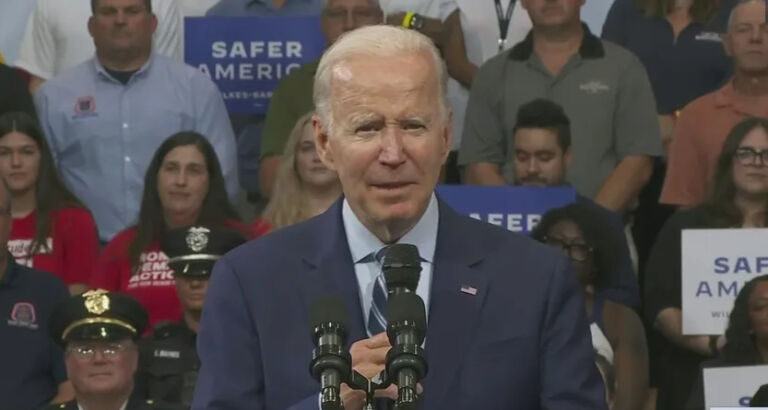

That’s not going to be true this year, when other issues loom much larger than do the student protests. But if “law and order” is broadly conceived to include the chaos at the border (as well as conflict abroad), it is a major theme of 2024 and has inarguably undermined Biden’s presidency. In sheer magnitude, the mayhem of 1968 was much larger and more consequential than anything that is happening today. After the Martin Luther King Jr. assassination, as Nichter notes, more than 50,000 federal and National Guard troops were called out “in one of the largest peacetime deployments on American soil in history.” The rioting rumbled on for a week in Washington, and LBJ later wrote of his “sick feeling” as he watched smoke fill the D.C. sky.

Nixon also went out of his way to position himself as the statesmanlike centrist, which is never Trump’s impulse and rarely his tone.

Nichter explains that Humphrey sought to differentiate himself from Johnson to appeal to liberals, while Wallace ran to Nixon’s right. This ceded the center to Nixon.