- Increased fuel efficiency and more electric vehicles may render the gas tax obsolete

- New methods to pay for North Carolina roads must follow the user-pays principle, meaning drivers pay in proportion to their road use

- Mileage-based user fees, if applied in a private and cost-effective manner, could be the key to sustaining North Carolina roads

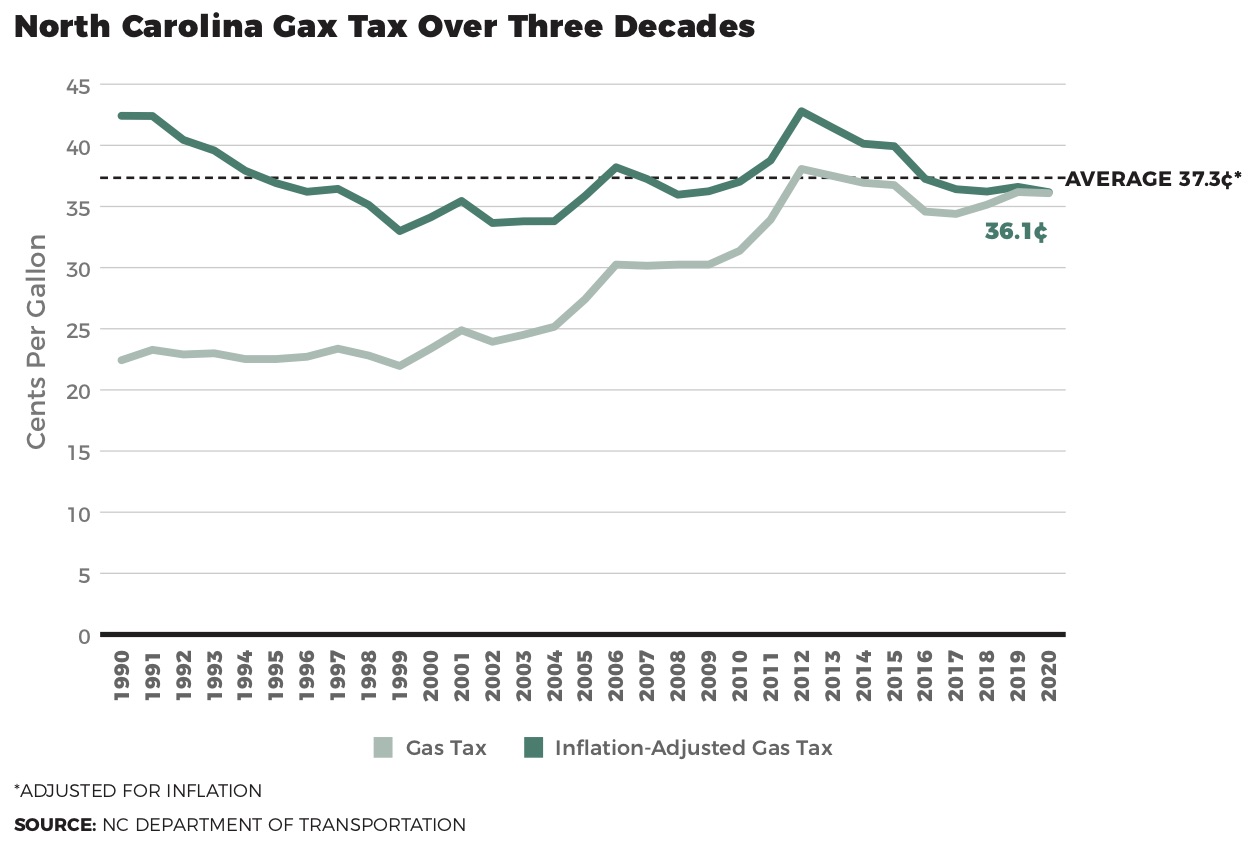

Gas prices may be out of control, but North Carolina’s motor fuels tax (the gas tax) has remained at steady levels for 30 years, when adjusted for inflation.

During the pandemic, the North Carolina General Assembly froze the gas tax rate at 36.1 cents per gallon. That has since been lifted. The state’s gas tax for 2022 is 38.5 cents per gallon.

But with an increasing share of electric vehicles (EVs) in the vehicle market, rising costs of roads and construction, and more fuel-efficient vehicles, the gas tax is up for debate. Today, vehicles use half the energy per mile than they did in the 1970s. As these trends continue, the gas tax may be insufficient to cover the cost of our roads.

What is the best way to fund North Carolina’s transportation needs?

First, where should the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) focus its funds? Transportation funding in our state primarily means roads (including highways). NCDOT is a highway agency as nearly 80% of its $5 billionannual budget is spent on roads and highways. This makes sense because, on the revenue side, 98% of the NCDOT funds come from road users. When federal funding is included, the state gas tax still represents the largest share of revenue sources. Any non-road transportation spending is really being subsidized by road users.

Unlike the vast majority of the country, in North Carolina the state government owns well over half of the road miles in the state. As challenges arrive, lawmakers will need to propose new solutions to build and maintain roads.

Railroads, airports, and other modes of transportation are important but should not take priority as projects for state funding. Using NCDOT funds to subsidize Amtrak and noncommercial airports, for example, primarily benefits the high-income individuals who use them. This regressive funding structure should be exchanged for focusing on roads and the modes of transportation that taxpayers actually pay for and use.

Any budget should reflect the value of those contributing to it, not a handful of political leaders.

The gas tax represents the largest share of NCDOT revenues. But the gas tax may soon be insufficient to fund road building and maintenance as cars become increasingly fuel-efficient and as EVs increase as a share in the vehicle market (in part due to mandates).

The gas tax does rise in an attempt keep up with inflation, but it is not directly tied to overall inflation measures. Instead, the tax is based on a formula defined in state law. It is primarily subject to changes in the state’s population and changes to the energy index portion of the Consumer Price Index. This tax is included in the sky-high prices you see at the pump.

On January 7, Gov. Roy Cooper issued a sweeping executive order that would further antiquate the gas tax by putting well over a million vehicles not subject to it on the roads within a few years. Cooper ordered the state to “strive to … reduce statewide GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions to at least 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions as soon as possible, no later than 2050; and increase the total number of registered, ZEVs [zero-emission vehicles] to at least 1,250,000 by 2030” among other items.

The order is vague, and Cooper lacks the authority to enforce such a declaration. As my colleague Jon Sanders wrote: “a politician’s goal is not a citizen’s legal obligation.” Of course, declaring arbitrary goalposts for EV use is outside politicians’ power. However, the order does signify more state promotion of consumer adoption of EVs and could end up becoming a rule created by a state agency.

What then is the solution? The John Locke Foundation has long advocated for a mileage-based user fee system (MBUF). A Locke research report by Randal O’Toole of the Cato Institute reads: “The premise of MBUF is that people should pay proportionate to their road consumption and the potential damage they do to the roads.”

Calculating miles traveled presents new complications. Privacy and cost of implementation are among the chief concerns. MBUF proposals often suggest using an onboard vehicle device that could capture the distance driven. Though other creative methods are likely available, consumers could be protected by paying fees to insurance companies rather than the state. This data could later be deleted to alleviate privacy concerns.

Oregon experimented with MBUF using a volunteer system at first. Drivers had the option to opt in to pay for vehicle miles traveled. This could lower the cost by testing operability on a smaller sample of willing drivers.

For low-income users, the state could offer transportation vouchers. Our current regressive gas tax is disproportionately harming low-income households. Low-income families pay a greater share of their income on the gas tax and on transportation costs overall. Additionally, working-class jobs are less likely to allow employees to work from home to avoid a commute. Low-income families are not able to afford EVs and fuel-efficient vehicles that would reduce their gas tax burden. A change to MBUF could reduce the cost to low-income families.

Most importantly, from a tax standpoint, mileage-based fees follow the crucial user-pays principle. Other states have already begun moving toward a user-based fee system. In North Carolina, where the state owns the majority of roads, moving to MBUF is of particular importance.