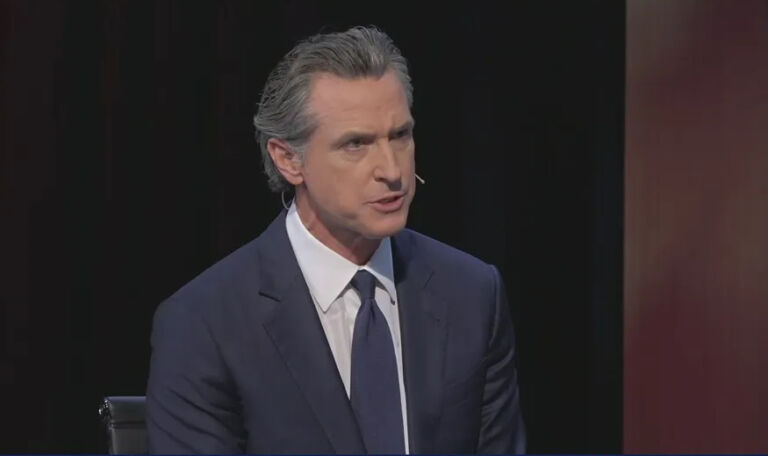

Democratic Governor of California Gavin Newsom made headlines last week after he tweeted that doctors should be “able to write prescriptions for housing the same way they do for insulin or antibiotics.” Madison Dibble from the Washington Examiner reported:

In a series of tweets on Friday, the Democrat argued healthcare and homelessness are not separate problems. He suggested doctors should be able to prescribe a place to stay if they are treating a mentally ill person who does not have stable housing.

“Doctors should be able to write prescriptions for housing the same way they do for insulin or antibiotics,” Newsom said. “We need to start targeting social determinants of health. We need to start treating brain health like we do physical health. What’s more fundamental to a person’s well being than a roof over their head?”

A Kaiser Family Foundation brief defines social determinants of health as “factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care.” The theory is that addressing factors outside of traditional health care, such as a lack of housing, food, employment, etc., will reduce the number of resources that the medical system must allocate to needy patients.

Social determinants of health have garnered a lot of buzz in recent years among researchers and government officials. In this research brief, I will examine where North Carolina has invested in addressing social determinants of health in its Medicaid program and why North Carolina should avoid the California model.

Healthy Opportunities Pilot

Traditionally, Medicaid funding can’t be used for non-medical spending. But in 2018, the federal government approved a waiver that granted North Carolina the ability experiment with a “Health Opportunities Pilot” under its transition to Medicaid managed care. (North Carolina was to transition to a Medicaid managed care model in 2019 and 2020, but Governor Cooper’s veto of the budget and a stand-alone mini-budget for Medicaid transformation delayed the rollout.) CMS approved the Healthy Opportunities Pilot for the following purposes:

The Healthy Opportunities pilots will test the impact of providing selected evidence-based interventions to Medicaid enrollees. Over the next five years, the pilots will provide up to $650 million in Medicaid funding for pilot services in up to three areas of the state that are related to housing, food, transportation and interpersonal safety and directly impact the health outcomes and healthcare costs of enrollees.

The pilot is North Carolina’s experiment to use taxpayer dollars specifically for social determinants of health within the Medicaid program. North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunity Pilot will launch in specific regions of the state and will serve between 25,000-50,000 of the total 2.5 million Medicaid beneficiaries.

North Carolina has already entered into the social determinants on one front: NCCARE360. Launched in 2019, NCCARE360 is a digital platform that health plans and providers can access to connect patients with non-profit organizations that provide community resources for the needy. The goal of the system is to provide a centralized location for all non-profits to refer patients more efficiently and allow for tracking of resource referrals to ensure the patient received the service.

I wrote about NCCARE360 back in October of 2018 for the John Locke Foundation blog. Our concern then was that by creating this new state system to incorporate and connect the work that is currently done by non-profits, there would be a chance that the ongoing services provided would be bureaucratized through state coordination. I concluded the blog post:

DHHS, United Way, and their other partners are clearly committed to making NCCARE360 work and extremely optimistic that it will build connections and provide needed information. We hope they are right, but our expectations are more tempered for two reasons. First, real connections and real progress always come down to people, not systems. Second and related, the culture of health and social services may not match the technology solution. There will likely be some improvements in service coordination and data tracking, but unlikely the kind of transformative leap that has been promised.

The future of SDOH in North Carolina

There is a real desire around the country to incorporate non-health related expenses into what a health plan will cover, especially in Medicaid. North Carolina has entered into this area in the form of the Health Opportunities Pilot. But as we have seen in the past with Medicaid budgets, the resources are scarce. Incorporating things like housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal safety prompts a critical question: how far will Medicaid programs go in their quest to pay for non-health related services?

Medicaid’s core objective is to provide health coverage for disadvantaged populations. There are limited resources within the federal and state Medicaid budgets to fund incorporate a wide swath of benefits outside of traditional health care. Especially in a state like North Carolina, whose Medicaid program already serves over one-fifth of the population, careful consideration must be given when deciding how to best use the available resources.

The Healthy Opportunities Pilot raises the same concerns I had with NCCARE360. While formed with good intentions, creating massive systems can often over-complicate existing delivery. North Carolina’s pilot, as currently constructed, is a far cry from what the California governor is recommending (See here for a list of covered services under the Medicaid pilot.) However, North Carolina should avoid going as far as what is being recommended for California’s Medicaid program. Coordinating resources is very different from purchasing housing.

Programs like NCCARE360 and the Health Opportunities Pilot also raise several questions about the extent of government involvement in the lives of citizens. How much should government be coordinating the resources of non-profits who are already currently serving a community? Are there negative consequences associated with trying to coordinate the needs of thousands of individuals through one centrally administered system? Could the data collected by this system be used in objectionable ways?

North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunity Pilot is funded for the next five years. Careful examination of its results will be necessary to determine the future of using taxpayer funding to support social determinants of health measures.