Background

Did you know that North Carolina used to be the nation’s leader in locally owned and operated distilleries? It’s true. In 1904 the state had 745 registered distilleries, 540 of which were operating.1 And they were all outlawed, an entire industry destroyed, by a series of laws culminating in voters passing the first statewide prohibition in the South in 1908.2

Here’s a signature state industry that has only just started coming back. They were legalized again in 1979, but the first one didn’t open until 2005.3 Now there are 57 distilleries in production in North Carolina.4

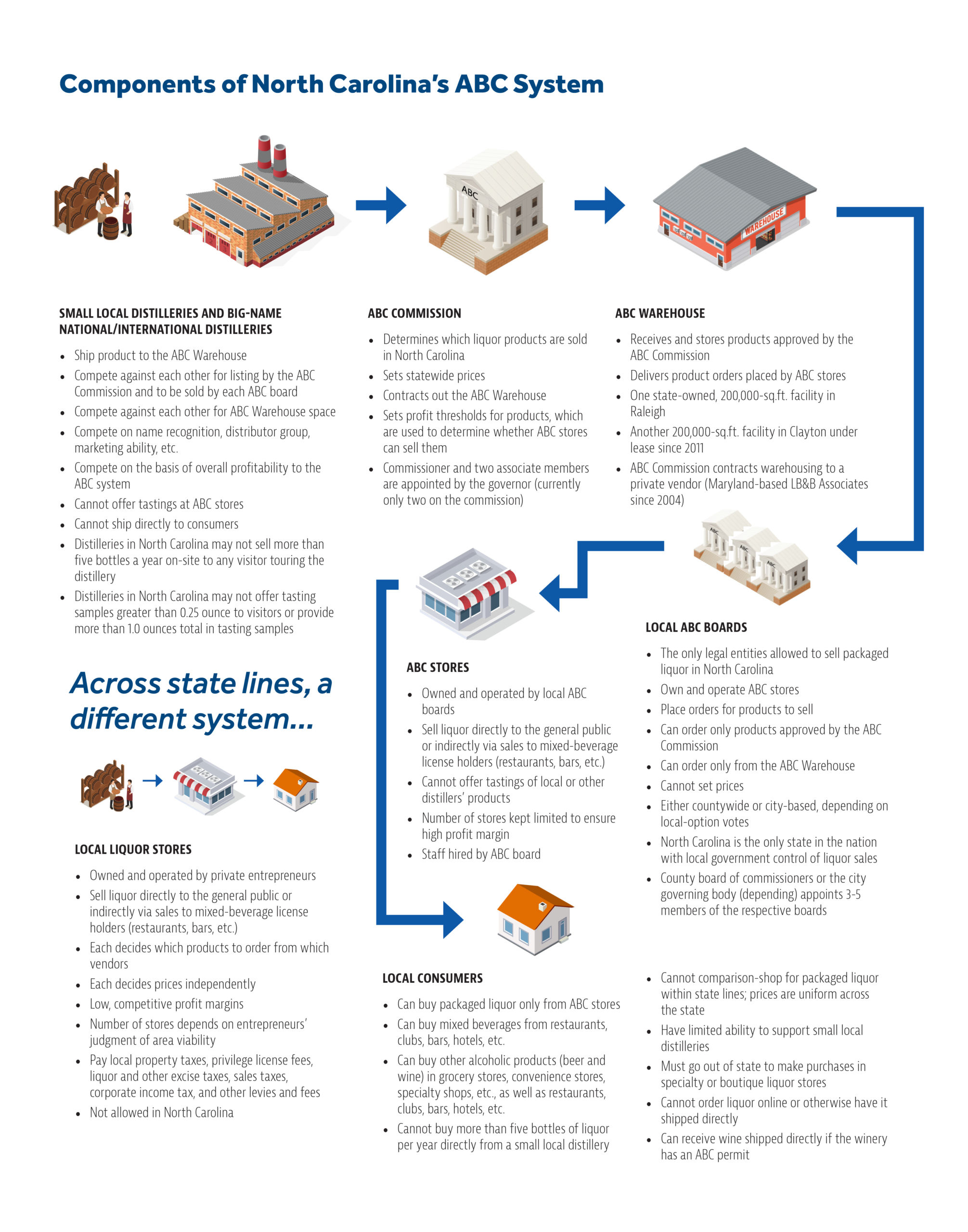

In 1933, federal Prohibition came to an end when the 21st Amendment was ratified (without North Carolina’s help). North Carolina wanted to maintain tight control over liquor sales. A legislative study commission recommended government control over the liquor market out of distrust of private retailers, which led to the Alcohol Beverage Control Act of 1937.5 Its passage officially ended Prohibition in North Carolina and established North Carolina as a control state.

What that means for North Carolina is, the state determines which liquor products from which distilleries may be sold at which prices, owns the central liquor warehouse, and contracts out the management of the warehouse. North Carolina is one of 17 states with government control over the wholesale distribution of liquor, and one of only 13 states with government control over retail distribution.6

The rest of the states have license systems. Wholesale distribution and retail sales of liquor are handled by private enterprises that are licensed by the state.

Here’s where North Carolina is different from other control states: it’s the only one with local government control of retail liquor sales. 7

How did that come about? Before the Alcoholic Beverage Control system (ABC), and even before state prohibition, North Carolina’s local option law of 1874 let county or municipality voters choose whether liquor sales could be allowed in their communities. Under the ABC system, voters in cities and towns in “dry” counties that forbid liquor sales can hold a local-option vote to create a municipal ABC board and open at least one store to sell liquor.

As of this writing, there are 170 ABC boards operating 433 stores across North Carolina.

Less tightly regulated local breweries and wineries are surging

It’s not just that most other states don’t regulate liquor the way North Carolina does. But also, North Carolina doesn’t even regulate other alcoholic beverages this way. The state allows more freedom in beer and wine sales, even though beer and wine have been under ABC jurisdiction since 1948-49.8

This isn’t to say North Carolina’s approach to beer and wine regulation is ideal. It’s not. John Locke Foundation legal policy analyst Jon Guze showed how North Carolina’s wholesale distribution system is holding back the state’s craft brewers and winemakers. His report on all the red tape in North Carolina’s alcohol beverage law made the following findings:

- Overregulating alcohol in North Carolina is harming entrepreneurs, producers, and sellers

- All this red tape is hurting consumers, too, and it’s not letting the economy grow as fast as it could, either

- The biggest impediment to this entrepreneurship is the state’s very limited wholesale distribution system

- North Carolina’s wholesale distribution system enriches distributors while making small craft brewers artificially stay small

- There are 143 pages’ worth of regulations and 123 pages of statutory law dealing with alcohol policy in North Carolina, and 43 different kinds of permits and licenses involved in different activities concerning alcohol sales

- All this red tape favors big producers, distributors, and sellers who can afford to pay compliance staff to make sure they’re up-to-date with all the rules

- The “little guys,” the small craft breweries and the startups, face a huge barrier having to get up to speed on such a massive amount of red tape on top of handling all the other demands of their businesses9

Nevertheless, North Carolina’s craft brewing and winemaking industries have been surging. This century alone, in-state wineries have expanded from 21 to 186.10 Craft breweries have ballooned from 30 to 304.11

Local entrepreneurship in alcohol is thriving in North Carolina

Jon Guze’s report showed that these state industries could flourish with more flexible rules letting brewers and wineries sell directly to retailers if they wanted to, without being forced to go through third-party wholesalers.12

North Carolina’s new local distillery industry holds great potential for growth. These budding entrepreneurs and their employees operate under the state’s significantly stricter control model. Restoring freedom in this industry and putting it on par with beer and wine would spur innovation and development here as well.

‘Contrary to the genius of a free state’

“First in Freedom.” North Carolina is duly proud of this claim and the history behind it. It even adorns our license plates.13

This freedom is not limited to personal freedom. It’s economic freedom as well. The North Carolina State Constitution recognizes people’s self-evident right to “the enjoyment of the fruits of their own labor” and talks about “the genius of a free state.” Specifically, it forbids perpetuities and monopolies as “contrary to the genius of a free state.”14

True, the state does allow some monopolies, such as in providing utilities like electricity, water, etc. Those things are generally considered “natural monopolies,” under the idea that some industries have such extremely high fixed and startup costs that each industry can support only one provider.15 But that is clearly not the case for the distillery industry.

The North Carolina Department of Commerce also stresses the importance of economic freedom on its website, proclaiming “NC is for business”16 (their emphasis) and promoting the state’s business climate:

We’re committed to making it easy for companies to do business in North Carolina. That’s why our state fosters a pro-business environment, fueled by the lowest corporate income tax in the U.S. along with a favorable legal and regulatory climate, low business costs and qualified talent.17

The simple fact of the matter is that government is not suitable for private business. It’s not only contrary to the genius of a free state, but it’s also open to problems unique to government. Government-operated enterprise tends to inefficiencies because of politics and bureaucracy. It resists innovation because it’s insulated from competitive pressures.

Also, because it’s safe from any outside market competition, a government enterprise carries a greater temptation for corruption. All of these problems have been seen in the ABC system.

In 2009-10, the ABC system was hit with several scandals: ritzy travel, six-figure salaries, and five-figure bonuses for the administrator of the New Hanover County ABC Board and his son;18 a $21,000 raise for the head of the Asheville ABC Board;19 a $12,700 dinner party lavished on members of the Mecklenburg County ABC Board by a leading alcohol importer.20 The scandals ushered in talk of freeing and modernizing North Carolina’s approach to alcohol regulation, but state leaders opted to retain tight control instead, with some ethics reforms.

On August 9, 2018, the Office of State Auditor released an audit that made numerous damaging findings about the ABC management. They included:

- Poor contract administration cost the state at least $11.3 million over 13 years

- Unused warehouse space cost the state up to $2.1 million over seven years

- Lack of monitoring cost the state nearly $300,000 over two years21

Regardless of those findings, a Nov. 14, 2018 email to suppliers from the ABC Commission praised the warehouse operator, Maryland-based LB&B Associates, and announced it was cutting the number of products it lists. This included de-listing some North Carolina distilleries’ products.22

The email explained the ABC Commission would “delist products that do not meet 2017/18 profit thresholds for NC ABC boards — $15,000 for vodkas, $10,000 for other, $5,000 for N.C. products, $1,000 for boutique … and use additional filters including trends and numbers of similar products.”23

It’s difficult for upstart, relatively unknown North Carolina distilleries to crack the ABC Commission’s list, even with a lower profit threshold than the big names. The ABC Commission is the only game in town (or state). No one else here can give them a chance under current law. It would be a crime subject to fines and even incarceration.24 Local boards must order only from the ABC Commission’s approved list. Also, there aren’t any local independent stores that might give a local venture a chance.

The profit threshold is a byproduct of the alcohol monopoly in a market that would otherwise be fully competitive. A monopoly charges monopoly prices and enjoys a higher profit margin than it would with competition. Monopolies are inefficient, prevent many sales, and create deadweight loss in an economy.25 That’s what makes them “contrary to the genius of a free state.”

The higher the monopoly profits on liquor sales in the ABC system are, the more the system is considered a success by government officials. In 2008, the Program Evaluation Division (PED) of the North Carolina General Assembly issued a report on modernizing the ABC system, and many of its recommendations were aimed at increasing system profits.26 In 2018, PED issued a follow-report on its success, as system profits had increased from 8.5 percent in 2011 to 11.2 percent in 2017.27

By way of comparison, the profit margin of private beer, wine, and liquor stores nationally in 2017 hovered around 2.4 percent.28 Only 19 of the 428 government-controlled liquor stores fell below that 2.4 percent profit margin seen in a competitive market. That’s the margin the ABC Commission is protecting and seeking to expand, which includes de-listing or not listing products from newcomer North Carolina distilleries.

Distillers in most other states (the license states) don’t have this problem, of course. For that matter, neither do North Carolina’s craft brewers and wineries.

Time to bring competition into North Carolina’s market for liquor

It’s been eight decades since North Carolina’s ABC system was devised. The system has resisted change even as public preferences haven’t. Some changes have come, but slowly, and usually after years of trying.

At first, ABC sales were exclusively for home consumption. But people wanted to enjoy drinks in social venues such as private clubs and restaurants, so eventually the Brown-Bagging Act of 1967 was passed to allow consumers to bring their own liquor to such places.29 Liquor-by-the-drink legislation was passed in 1978 after several years of attempts.30 In 2017, the General Assembly passed the “Brunch Bill” so localities could approve retailers and restaurants selling alcohol beginning at 10 a.m. (brunch) on Sundays instead of noon (after churches let out).31

Still, other long-time prohibitions remain, including bans on happy hours, offering certain drink specials, selling alcohol at bingo games, and many more.32 Also, ABC stores still close on Sundays.

But the changes show tension with the ABC system’s strict control foundation. North Carolinians can now get mixed drinks in restaurants, bars, taverns, and other privately run enterprises. Beer and wine are available in grocery stores, convenience marts, specialty shops, restaurants, taverns, bars, etc., and at competitive prices. Wineries and breweries are flourishing, and even distilleries are coming back.

Last year’s audit rekindled interest in loosening and modernizing North Carolina’s approach to alcohol regulation.33 There are many reasons why moving the state away from control to a competitive system is due:

- Competition works for other states, and for beer and wine in North Carolina

- Competition would encourage entrepreneurship and innovation in licensed stores and specialty shops

- Competition would also foster development of state distilleries by allowing them to compete for shelf space in individual stores, rather than for space in the one central warehouse as determined by the one state decision-making body

- Competition would serve communities by bringing in more retail outlets and more jobs, with private retailers bearing operating costs and risks

- Competition would remove a potential avenue for public corruption and waste presented by an inefficient government monopoly over business enterprise

Any time there is talk of North Carolina loosening its tight control over liquor, people worry about what repercussions there could be, whether on government revenues or social issues and public health. Looking at outcomes in license versus control states should help set these worries aside.

Government revenues in a competitive system

North Carolina’s ABC system generated over $1.1 billion in revenue from liquor sales in fiscal year 2017. The accompanying graph shows how that revenue was distributed.

Only about 36 percent ($406 million) of the ABC system’s revenue goes toward the General Fund and other state and local government uses. Replacing that amount is simply a matter of setting licensing fees and adjusting the menu of excise taxes and other taxes and fees on the sale of liquor.

Economists Andrew J. Buck and Simon Hakim showed how a state’s revenues could be held harmless even when moving from a control model to a competitive model, using excise taxes, sales taxes, and licensing fees. They demonstrated the large revenues West Virginia realized from licensing when that state began selling its state liquor retailing system in 1990.34

When the Canadian province of Alberta opened retail sales of alcohol to independent stores in 1994, the government introduced a new excise tax intended to keep province revenues neutral from the change. The unexpected result was that revenues increased to the point that excise taxes later needed to be lowered.35

Most recently, Washington voters in 2011 passed a referendum to end their state’s control over liquor sales. At the time, Washington had the nation’s highest excise taxes and fees on spirits.36 Today, it still does.37 Interestingly, Washington’s liquor taxes and fees are lower than they were in 2014,38 but their effect on state revenues has been described in news reports as a “windfall.”39

The local distillers in Washington? The Spokesman-Review reported on December 8, 2017:

The fees are also a source of friction for distributors. Nathan Kaiser, the vice president of the Washington Distillers Guild, said it’s been tough for some distillers to get started in Washington. …

On the whole, however, privatization is a good thing, Kaiser said. It’s what allowed his business to flourish and sell bourbon across Washington (and also in Oregon and Idaho).40

Local governments would also reap one-time windfalls from the sale of ABC stores, as well as collect ongoing property taxes from them in the future.41

As for the remaining 64 percent of ABC revenues, they are used to cover operating overhead. Under a competitive system, individual stores would be responsible for that.

Social and public-health outcomes don’t depend on government control

On the issue of social and public-health repercussions from moving to a competitive system, a 2012 study by economists Michael LaFaive and Antony Davies looked at average annual alcohol-attributable deaths per 100,000 in each of the 50 states from 2001 to 2005. In their chart, 23 license states posted lower rates than did North Carolina.42

A 2010 study by Davies and economist John Pulito examined the “numerous studies” on state liquor controls and found “no clear evidence that privatization of alcohol markets leads to either an increase or a decrease in underage drinking, underage binge drinking, or DUI fatalities. Studies showing a positive relationship … are counterbalanced by others showing an absent or ambiguous relationship.”43

A 2009 study by Davies and Pulito found that “Evidence from 48 states over time shows no link between market controls and these social goals” of “reducing alcohol consumption, underage drinking, and alcohol-related traffic deaths.”44 Economists Donald J. Boudreaux and Julia Williams also found no link in their 2010 report, writing that “The plain fact seems to be that alcohol-related problems are unrelated to whether or not a state government prevents private, competitive businesses from selling spirits to the general public.”45

Numerous studies find that privatizing alcohol markets often leads to increased prices,46 which would dampen consumption effects. The most recent state to relax liquor controls, Washington, has seen prices increase overall despite varied prices across outlets. Local distilleries found state taxes and fees burdensome but the greater freedom overall to be a boon.47

If anything, strict control over liquor sales is merely shifting alcohol consumption away from liquor and toward beer and wine. Most people who enjoy alcoholic beverages don’t exclusively buy one type, but they do tend to favor beer and wine over liquor. This suggests wine and beer are effective substitute goods for liquor if liquor is made harder and costlier to get than wine and beer.48

Looking at the Southeastern U.S. region (including the District of Columbia), while the four retail control states are at the bottom in per-capita consumption of liquor, they rank higher than many license states in per-capita consumption of beer and wine. North Carolina ranked 13th out of 14 in per-capita liquor sales, but the state was 8th in beer consumption and 4th in wine consumption per capita.49

Summary

North Carolina opened the 20th century as the nation’s leader in legal distilleries. The state ABC system was devised to control liquor sales, and now North Carolina is one of just 17 states with control over wholesale distribution of liquor, one of only 13 states with government control over retail distribution of liquor, and the only one in the country with local government control of retail sales.

Other states let licensed private businesses handle wholesale and retail sales of liquor. That’s also what North Carolina does for beer and wine sales. Local breweries and wineries are flourishing under a relatively freer distribution system.

North Carolina’s budding distilleries could be doing the same if given the chance. But the strict control system fosters inefficiency and deadweight loss, and it makes it very hard for small local distilleries to reach North Carolina customers. If they’re not listed by the ABC Commission, they can’t be sold in ABC stores, and that’s that.

Competition works in other states — and in sales of other kinds of alcohol in North Carolina. Competition here would encourage more innovation, more entrepreneurship, more local jobs, and more options for more local distilleries to reach consumers.

State leaders have created hundreds of pages full of laws and rules in state statutes and administrative code restricting the state’s alcohol industry. Many of these are outdated or plain out of line with consumer wants, local entrepreneurs’ needs, and what the state constitution applauds as “the genius of a free state.”

Recommendations

Rethink and restructure Chapter 18B of the North Carolina General Statues, which is the chapter of laws about alcoholic beverages.

Allow more competition in liquor distribution and sales in North Carolina.

Remove red tape in alcohol beverage sales overall.

Let the debate on these things begin here, where we celebrate being “First in Freedom.”

Endnotes

- “2011 Annual Report,” North Carolina Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission, https://portal.abc.nc.gov/Public%20Web%20Documents/Divisions/Public%20Resources/Annual%20Reports/2011%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

- K. Todd Johnson, “Prohibition,” Encyclopedia of North Carolina, 2006, https://www.ncpedia.org/prohibition; Ben Steelman, “North Carolina has complex history with liquor,” StarNews, March 6, 2010, https://www.starnewsonline.com/news/20100306/north-carolina-has-complex-history-with-liquor.

- John Trump, “State laws impede craft beverages,” Carolina Journal, December 9, 2016, https://www.carolinajournal.com/opinion-article/state-rules-are-the-main-barrier-to-the-craft-of-producing-alcohol.

- “2018 Annual Report” (preliminary), North Carolina Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission, https://portal.abc.nc.gov/Public%20Web%20Documents/Divisions/Public%20Resources/Annual%20Reports/2018%20Annual%20Report%20(Published%20December%2031,%202018).pdf.

- Steelman, “North Carolina has complex history with liquor.”

- State alcohol control systems as delineated by the federal Alcohol Policy Information System, a project of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health, https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov.

- “North Carolina’s Alcohol Beverage Control System Is Outdated and Needs Modernization,” Program Evaluation Division, North Carolina General Assembly, Report No. 2008-12-01, December 2008, https://www.ncleg.net/ped/reports/documents/abc/abc_report.pdf.

- Steelman, “North Carolina has complex history with liquor.”

- Jon Guze, “Hard to Swallow: Maze Of Rules Hinders Expansion Of State’s Alcoholic Beverage Industry,” Spotlight No. 482, John Locke Foundation, November 28, 2016, https://www.johnlocke.org/research/alcoholic-beverage-regulation-hard-to-swallow.

- See “North Carolina Wine History,” North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, http://www.ncagr.gov/markets/ncwine/about-us/nc-wine-history.html, and “North Carolina Wine Industry Facts,” NC Wine, as of August 28, 2017, https://www.ncwine.org/media.

- See Karl E. Campbell, “Beer and Breweries,” Encyclopedia of North Carolina, 2006, https://www.ncpedia.org/beer-and-breweries, and author’s count of “NC Breweries” listed by NC Beer Guys, https://www.ncbeerguys.com/nc-breweries.

- Guze, “Hard to Swallow: Maze Of Rules Hinders Expansion.”

- Troy Kickler, “What ‘First in Freedom’ means, North State Journal, April 12, 2017, https://nsjonline.com/article/2017/04/kickler-what-first-in-freedom-means.

- North Carolina State Constitution, Article 1, Section 34, https://www.ncleg.gov/EnactedLegislation/Constitution/NCConstitution.html.

- See, e.g., Will Kenton, “Natural Monopoly,” Investopedia, April 17, 2018, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/natural_monopoly.asp.

- North Carolina Department of Commerce, home page, accessed January 31, 2019, https://www.nccommerce.com.

- “Why North Carolina,” NC Dept. of Commerce, accessed January 31, 2019, https://www.nccommerce.com/business/why-north-carolina.

- Bruce Mildwurf, “State liquor regulators adopt ethics reforms,” WRAL, January 13, 2010, https://www.wral.com/state-liquor-regulators-adopt-ethics-reforms/6798818.

- Kelcey Carlson, “Former ABC board member defends, questions salaries,” WRAL, January 11, 2010, https://www.wral.com/former-abc-board-member-defends-questions-salaries/6786057.

- Mildwurf, “State liquor regulators adopt ethics reforms.”

- “Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission Warehouse Contract,” Performance Audit, North Carolina Office of State Auditor, August 2018, https://www.ncauditor.net/EPSWeb/Reports/Performance/PER-2017-4900.pdf.

- John Trump, “State ABC cutting options on shelves as it praises controversial warehouse operator,” Carolina Journal, November 21, 2018, https://www.carolinajournal.com/news-article/state-abc-cutting-options-on-shelves-as-it-praises-controversial-warehouse-operator.

- Trump, “State ABC cutting options on shelves.”

- North Carolina General Statutes § 18B-102, https://www.ncleg.gov/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/BySection/Chapter_18B/GS_18B-102.html; cf. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15A-1340.23, https://www.ncleg.net/EnactedLegislation/Statutes/HTML/BySection/Chapter_15A/GS_15A-1340.23.html.

- For discussion, see Jon Sanders, “The ABC System and deadweight loss,” The Locker Room blog, John Locke Foundation, January 23, 2019, https://lockerroom.johnlocke.org/2019/01/23/the-abc-system-and-deadweight-loss.

- “North Carolina’s Alcohol Beverage Control System Is Outdated and Needs Modernization,” Program Evaluation Division. See discussion in Jon Sanders, “The ABC System Wants to Repurpose While Keeping Tight Control ,” Research Brief, John Locke Foundation, January 23, 2019, https://www.johnlocke.org/update/the-abc-system-wants-to-repurpose-while-keeping-tight-control.

- “Follow-Up Report: Implementation of PED Recommendations Has Improved Local ABC Board Profitability and Operational Efficiency,” Program Evaluation Division, North Carolina General Assembly, Report Number 2018-05, May 21, 2018, https://www.ncleg.net/PED/Reports/documents/ABC_Follow/ABC_Follow_Report.pdf. Also see “Profit Percent to Sales: Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017,” ABC Commission, https://portal.abc.nc.gov/Public%20Web%20Documents/Divisions/Local%20ABC%20Boards/Sales%20and%20Revenue%20Reports/1.%20ABC%20Board%20Profit%20Percent%20to%20Revenue/Profit%20Percent%20Sales%202017.pdf.

- Mary Ellen Biery, “These Industries Generate The Lowest Profit Margins,” Forbes September 24, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/sageworks/2017/09/24/these-industries-generate-the-lowest-profit-margins.

- “North Carolina’s Alcohol Beverage Control System Is Outdated and Needs Modernization,” Program Evaluation Division.

- Michael Crowell, “A History of Liquor-by-the-Drink Legislation in North Carolina,” 1 Campbell L. Rev. 61 (1979), https://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=clr.

- John Trump, “‘Brunch bill’ a big hit across state,” Carolina Journal, August 23, 2017, https://www.carolinajournal.com/news-article/brunch-bill-a-big-hit-across-state.

- Guze, “Hard to Swallow: Maze Of Rules Hinders Expansion.”

- John Trump and Kari Travis, “Recent turmoil at ABC suggests reforms are overdue, McGrady says,” Carolina Journal, August 17, 2018, https://www.carolinajournal.com/news-article/recent-turmoil-at-abc-suggests-reforms-are-overdue-mcgrady-says.

- Andrew J. Buck and Simon Hakim, “Privatization of Alcohol Beverage Distribution in Pennsylvania,” Center for Competitive Government, Fox School of Business, Temple University, 1991, http://ajbuckeconbikesail.net/wkpapers/alcohol/COMMON.html.

- Björn Trolldal, “An investigation into the effect of privatization of retail sales of alcohol on consumption and traffic accidents in Alberta, Canada,” Addiction 100(5):662-71, June 2005, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7889266_An_investigation_of_the_effect_of_privatization_of_retail_sales_of_alcohol_on_consumption_and_traffic_accidents_in_Alberta_Canada.

- “State Excise Tax Rates on Spirits, 2007-2013,” Tax Foundation, April 18, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/state-excise-tax-rates-spirits-2007-2013.

- Morgan Scarboro, “How High are Spirits Taxes in Your State?”, Tax Foundation, March 22, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-spirits-taxes-2018.

- Liz Malm, Richard Borean, and Lyman Stone, “Map: Spirits Excise Tax Rates by State, 2014,” Tax Foundation, February 13, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/map-spirits-excise-tax-rates-state-2014.

- Chad Sokol, “5 years after privatization, Washington liquor sales are up despite price increase,” The Spokesman-Review, December 13, 2017, http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2017/dec/13/5-years-after-privatization-washington-liquor-sale.

- Sokol, “5 years after privatization, Washington liquor sales.”

- Q.v. discussion in Buck and Hakim, “ Privatization of Alcohol Beverage Distribution in Pennsylvania,” and also “North Carolina’s Alcohol Beverage Control System Is Outdated and Needs Modernization,” Program Evaluation Division.

- Michael LaFaive and Antony Davies, “Alcohol Control Reform and Public Health and Safety,” Policy Brief, Mackinac Center, May 14, 2012, https://www.mackinac.org/S2012-02.

- Antony Davies and John Pulito, “Binge Thinking: A Look at the Social Impact of State Liquor Controls,” Working Paper No. 10-70, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, November 2010, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265615526_working_paper_BiNgE_ThiNkiNg_A_Look_AT_ThE_SociAL_impAcT_of_STATE_Liquor_coNTroLS.

- Antony Davies and John Pulito, “Government-Run Liquor Stores,” Policy Brief, Vol. 21, No. 03, Commonwealth Foundation, October 2009, https://www.commonwealthfoundation.org/issues/detail/government-run-liquor-stores-the-social-impact-of-privatization.

- Donald J. Boudreaux and Julia Williams, “Impaired Judgment: The Failure of Control States to Reduce Alcohol-Related Problems,” Policy Report No. 14, Virginia Institute for Public Policy, June 1, 2010, https://virginiainstitute.org/publications/economy/impaired-judgment-the-failure-of-control-states-to-reduce-alcohol-related-problems.

- E.g., Julian Simon, “The Economic Effects of State Monopoly of Packaged-Liquor Retailing,” Journal of Political Economy 74, no. 2 (Apr., 1966): 188-194, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/259135?journalCode=jpe, and Trolldal, “An investigation into the effect of privatization of retail sales of alcohol.”

- Sokol, “5 years after privatization, Washington liquor sales.”

- See, e.g., “Self-Regulation in the Alcohol Industry,” Federal Trade Commission, March 2014, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/self-regulation-alcohol-industry-report-federal-trade-commission/140320alcoholreport.pdf, p. 6, and also Simon, “The Economic Effects of State Monopoly of Packaged-Liquor Retailing,” and LaFaive and Davies, “Alcohol Control Reform and Public Health and Safety.”

- Jon Sanders, “When Controlling Alcohol Doesn’t Control Alcohol,” Research Brief, John Locke Foundation, January 29, 2019, https://www.johnlocke.org/update/when-controlling-alcohol-doesnt-control-alcohol.