- After a decade of resistance, North Carolina expanded its Medicaid program this year

- It marks the largest entitlement increase in state history

- Since government intervention is the major culprit in making health care unaffordable, a better recipe would be to remove — not expand — government interference in health care

On December 1, up to 600,000 more North Carolinians became eligible for Medicaid, the largest government entitlement increase in state history. If all the newly eligible sign up, roughly 3.5 million Tar Heels will be enrolled in the program, up from about 1.5 million just a decade ago.

With the increase, about one in three North Carolinians would be dependent on this government program to pay for their medical care, joining another 2.1 million reliant upon the government via Medicare.

Such a massive government dependency for something so critically important marks a stunning drift away from a free society toward one of subjects depending upon the whims of politicians and bureaucrats for coverage and care.

Rather than expanding government dependency and in turn expanding government control over greater swaths of our lives, a better recipe would be to unwind the interventions causing the problems in the health care industry in the first place.

There are a multitude of government regulations, interventions, and controls forcing health care costs to become unaffordable to far too many North Carolinians — and Americans. Below is a list of the most damaging factors:

Third-Party Payer System Inflates Demand, Encourages More Unnecessary Care

Patients actually pay relatively little of the costs of their health care. According to the American Medical Association, only 10 percent of health care expenditures in 2021 were direct, out-of-pocket payments from patients. Nearly 40 percent were paid via Medicaid and Medicare.

It wasn’t always this way. Third-party payments have been increasing substantially over the past several decades. According to this 2015 analysis by economist Mark Perry, “almost half (47%) of health care expenditures in 1960 were paid by consumers out-of-pocket, and by 1990 that share had fallen to 20% and by 2009 to only 12%.”

The growth of government programs Medicaid and Medicare are large culprits in this shift. Moreover, federal and state laws mandate many services and providers be covered under private health insurance plans, which shifts more medical costs for those patients off the patient and onto the insurance companies.

Such a heavy reliance on third-party payments insulates patients from the true costs of the health care they consume. The result is often an overconsumption of care and a lack of consideration of cost in care decisions. Very little price shopping occurs in health care.

It also makes patients and doctors more likely to take a “kitchen sink” approach to testing, diagnosis, and treatment, since there are few immediate consequences for doing so. Someone else is paying the bill, so why not? And because doctors are largely paid on a fee-for-service basis, they have the incentive to oblige.

Many of these procedures are unnecessary, driving up health care costs significantly. This 2017 study published by the National Library of Medicine found physicians self-reported that a “median of 20.6% of overall medical care was unnecessary, including 22.0% of prescription medications, 24.9% of tests, and 11.1% of procedures.”

More recent data are difficult to come by, but a 2012 study by the Institute of Medicine estimated the cost of unnecessary care at more than $200 billion, a figure that’s sure to be significantly higher today. For instance, hospital and physician services, along with prescription drugs, combined to more than $2.3 trillion in spending in 2021. If 20 percent of those expenditures were unneeded, the amount spent on unnecessary care would be more than $460 billion.

Government Intervention Means Administrative Bloat

Milton Friedman once said, “in a bureaucratic system, useless work drives out useful work.” The result is a proliferation of bureaucrats and administrators, and with government intervention having such a heavy hand, America’s health care system provides a perfect example of Friedman’s observation.

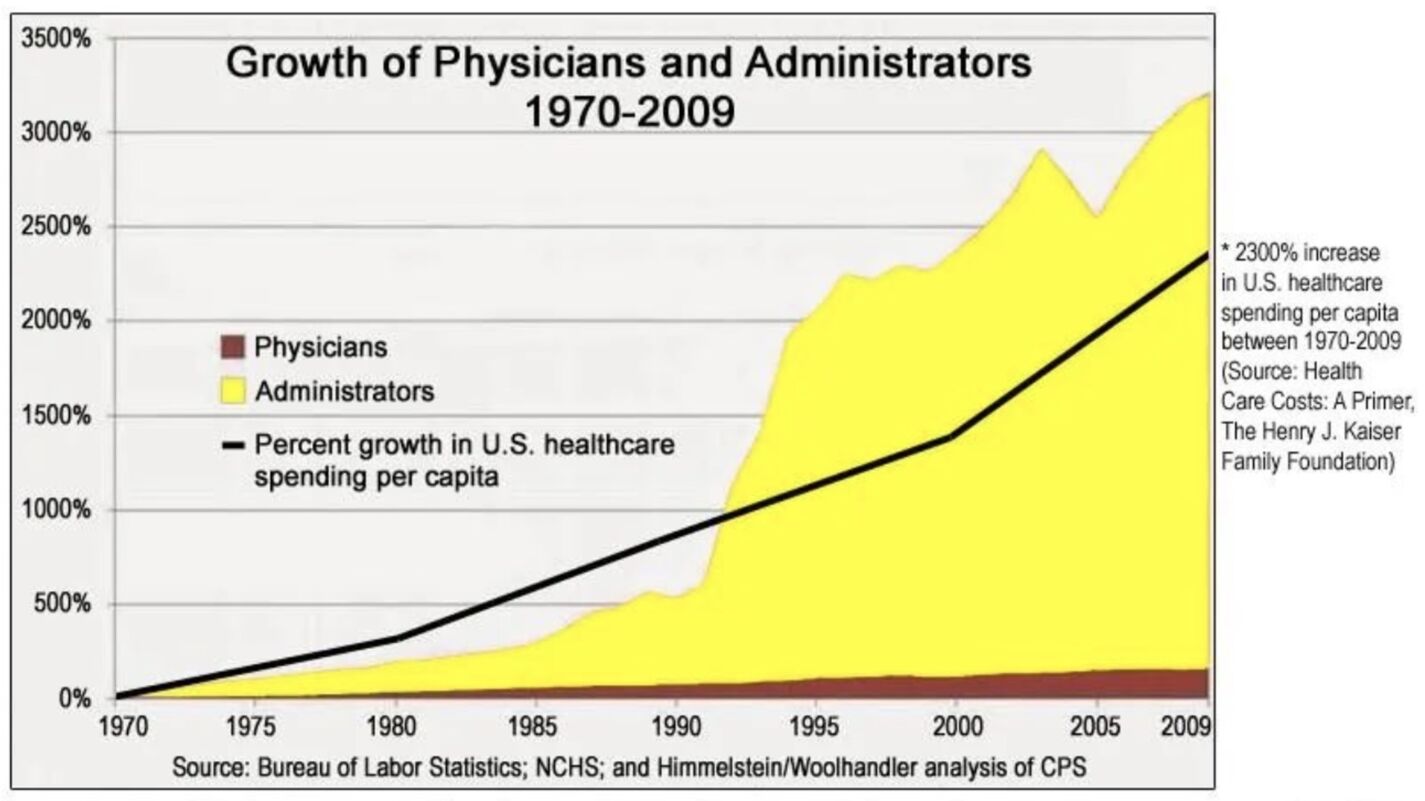

Unsurprisingly, the number of health care administrators has exploded over the past five decades.

Unsurprisingly, the number of health care administrators has exploded over the past five decades, especially so in the last three, compared to the increase in physicians (see chart below). While per-capita health care spending rose by 2,300 percent, the number of administrators grew by more than 3,000 percent. Rapidly growing compliance costs courtesy of Obamacare (see below) no doubt has continued — if not worsened — this trend.

Government Intervention Leading to Hospital Consolidation

Consolidation of hospitals and medical providers is a trend that has been rapidly increasing over the past several years.

University of Pennsylvania health economist David Grande noted recently, “There were 1,887 hospital mergers announced between 1998 through the end of 2021, according to the American Hospital Association. Those mergers reduced the number of hospitals from about 8,000 down to around just over 6,000.”

Grande further indicated that such consolidation will “reduce access to healthcare,” especially for low-income populations, as well as result in “higher prices.”

Main drivers of consolidation include the high compliance costs required to follow heavy government regulation — costs larger firms can more easily absorb — and higher reimbursement rates for procedures conducted in hospital systems compared with independent practices.

Consolidation had been trending up for decades, but the passage of Obamacare heightened the trend, in no small part due it exacerbating the problems associated with government intervention.

Indeed, consolidation was one of the intended outcomes of the 2009 act. “Obamacare’s architects thought hospital consolidation would streamline care, improve the quality of medical services, and generate savings for patients,” noted this 2019 Forbes article. “Obamacare encouraged consolidation by incentivizing providers to coordinate care and adjusting Medicare payments to make mergers a smarter financial option.” The result instead has been higher costs and less access.

Government Interventions Restrict Supply

There are many ways that government interventions restrict the supply of medical care, which also helps to drive up costs.

In North Carolina, the most obvious culprit is the state’s Certificate of Need (CON) law. CON laws require that health care providers get government approval to operate or expand certain services. North Carolina is one of 35 states that have such laws, and despite some modest rollbacks in this year’s budget, our state has one of the strictest CON regimes in the nation.

Government intervention in the health care industry has been a disaster, rapidly increasing costs while limiting access.

The majority of research unsurprisingly concludes that CON laws increase health care costs and restrict availability.

Another policy limiting access to care is restrictions on nurses’ scope of practice. In North Carolina, if nurse practitioners want to practice in North Carolina, they must establish a collaborative practice agreement with a physician. Especially with a sizeable physician shortage on the horizon, allowing nurses more leeway to perform basic medical services would go a long way toward providing greater access to care, especially in rural areas.

Then there are the efforts of the American Medical Association to limit the number of licensed doctors. As reported by The American Conservative, “The American Medical Association (AMA) artificially limits the number of doctors, which drives up salaries for doctors and reduces the availability of care.”

For more than a hundred years, the AMA has been successfully lobbying governments to enact laws that would restrict the number of new doctors in the country. AMA activities have included dramatically decreasing the number of medical schools across the U.S. and turning the process of becoming a doctor into a monumental feat that “requires navigating a maze of accrediting, licensing, and examining bodies.”

Conclusion

Government intervention in the health care industry has been a disaster, rapidly increasing costs while limiting access. The antidote is to remove the many layers of government interference, not to expand a government program like Medicaid so that one in three North Carolinians are dependent on it for their health care. Merely eliminating unnecessary care that results largely from the government-orchestrated third-party payer system could reduce health care spending by $460 billion.

Freeing the market, not increasing centralized control, is the best way to address affordability and access problems. In a truly free society, the default method for addressing such concerns would be to expand the free interplay of producers and consumers in the marketplace, not to approve the largest government entitlement in state history.