With North Carolina’s film production tax credits set to expire at the end of this calendar year, the industry is intent on demonstrating that the incentive is worth keeping. Its feature production was just released: a study prepared by Dr. Robert Handfield, a North Carolina State University professor of supply chain management, that generated the incredible finding that

for every dollar of credit issued, the industry generated $9.11 in direct spending and contributed $1.52 in tax revenue back to North Carolina.

Shortly afterward, a memorandum to Rep. Rick Catlin (R-New Hanover) prepared by Patrick McHugh and Barry Boardman of the Fiscal Research Division of the North Carolina General Assembly gave a preliminary review to the new industry study of North Carolina’s film tax credits. The review was scathing.

The Fiscal Research memorandum eviscerated the industry study (emphasis in original):

The Handfield report uses a supply chain methodology that includes interviews, surveys, and payroll data from various sources. While much of the data and methodology used in this report has not been made public, the report incorrectly concludes that the Film Production Credit’s net contribution to the State is positive. FRD concludes that the reported positive return on investment is based on a series of misunderstandings of the State’s tax laws, invalid or overstated assumptions, and errors in accounting.

Our analysis, which corrects for the most obvious errors in the Handfield report, shows that the Film Production Credit creates a negative return on investment. The errors identified in this memo where communicated to Dr. Handfield prior to publication of the report. However, as of this date, no response has been provided. Because some of the methods used in the Handfield report have not been fully vetted, the analysis in this memorandum is preliminary. A better understanding of those methods will only allow us to fine-tune our analysis, but we would not expect our conclusion that the Film Credit does not "pay for itself" to change. In fact, a more detailed report is likely to conclude that the loss to the State is even greater than we present here.

McHugh and Boardman produced the following table "after adjusting for the most serious errors in the report":

They wrote:

As shown above, once the most significant errors in the Handfield report are removed, the return on investment in State revenues falls to less than 50 cents on the dollar. Even when estimated local tax revenues are included, the Film Production Credit results in a net fiscal loss. Typically, when considering the benefit of a State-level tax credit, local tax gains are not included. However, as the Handfield report includes State and local revenues, both perspectives are included here.

McHugh and Boardman discuss several errors in the report, including that it:

- "understates the cost of the Film Credit by almost $24 million"

- "overstates the amount of personal income taxes paid by film production workers"

- "overstates the sales tax revenue generated by purchases made by film productions"

- "significantly overstates the tax revenue generated when film workers spend their earnings"

They also raise questions about the report’s estimation of the average salary of workers, its calculations over income and corporate taxes, and its assumptions of tourism effects.

Still no consideration of opportunity costs

Even though "basic corrections of unsound assumptions and accounting problems make it clear that the Handfield report incorrectly asserts that the Film Production Credit ‘pays for itself’ through increased tax revenue," McHugh and Boardman noted that "our preliminary analysis does not attempt to alter the fundamental approach used in the Handfield report."

As I observed, this approach made no accounting for opportunity costs and assumed all production exists because of the tax credit. So in evaluating it on its own merits, Fiscal Research didn’t do so either, although in its analysis it acknowledged the omission:

It is worth noting that another aspect of measuring the net benefit of a tax credit, beyond a return on investment approach, would be to include opportunity costs of the credit such as higher tax rates or reduced public sector spending. Neither the Handfield report nor our analysis here attempts to weigh those types of trade-offs that would be associated with the Film Credit.

That omission would also negatively affect the returns on the film tax credits. As this newsletter discussed last fall on evaluating such studies,

If a study intends to prove that an incentive is attractive to the favored industry, it will focus just on the direct and subsequent benefits of the industry. The study will rely on an input/output model such as IMPLAN that doesn’t account for opportunity costs and doesn’t require an economist to conduct.

If a study intends to test whether an incentive is good for the overall economy of the state, it will weigh the direct and subsequent industry benefits against the direct and subsequent lost economic activities overall. It will use a cost/benefit framework and will most likely be conducted by an economist.

This distinction is important to keep in mind as state officials await a study of film incentives, to be done, apparently, from a perspective of supply chain management.

Proper analysis of state policy absolutely must take into account costs as well as benefits. State resources should not go into proving the patently obvious, such as that people and businesses like free money. Or, for goodness’ sake, that they prefer to spend free money after getting it.

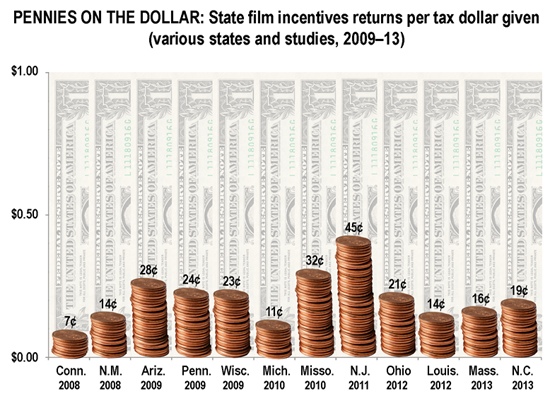

That omission would factor in Fiscal Research’s finding of a 46-cent return on every dollar in credit given. An earlier presentation from the Commerce Dept. yielded a finding of 19 cents on the dollar returned.

As this newsletter’s readers will recall, such a small return — i.e., such a net loss — would be well in keeping with several other states’ studies of their own film tax credit programs:

But wouldn’t North Carolina be out on a limb if its film tax credits expired?

No. As discussed last year, North Carolina would join a growing group of states that have ended or suspended their film tax credits or never joined in the folly to begin with. Many states have opted out, including several quite recently (most recent first):

- Missouri: program sunsetted on Nov. 28, 2013

- Wisconsin: program ended as of July 1, 2013

- Kansas: program ended as of Dec. 31, 2012 — after having been reinstated in 2011 following suspension in 2009-10

- Iowa: program terminated (it had been suspended in 2009 after discovery of widespread fraud and abuse)

- Indiana: program sunsetted in 2012

- Arizona: program sunsetted in 2010

- New Jersey: program slated to sunset in 2015

- Connecticut: program placed on hiatus

- Idaho: program hasn’t received any appropriations since 2010

- The District of Columbia: program not funded

- Delaware: no program

- Nebraska: no program

- New Hampshire: no program

- North Dakota: no program

- South Dakota: no program

In other words, over a quarter of U.S. states are not playing the film incentives games.

Click here for the Rights & Regulation Update archive.

You can unsubscribe to this and all future e-mails from the John Locke Foundation by clicking the "Manage Subscriptions" button at the top of this newsletter.