- Sawmills have been decreasing in North Carolina for over a decade due to regulatory burdens and foreign competition

- Housing continues to be an issue in the state with input costs varying greatly and demand on the rise

- HB 295, the “Support Local Sawmills” Act would allow the direct purchasing of ungraded lumber, which would reduce lumber waste, support small business, and make building homes easier

The Housing Problem

North Carolina finds itself deeply entrenched in the grips of an alarming housing crisis. With the state’s population growing by 9.8% over the last 10 years, North Carolina is expected to be almost one million housing units short by 2030.

Even if housing construction increases, there is no guarantee that those homes will be affordable to the average North Carolinians. An Urban Institute report revealed that not a single county in N.C. possesses an adequate supply of affordable homes to cater to its residents. This problem will only be exacerbated as people continue to move here from higher cost-of-living states, such as New York and California, with their ability to afford more expensive homes helping raise the average market price.

The price of housing is not only influenced by demand pressures, but by material costs. During the Covid pandemic the price of lumber quadrupled and has only just recently begun to return to prior real prices. With high regulatory burdens on local lumber combined with tariffs on imported lumber, however, lumber prices will continue to remain higher than they could be, serving to help prop up already unaffordable housing prices.

The Sawmill Problem

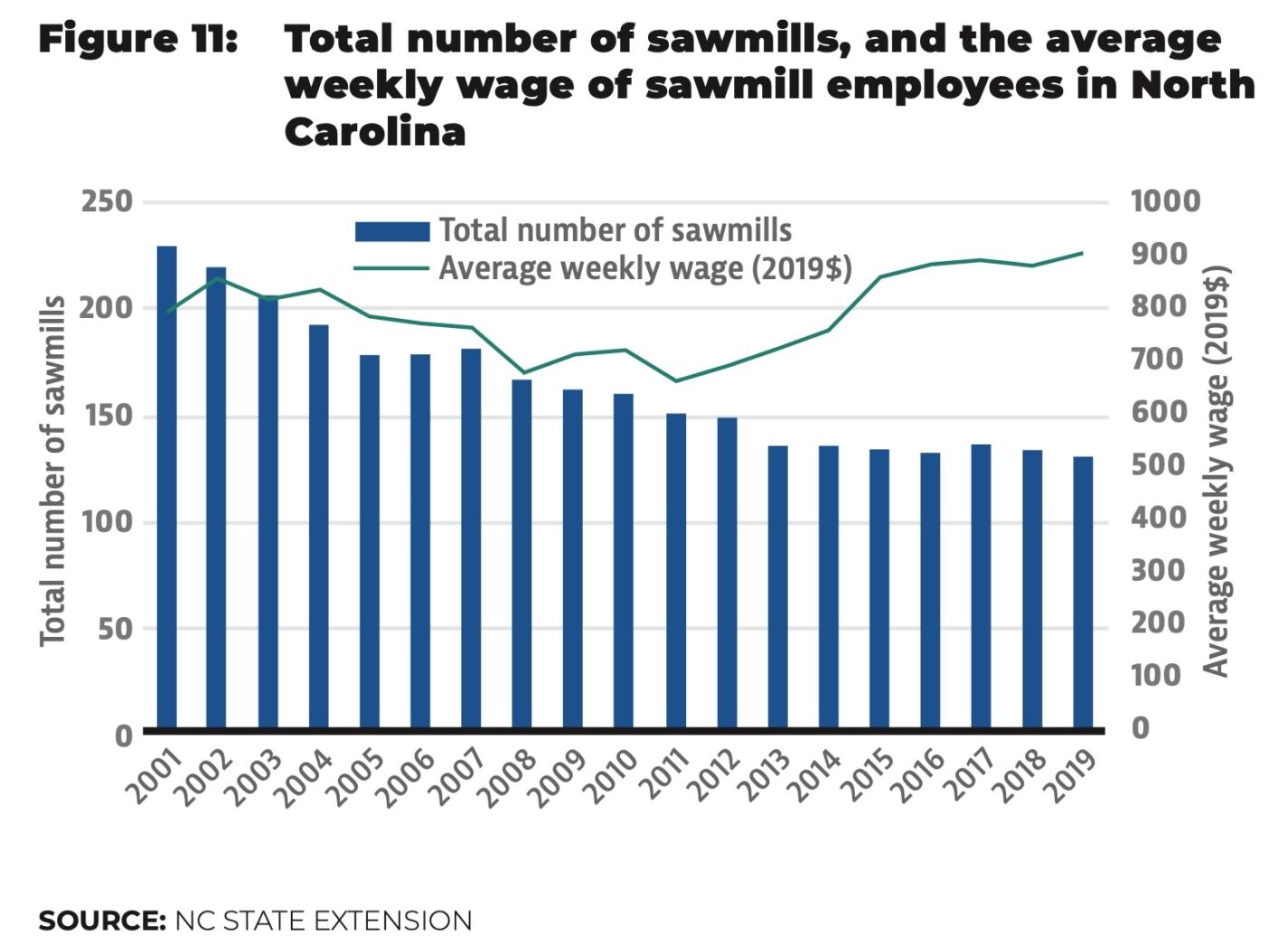

The history and abundance of forests in North Carolina have made forestry an integral part of the state’s economy, as discussed in Locke’s recent report on North Carolina’s model forest management, “First in Forestry.” In 2019 the sector made up around $35 billion. Despite this vast history and the industry’s economic significance, the number of sawmills has been consistently declining, as can be seen in the graph below.

Source: “First in Forestry” report

Sawmills add value to harvested lumber. They have declined for a number of reasons. The biggest reasons for the drop are the increased reliance on questionable-quality imported lumber sold through large retailers and a slew of regulations that make selling North Carolina–produced lumber more difficult. It is increasingly difficult for local sawmills in North Carolina to sell lumber and make money.

Regulations and the Inspection Process

Currently, for a sawmill to sell processed lumber, it must first be inspected by a lumber inspector licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. There are not many inspectors in the state to begin with, and according to stakeholders, it can be incredibly difficult to get one to travel out to the mills, which are sometimes hours away from major cities. In addition, many lumber inspectors are pay-to-grade, meaning the sawmill pays them, which can cost the sawmill around $1,000 a day, essentially wiping out lumber profits.

Even if the sawmill can get an inspector out, the process comes at a cost. The inspection process requires paid employees of the sawmill to rotate each piece of wood on all four sides as it is being inspected. One local sawmill owner stated that this process alone costs him an additional $40/hr.

That $40/hr. doesn’t even tell the whole price. There is an opportunity cost of paying employees to spend time flipping lumber over for the inspector rather than doing something productive to help increase the sawmill’s profitability.

All lumber that is not inspected cannot currently be sold in stores, to private buyers, or to developers. As a result, tons of good quality local lumber is thrown out.

To make matters worse, the standards for what makes lumber “good” supposedly changes often. According to industry professionals, the inspection process for imported lumber is more lenient than local lumber. Lumber you would find at a local hardware and home improvement retailer may be of a much lower quality than the lumber you could get from a local sawmill, but it is sold at the same price.

The “Support Local Sawmills” Act

For the last several years a bill has been introduced that would change the game for local sawmills. House Bill 295, the “Support Local Sawmills” Act, would allow the selling of ungraded lumber from small local sawmills to private buyers (or representatives of private buyers) for use in producing single-family dwellings.

In the 2021-2022 legislative session, this bill passed the House but was stalled in the Senate. Now, once again, the bill has passed the House and is currently being considered by the Senate Committee on Commerce and Insurance after passing the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Energy, and Environment.

To combat fears of poor quality and to deal with inspector shortages, the bill would request the North Carolina Cooperative Extension, Forestry Extension, and North Carolina Forest Service to develop a lumber grading certification and training program for sawmills. The bill would also require that all unstamped lumber sold still meet the requirements of grade-stamped lumber.

Those would be positive steps in the right direction for North Carolina’s lumber industry as well as for homebuyers. Developing a certification program would be a better and more immediate solution to the problems than instituting a licensing program for separate inspectors, and it would empower sawmill employees and owners by allowing them to grade their own lumber.

There are other ways to address these problems. For example, while many large apartment developments no longer use wood at all and instead focus more on concrete and aluminum, multifamily housing — such as townhomes, duplexes, and triplexes — still rely on lumber. Those projects could also benefit from the sale of ungraded lumber from small local sawmills.

Local sawmills should also be allowed to sell directly to retailers. As of now, HB 295 would allow for direct sales of ungraded lumber only to private buyers for their own use, not retail. Allowing the selling of ungraded local lumber in stores would decrease dependence on imported, lower-quality lumber and support small business and North Carolina’s lumber industry. Furthermore, it would also stop some of the lumber waste each year.

Conclusion

Sawmills are closing in North Carolina and local lumber goes to waste even while a housing crisis looms. HB 295 would take sensible steps in deregulating the state’s lumber industry to address these problems. Further deregulation, including direct lumber sales to retailers, would help the lumber industry — and homebuyers — in North Carolina even more.