- North Carolina’s asset forfeiture regime includes provisions that protect innocent property owners and discourage abuse

- The federal equitable sharing program allows North Carolina law enforcement agencies to circumvent those provisions

- Other states have placed restrictions on the use of equitable sharing; North Carolina should follow their example

Note: This “Freedom Focus” piece incorporates a presentation given on January 13, 2024, to the Mecklenburg County Libertarian Convention by the author.

Civil asset forfeiture is a legal process for confiscating property suspected of having been used for, or derived from, criminal activity. By modern legal standards, it’s distinctly odd. It’s not a criminal proceeding in which the government charges a person with a crime. It’s not a conventional civil proceeding in which one person or organization sues another person or organization. Instead, it’s a civil proceeding in which the government sues an inanimate piece of property.

Civil asset forfeiture was revived by federal government in the 1970s as a novel weapon in the war on drugs. Prior to that, however, it was regarded as an archaic relic—something comparable to putting animals on trial for murder.

One of the last instances of such a trial took place in France in 1457. The defendants, a sow and her piglets, were accused of trampling and killing a child. According to one account of the trial, the sow was convicted and hanged. Her piglets, however, were acquitted “partly because of their youth and innocence and the fact that their mother had set them a bad example, but chiefly because proof of their complicity was not forthcoming.”

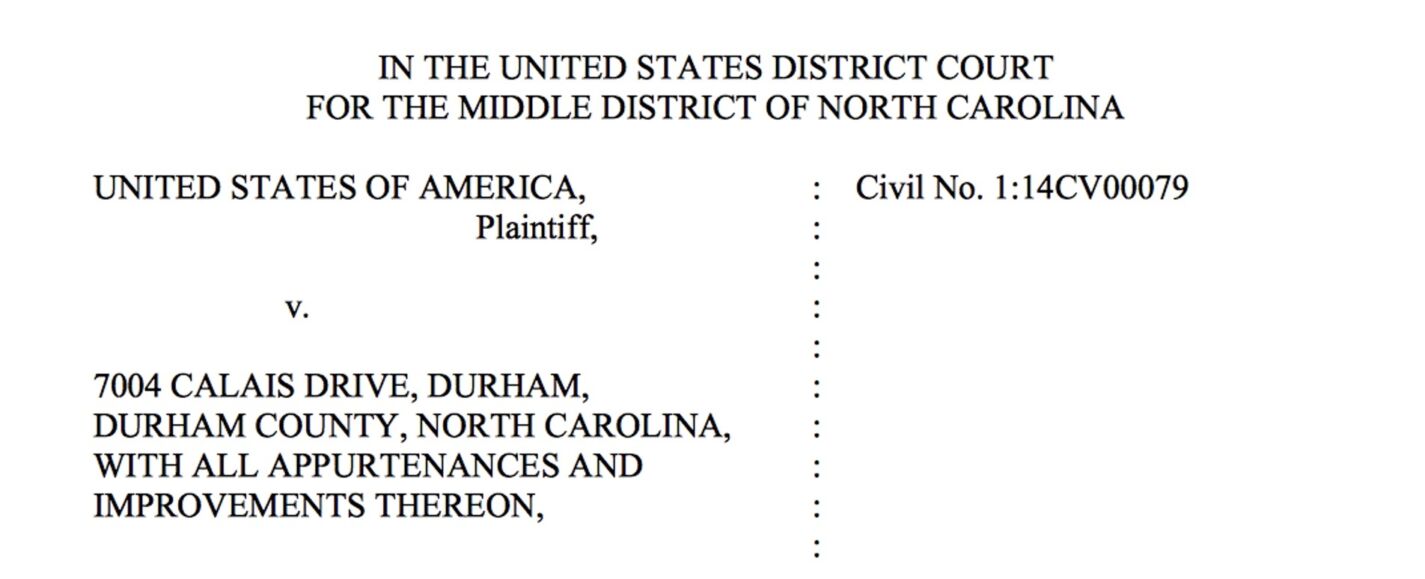

Today we think that is funny. We don’t charge animals with crimes anymore. But it illustrates an important point. In a modern, enlightened legal system, we shouldn’t be filing lawsuits against inanimate objects either, but we do. Every year the federal government files thousands of lawsuits against inanimate objects, including cars, bags of money, and houses. Here’s a real-life example from 2014:

The feds seized this house in Durham after the owner’s grown son, a suspected drug dealer, had moved back in with her. The house, they claimed, was complicit in the son’s activities. The owner eventually recovered her home, but as her attorney explained, that doesn’t mean that justice was done:

Mary Ford had no clue what her son was up to in that house. She got it back, but she had to pay me to do it. It cost her some money, and that’s unfortunate. The government shouldn’t have seized it in the first place. They should have investigated. But they seize first and ask questions later.

Civil asset forfeiture is inherently unjust. Because the property itself is the defendant, there is no need to convict the owner of the underlying crime. Indeed, the owner does not even need to be charged. And because it is a civil rather than a criminal action, the link between the property and the crime does not need to be proved beyond a reasonable doubt; a “preponderance of the evidence” is sufficient. Those aren’t the only problems with the practice, however. The worst thing about civil asset forfeiture is that it perverts the proper relationship between the police and the public by turning the former into predators and the latter into their prey.

The worst thing about civil asset forfeiture is that it perverts the proper relationship between the police and the public by turning the former into predators and the latter into their prey.

The bad news is that these defects didn’t stop the federal government from massively expanding its use of civil asset forfeiture during the last two decades of the 20th century, and they didn’t stop most states following suit by enacting and applying civil asset forfeiture laws of their own. The good news is that North Carolina didn’t go along with that national trend.

North Carolina’s Asset Forfeiture Laws Protect the Innocent and Discourage Abuse

Depriving criminals of their ill-gotten gains is clearly desirable. The challenge is to do it in a way that protects the rights of innocent property owners and discourages abuse by law enforcement agencies. North Carolina’s asset forfeiture regime successfully meets that challenge in two ways.

North Carolina’s Criminal Forfeiture Statutes Protect the Innocent

First, with a couple of minor exceptions, North Carolina doesn’t practice civil asset forfeiture at all. Instead, under our criminal asset forfeiture statutes, property may be forfeited only if the state can prove it was acquired by committing a felony, and only after the owner has been convicted of that felony. Those provisions protect the rights of innocent property owners.

North Carolina’s Constitution Discourages Abuse

Second, under the North Carolina State Constitution, forfeiture proceeds must be used exclusively for maintaining public schools. This removes the incentive for asset forfeiture abuse and discourages the kind of predatory policing that has poisoned relations between the police and the public in many parts of the country.

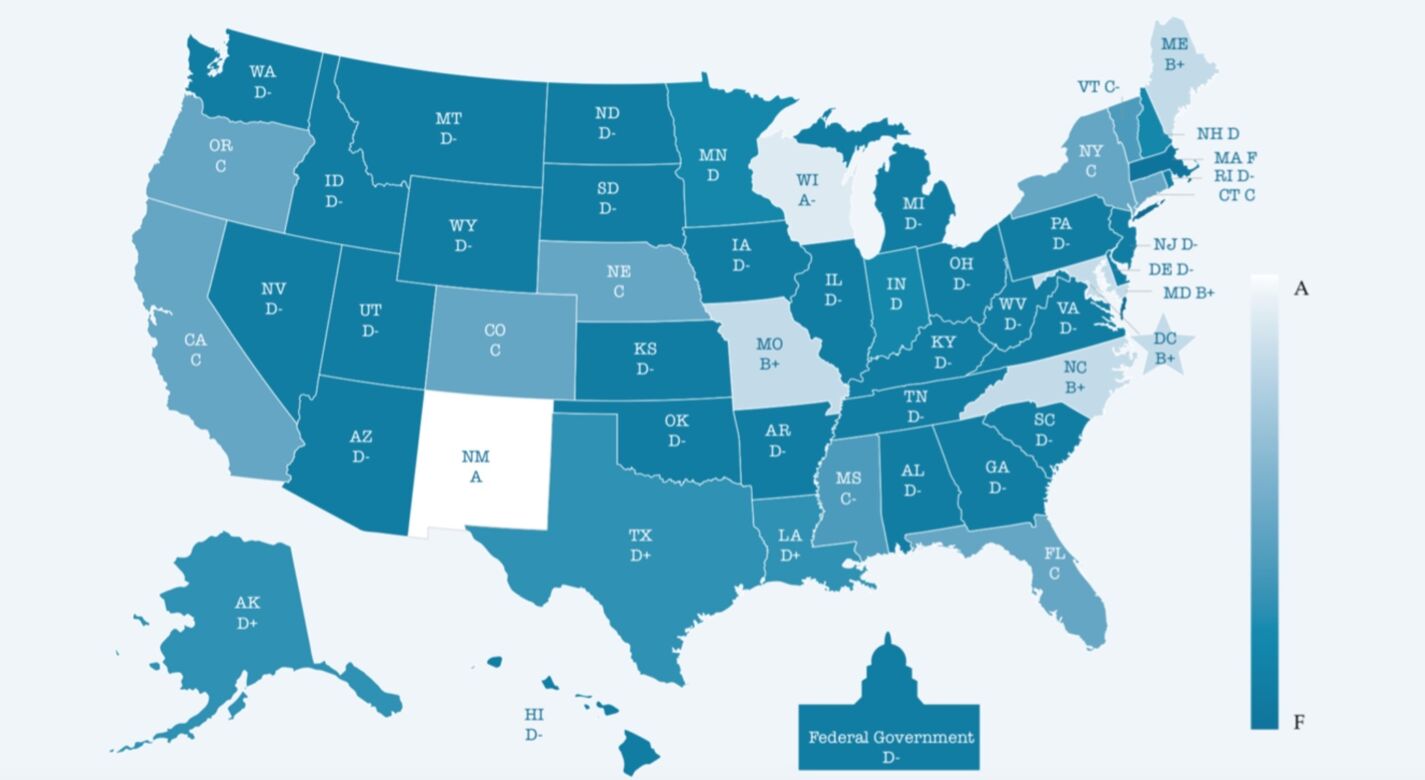

These two provisions of North Carolina’s law have elicited high praise from public policy experts. Indeed, for many years our criminal forfeiture regime was considered the best in the country. In recent years, however, North Carolina has slipped a bit in the rankings.

State Asset Forfeiture Laws as Graded by the Institute for Justice

Source: Institute for Justice

The states that have surpassed us have all reformed their own forfeiture regimes, often using North Carolina as a model, and they’ve also done something else that we have yet to do. They’ve enacted laws that curb the use of a federal program called “equitable sharing.”

The Federal Government’s Equitable Sharing Program Allows North Carolina Law Enforcement Agencies to Circumvent State Law

As the seizure of Mary Hall’s house illustrates, the federal government’s approach to asset forfeiture is very different from North Carolina’s. Because the lawsuit is filed against the property itself, there’s no need to convict — or even charge — the owner of the property. And, making matters worse, under federal asset forfeiture law, law enforcement agencies are not merely allowed to keep and use forfeiture proceeds, they’re required to do so.

It would be bad enough if federal civil asset forfeiture laws were limited to federal law enforcement agencies, but unfortunately they’re not. Instead, a federal program called “equitable sharing” makes it possible for state and local agencies to seize assets, refer them to federal agencies for processing by federal courts, and receive a substantial portion of the proceeds in return. Because the transaction takes place under federal law, state law does not apply, and that’s the source of the problem. Simply put, federal equitable sharing makes it possible for state and local law enforcement agencies to circumvent any protective provisions that may be present under state law.

Simply put, federal equitable sharing makes it possible for state and local law enforcement agencies to circumvent any protective provisions that may be present under state law.

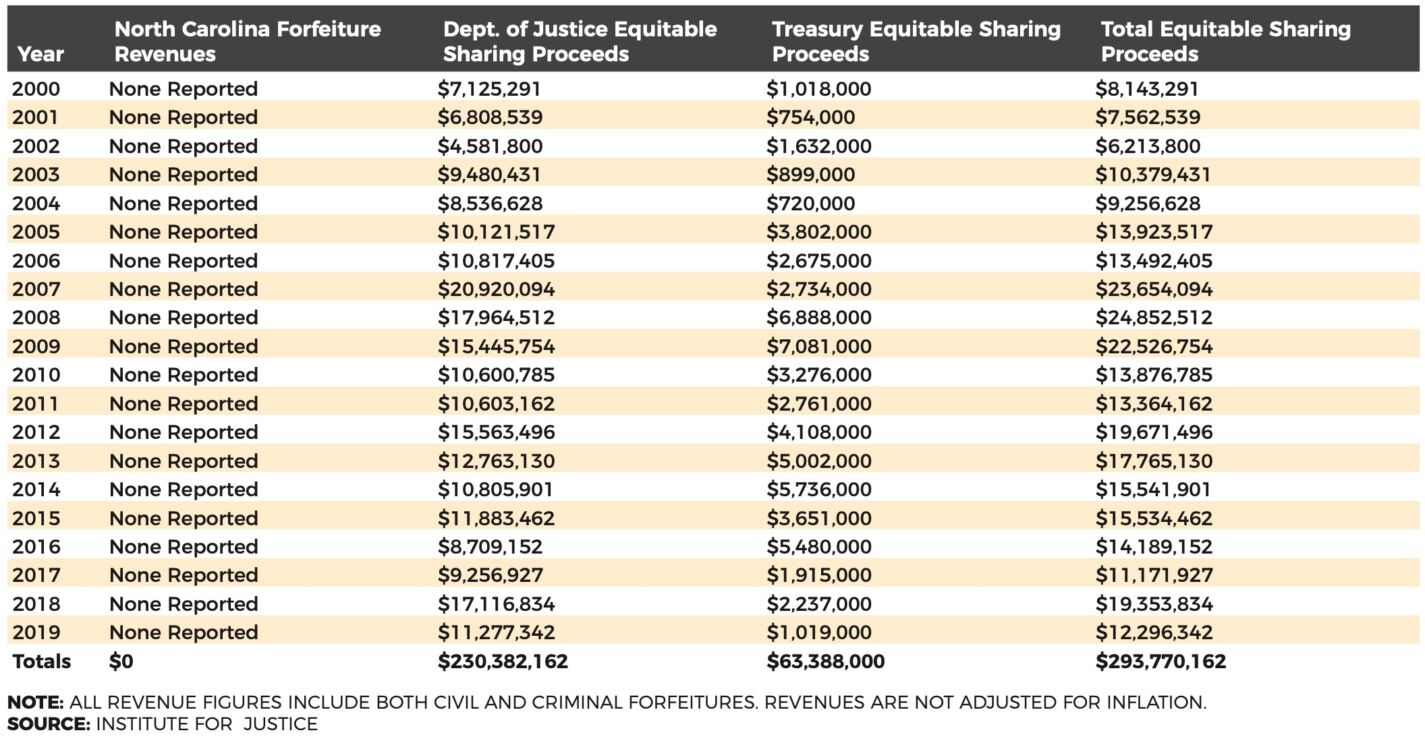

In North Carolina more than 100 agencies, including the State Bureau of Investigation and the Highway Patrol, regularly process seized assets through the equitable sharing program. Between 2000 and 2019, those agencies were the beneficiaries of almost $300 million worth equitable sharing proceeds.

Total Equitable Sharing Proceeds In North Carolina, 2000 to 2019

On a per-capita basis, that’s much worse than most states, which is why North Carolina invariably ends up near the bottom of the list when the Institute for Justice rates the states in terms of equitable sharing.

Two Forms of Equitable Sharing

There are two different ways in which state and local agencies can use equitable sharing to circumvent state asset forfeiture laws. The first is by referring seized assets to a federal agency for “adoption.” After processing the assets through the federal system, the adopting agency returns the bulk of the proceeds to the state or local agency that made the seizure. It’s really just a money-laundering scheme, and of course the launderer gets a cut, generally 20 percent.

The second way in which state and local agencies can use equitable sharing to circumvent state asset forfeiture laws is to participate with a federal agency in a “joint investigation.” With joint investigations, local law enforcement’s share is determined by their level of participation, but the feds always keep at least 20 percent.

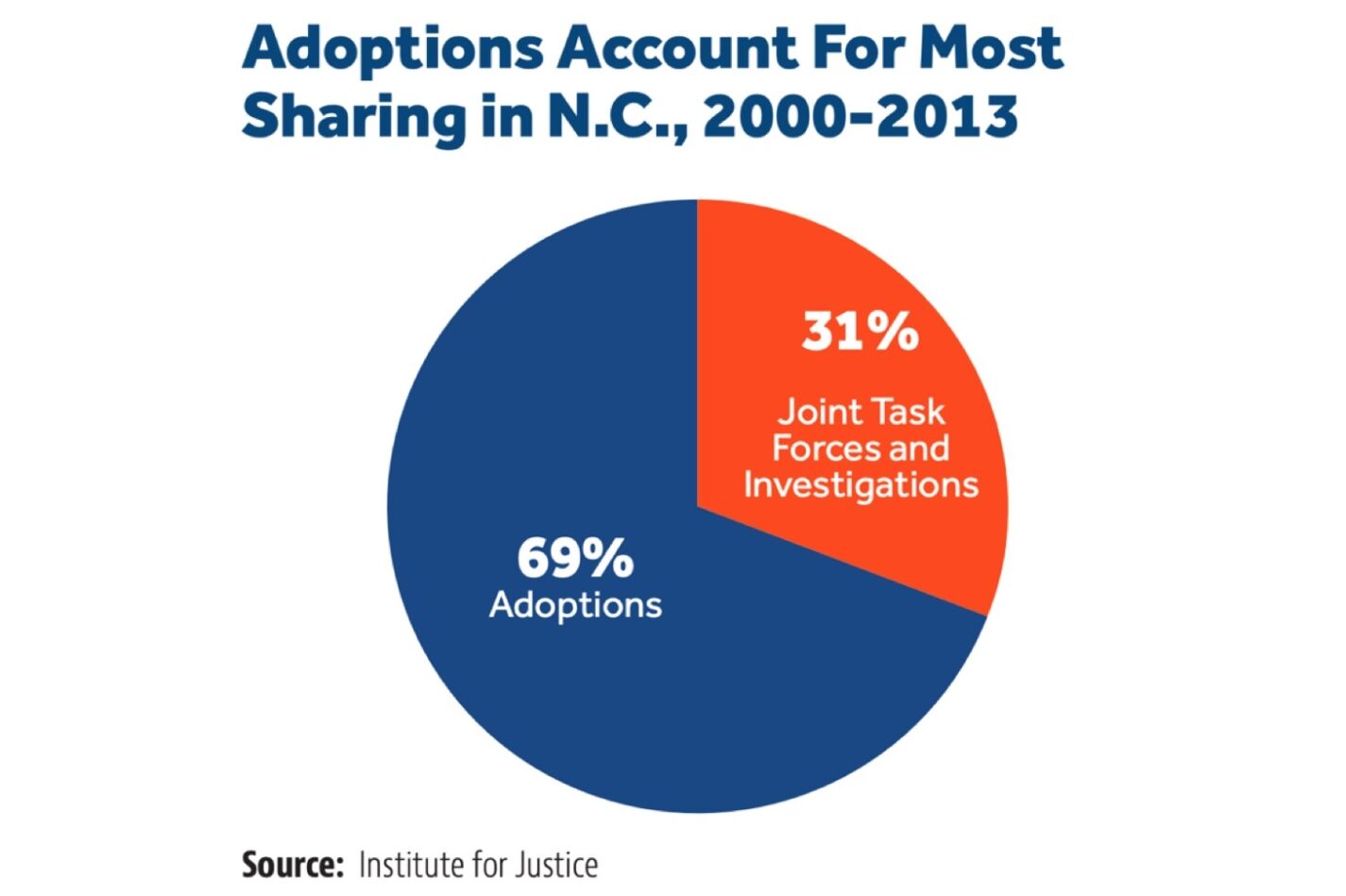

Adoptions and joint investigations both make it possible for state and local law enforcement agencies to circumvent state asset forfeiture laws, and they both make it possible for state and local agencies to keep forfeiture proceeds and use them for their own purposes. Nevertheless, there are important differences. Joint investigations can play a legitimate and valuable role in law enforcement. They facilitate the sharing of information, expertise, and resources, and they often lead to the arrest and conviction of dangerous criminals. Adoptions, on the other hand, serve only one purpose: to provide a way for state and local law enforcement agencies to circumvent state asset forfeiture laws. Which makes it particularly galling that adoptions account for most of the equitable sharing in North Carolina.

What Other States Have Done to Prevent or Minimize Circumvention

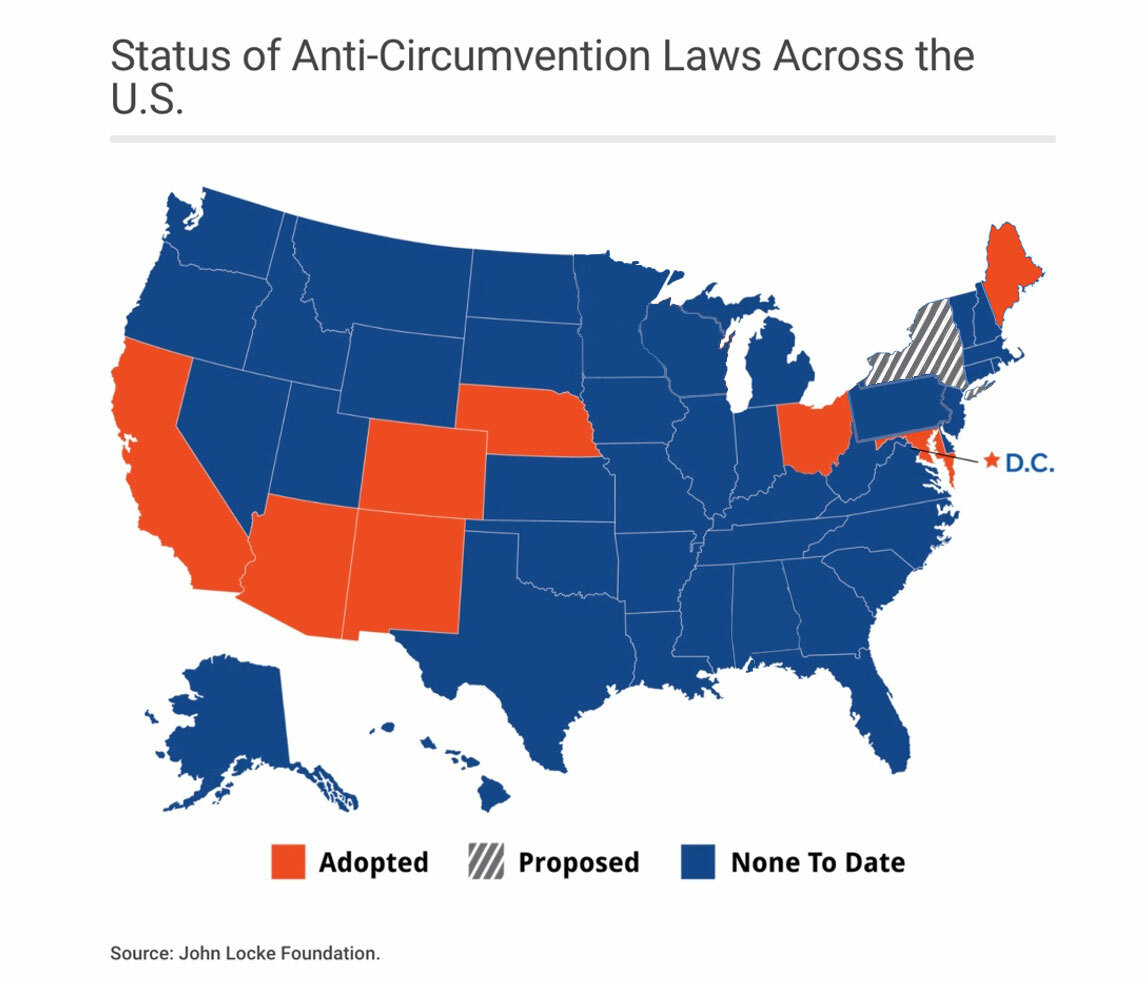

Anti-circumvention legislation has been enacted in eight states and the District of Columbia.

Significantly, despite equitable sharing’s manifest faults, states have been reluctant to ban the practice completely, and indeed no state has done so. This, no doubt, is mostly because the prospect of taking money from drug traffickers and other criminals and using it to fund law enforcement is almost irresistibly attractive to legislators. However, it is also because no one wants to stop participating in joint investigations, which as previously noted can play a valuable role in law enforcement. Rather than banning equitable sharing entirely, therefore, reformers have experimented with various ways of mitigating its worst aspects without entirely cutting off the flow of shared revenue and without losing the benefits of joint investigations. From their experience, we can draw three broad lessons about what works and what doesn’t.

Lesson One: Ban or severely restrict federal adoptions.

The District of Columbia was the first jurisdiction in the country to enact anti-circumvention legislation. In addition to reforming the district’s own asset forfeiture regime, the Civil Asset Forfeiture Amendment Act of 2014 included two anti-circumvention provisions, one of which was an outright ban on federal adoptions. In 2016, California passed an asset forfeiture bill that included a provision that effectively banned adoptions within the state. In 2017, Pennsylvania followed suit with a similar measure. That same year, the Institute for Justice incorporated a modified adoption ban into its Anti-Circumvention Model Act. Other asset forfeiture reform bills that have been introduced since then have included a similar provision.

In short, banning or severely restricting federal adoptions has become a generally recognized as a “best practice” when it comes to asset forfeiture reform.

Lesson Two: Do not divert equitable sharing proceeds away from law enforcement.

The ban of federal adoptions wasn’t the only anti-circumvention provision included in the District of Columbia’s 2014 Civil Asset Forfeiture Amendment Act. While the Act did not restrict the district’s law enforcement agencies’ ability to participate in joint investigations with federal agencies, it did restrict the use of shared proceeds derived from such investigations by requiring that all such proceeds be deposited in the General Fund.

In theory, diverting forfeiture proceeds from law enforcement to the General Fund would appear to be a very sensible restriction to impose. Like the provision in North Carolina’s constitution requiring that forfeiture proceeds must be used for public education, diverting proceeds to the General Fund removes the profit motive from the forfeiture process and ensures that it is used — not to generate revenue — but for its proper purpose, which is to punish criminals and discourage crime.

In practice, however, there was a problem with the diversionary approach. The problem was not immediately apparent, because the District of Columbia’s reform act did not become effective at the time of passage, but it was recognized the following year when New Mexico enacted asset forfeiture legislation that also diverted forfeiture assets to the general fund.

New Mexico’s law took immediate effect, and when it did, the federal government’s reaction was swift and brutal. Citing its own rule requiring that equitable sharing funds must be used “by law enforcement agencies for law enforcement purposes only,” the Department of Justice (DOJ) punished New Mexico by announcing that it would no longer participate in any joint investigations with the state’s law enforcement agencies. It was an extreme response. The DOJ could have continued to participate in joint operations and simply stopped sharing the proceeds of assets seized in the course of those operations, but it evidently wanted to send a message, and that message was received. None of the anti-circumvention laws that have passed since 2015 have included a provision that diverts forfeiture proceeds away from law enforcement, nor is there any such provision in IJ’s Model Act.

Lesson Three: Permit equitable sharing only when the value of seized assets exceeds a minimum monetary threshold.

With the diversionary approach effectively off the table, reformers were forced to look for an alternative way of taking the profit motive out of the forfeiture process. In the end, they settled for an approach that takes the profit motive out of most forfeiture cases by limiting equitable sharing to cases in which the value of seized assets exceeds a minimum monetary threshold, generally starting around $50,000 to $100,000.

As “second-best” solutions go, this one is not too bad. Because most forfeiture cases involve small seizure amounts, the imposition of a threshold ensures that most forfeiture decisions will be made on public safety grounds alone. At the same time, because most forfeiture revenue comes from cases involving large seizure amounts, the imposition of a threshold accomplishes this goal with a minimal loss of shared revenue.

The John Locke Foundation has added asset forfeiture reform to our legislative agenda. We hope to convince the North Carolina General Assembly to enact anti-circumvention legislation along the lines described above. Doing so would return North Carolina to its proper place as the state with the best asset forfeiture regime in the country.