The General Assembly passed Senate Bill 747 over Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto last October. It delivered a host of election reforms, many of which the John Locke Foundation had advocated for. Those reforms were first implemented in the March 5 primary.

In addition, vote ID, which voters approved in 2018, cleared legal hurdles and was finally implemented for the 2023 municipal elections. The March 5 primary was the first statewide election with voter ID.

How did those reforms perform? To answer that question, we looked at data pulled from the North Carolina State Board of Elections (SBE) and Locke’s Vote Tracker website (which also pulls data from the SBE).

We will focus on three reforms:

- Voter ID

- Making election day the deadline for regular mail ballots (it had been three days after election day).

- Not counting ballots from same-day registration that could not be verified.

Voter ID

While the National Conference of State Legislatures lists North Carolina as a strict voter ID state, our ID law is actually very soft and made softer still by SBE regulations.

People presenting themselves to vote without a voter ID must cast a provisional ballot. The ballot will be counted if the person later presents an ID to county election officials. The person can also complete a reasonable impediment form that gives an exhaustive list of reasons for not having an ID. Provisional ballots accompanied by a reasonable impediment form will be counted unless the county board of elections unanimously decides that the form is false.

Of the 409 ballots not counted due to both lacking voter ID and not completing a reasonable impediment form, 150 were Republicans with 147 Democrats, 111 unaffiliated voters, and one Libertarian.

In total, 1,185 provisional ballots were cast due to voter ID. Of those, 683 were eventually accepted in full, with ten more partially accepted (for example, counted for statewide elections but not for districts where the voter no longer lives).

The SBE listed 469 ballots as not being counted due to not having voter ID. Most of those, 409, were due to the people not filing a reasonable impediment form. Effectively, this means they presented no reason why they didn’t show an ID or did not provide one to the SBE at a later date for their ballot to count.

Of the 409 ballots not counted due to both lacking voter ID and not completing a reasonable impediment form, 150 were Republicans with 147 Democrats, 111 unaffiliated voters, and one Libertarian.

Election Day Deadline for Mail Ballots

North Carolina traditionally required absentee-by-mail ballots to be returned to county election officials by election day. The General Assembly voted in 2009 to change the deadline to three days after election day if election officials believed the ballot was properly postmarked by election day. The result was “confusion, conflict, and ‘postmark games:'”

The 2020 election gave examples of how the three-day postmark exception creates confusion and conflict.

Postmarks are required for ballots that election officials receive after election day because they need to know that those ballots were not mailed after initial election results are known. Sometimes, however, there are problems of ballots received without a postmark or with an illegible postmark. The State Board of Elections instructed county boards receiving ballots without legible postmarks to “conduct research with the USPS or commercial carrier to determine the date it was in the custody of USPS or the commercial carrier” (Numbered Memo 2020-22).

Allowing a three-day delay with a postmark also creates confusion for voters and election boards.

In response, the General Assembly returned the mail ballot deadline to election day in SB 747.

There was a slight uptick in the number of ballots not accepted for being late from 2.9% (800/27,314) in the 2020 primary to 4.0% (1128/28,442) in the 2024 primary. That is a 328-vote difference out of 28,442 mail ballots cast.

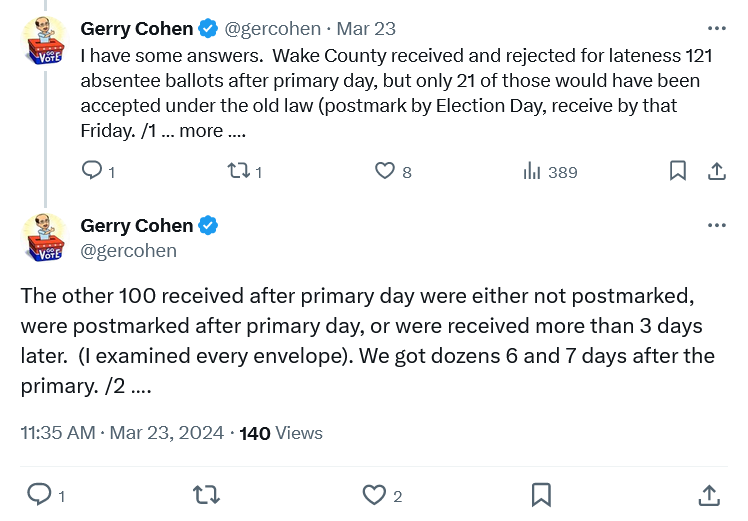

Of course, not all the ballots that came in within three days after election day would have been counted under the old law. For example, a Wake County Board of Elections member reported that most of the ballots they received after election day would not have been counted under either the new or the old rules.

As voters continue to adjust to the new deadline, expect the gap in the number of ballots not counted due to lateness to decline. The General Assembly can help by adjusting the deadline to request an absentee ballot to match the new deadline for submitting the ballot. The John Locke Foundation advocates for that policy solution.

Stopping Ghost Voters: Unverified Same-Day Registrations

Another problem with how elections have been conducted in North Carolina is “ghost voters,” people who register using same-day registration (SDR) during early voting and whose ballot is counted even though election officials cannot verify the registration:

The North Carolina “Notice to Same-Day Registrants” (those who register to vote during early voting) contains the following:

In the event the county board of elections cannot verify your address, your voter registration application will be denied and your absentee vote may be subject to challenge.

Those two sentences describe a situation in which someone registers to vote, claiming to live at a particular address. The county board of elections cannot verify that the person lives at that address, but the board still accepts the ballot from that unverified registration. The only thing that might prevent the ballot from that unverified registration from being counted is that it “may be subject to challenge.”

As we will see below, the threat of a challenge is empty. Nothing in current law or practice requires verification of SDR registrations before the associated ballots are counted.

There were about 1,700 such ghost voters in the 2020 general election. Our research found that “the unverified rate for SDRs (1.82%) is almost twice as high as the unverified rate for non-SDR new registrations (0.95%). That finding is consistent with the results of [a] 2008 Civitas Institute study”.

SB 747 addressed that problem by requiring same-day registrations to be verified before the accompanying ballots are counted.

So, how many ballots from unverified registrations were not counted due to the new law?

Since there were 1,760 unverified same-day registrations in the 2020 general election (turnout: 5,545,848), we would expect to see several hundred unverified same-day registrations in the 2024 primary (turnout: 1,790,838).

That was not the case. According to data in the SBE’s “absentee_20240305.zip” file, there were only 36 ballots designated “SDR-FAILED VERIFICATION.”

While it may be some time before we know all the reasons for the discrepancy, this is an early sign that the law is doing its job of discouraging people who are not legally qualified to vote in North Carolina from using SDR to cast a ballot illegally.

The March 5 primary was the first test of several election reforms. Data from that primary indicates that those reforms are functioning as intended without unduly burdening voters.