Executive Summary

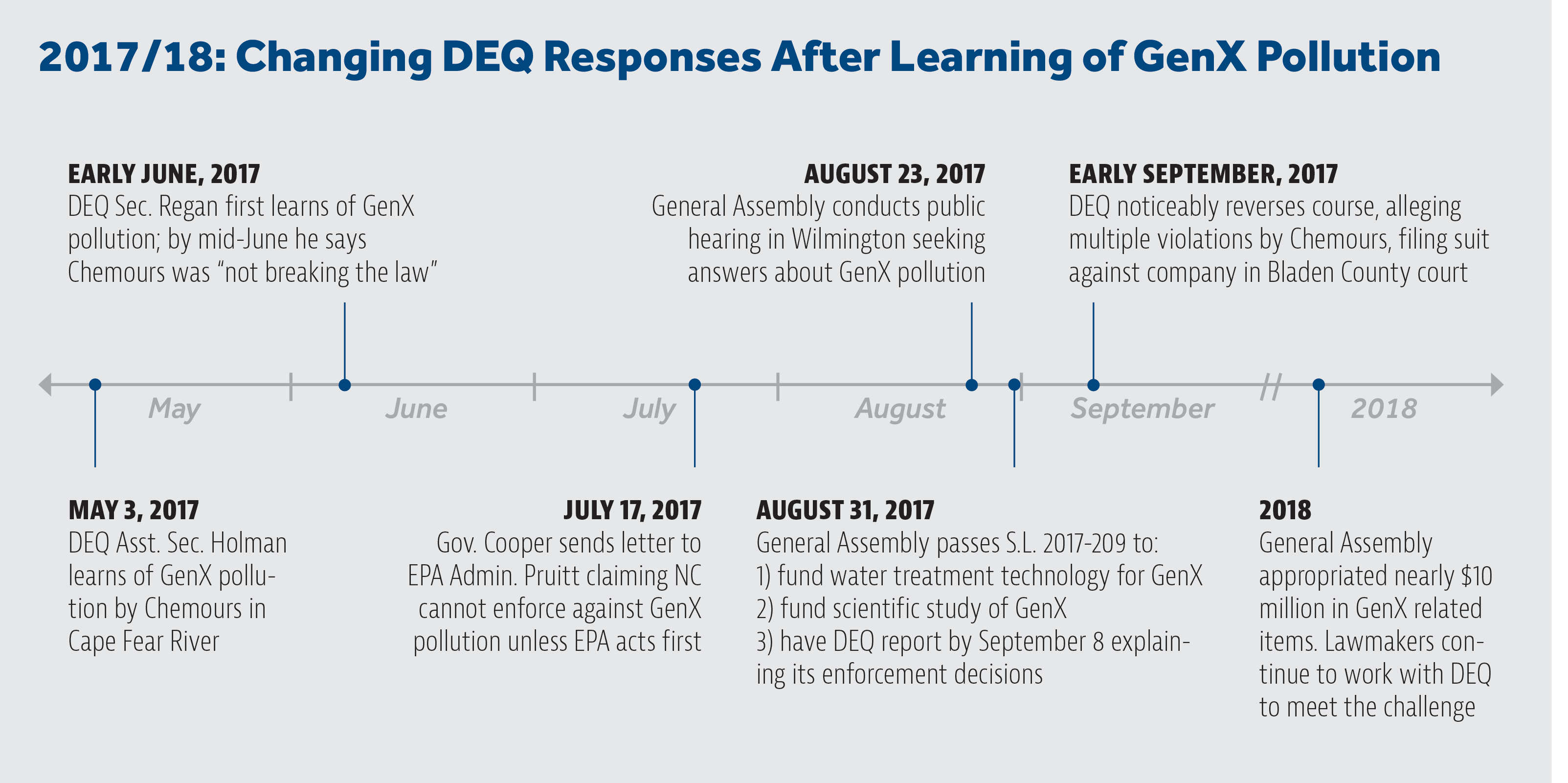

In 2017, North Carolinians were alerted to the discharge of a relatively new, unregulated chemical compound called “GenX” as well as other, similar compounds in the Cape Fear River. This paper uses a question-and-answer format to examine how state and local authorities — from the local water utility on up to state agencies, legislators, and the governor — reacted to the public health crisis in 2017, from when they first learned of it to when they began to take decisive actions. The answers reveal a perplexing pattern of reluctance by state regulators to address the issues — until they were forced into action by outside organizations, including media and the General Assembly, as the chronology below illustrates:

- North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) officials knew about research findings of GenX in the Cape Fear River but did nothing until the StarNews broke the news to the public.

- DHHS hurriedly announced a health goal of GenX of 71,000 nanograms per liter (ng/L), which it would drastically reduce a month later to 140 ng/L, while announcing its assessment did not take cancer risks into account despite acknowledging animal studies demonstrated some cancer effects.

- DEQ officials hastily announced that the company responsible, Chemours, was “not breaking the law” and always had disclosed its discharge in permit applications, meaning that it was shielded from enforcement under the U.S. Clean Water Act.

- Gov. Roy Cooper claimed that North Carolina lacked authority to regulate GenX and other contaminants unless the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency acted first.

- Legislators, experts, the Cape Fear water utility, and members of the public challenged the administration’s misinterpretation of state authority to regulate compounds without EPA action and asked why DEQ had not sent Chemours a Notice of Violation under the Clean Water Act.

- DEQ Secretary Michael Regan and DHHS Secretary Mandy Cohen agreed the state had authority to regulate GenX and related compounds, then requested more funding and staff.

- By late August 2017 at a hearing of the legislature’s Environmental Review Commission, UNC Wilmington marine biologist Laryy Cahoon said he had “no idea” how DEQ came to the conclusion Chemours was not in violation. DEQ Secretary Regan said the agency was still seeking information “as we start looking at whether this company has done anything in terms of a violation.”

- The legislature passed House Bill 56 on August 31, 2017, providing funding for testing, monitoring, and treatment of GenX, as well as scientific study of it. It also gave DEQ until September 8, 2017 to issue Chemours a Notice of Violation or a detailed written report to the legislature explaining why it had not issued a notice.

- In the week that followed, DEQ gave Chemours a 60-day notice of intent to suspend its permit if it didn’t cease discharging GenX-like compounds, then issued a Notice of Violation against Chemours based on groundwater testing results from August, and then filed a comprehensive complaint in Superior Court in Bladen County alleging a wide range of violations by Chemours, including failure to disclose its discharges as required under the Clean Water Act.

- Gov. Cooper vetoed H.B. 56 on September 21, 2017, which the legislature subsequently overrode and codified as S.L. 2017-209.

Introduction

Last year, North Carolinians were alerted to the discharge of a relatively new, unregulated chemical compound called “GenX” as well as other, similar compounds in the Cape Fear River. This paper uses a question-and-answer format to provide a handy guide through a multifaceted timeline involving scientists, local water utility officials, media, members of the public, state regulators, legislators, and the governor. It examines how state officials reacted to the public health crisis in 2017, from when they first learned of it to when they began to take decisive actions.

What is GenX?

GenX is a chemical used to make Teflon, firefighting foam, solar panels, and other products.1 It was introduced by DuPont in 2009 to replace a similar substance called C8 (for its eight carbon atoms), a perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) the company had used for decades but which studies had tied to thyroid disease, kidney cancer, testicular cancer, and other ills.2

How toxic is GenX?

That is the question for which there is no definitive answer. GenX is a relatively new chemical compound, and it is one of several similar compounds. As such, there are few studies of it or them.

What makes GenX, C8, and similar compounds (known as per- and polyfluoroakyl substances, or PFASs) so commercially useful is their high resistance to degradation. This stability is also what makes them potentially dangerous to the environment and our bodies.

Many potentially dangerous chemicals degrade naturally in the environment, limiting their impact if their rate of release into the environment is less than their degradation rate. Highly stable chemical compounds that resist degradation, however, can accumulate even with low rates of release.

A similar dynamic happens in our bodies. How fast can our bodies metabolize and expel a chemical, and how does that compare with our exposure rate to it? C8 was shown to build up in the human body (bioaccumulate) even at very low exposure rates, with suspicions of adverse health effects leading to many lawsuits.

In 2017, DuPont and Chemours, the company it formed in 2015 from its “Performance Chemicals” division, agreed to pay $671 million settled over 3,500 personal injury claims brought against DuPont for C8 contamination in the water from their Parkersburg, West Virginia plant.3 Chemours took over operation of DuPont’s Fayetteville Works plant when it officially split from DuPont.

A key difference between GenX and C8 is that GenX is a smaller compound with fewer (six instead of eight) carbon atoms. For that reason, it is thought that GenX should be less likely to bioaccumulate.4

In 2009 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) entered into a consent agreement with DuPont under the U.S. Toxic Substances Control Act regarding the company’s production of GenX at Fayetteville Works along the Cape Fear River. The company was required to “recover and capture (destroy) or recycle” 99 percent of GenX and another compound from being discharged. The order does not, however, apply to byproducts from producing other substances.5

How did GenX get in the Cape Fear River, and why wasn’t it detected before?

Even though it wasn’t produced commercially until 2009, GenX had been released in the Cape Fear River from the Fayetteville Works plant as far back as 1980 as a byproduct of other chemical production.6

Its presence in the Cape Fear River wasn’t detected until 2012, when EPA scientists found it, thanks to recent technological advances in high-resolution mass spectrometry. The next year, scientists at North Carolina State University, the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, the EPA, and others began testing the water in the Cape Fear River basin outside drinking water treatment facilities.7 They tested for residual PFAS compounds as well as emerging replacement compounds like GenX in the drinking water sources, whether the water treatment plants were removing them, and whether they were adsorbable on activated carbon.

Their research was published in the academic journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters on November 10, 2016. In it, they reported finding high amounts of GenX and also that current water treatment processes were not removing it. They found that GenX was “less adsorbable” than C8 and thus “presents a greater drinking water treatment challenge than PFOA [C8] does.”8

When did DEQ learn of Chemours discharging GenX?

On Nov. 23, 2016, study co-author Detlef Knappe, a professor of civil, construction, and environmental engineering at N.C. State, emailed the published paper to several officials in the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and in several cities. The email noted that levels of “GenX, a replacement for PFOA, were very high in Wilm[ington] (and by association also Brunswick and Pender).” It pointed out that current water treatment processes were not removing GenX and other “newly discovered compounds being discharged by the Chemours plant south of Fayetteville,” many of which were “essentially non-adsorbable on activated carbon.” In sum, “A large number of people are exposed to high levels of PFAS through their drinking water!”9

On Nov. 29, 2016, Prof. Michael Mallin at UNC-Wilmington also emailed the study to officials at DEQ as well as to people from UNC-Wilmington, N.C. State, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Fayetteville Public Works, Cape Fear Public Utility Authority (CFPUA), Cape Fear River Watch, and the North Carolina Coastal Federation.10

On April 19, 2017, officials with CFPUA met with Knappe over the study results and issues regarding sampling and treatment of PFAS compounds. Knappe sought further research and investigation into GenX in the river, ways to remove GenX from the water, and more research to support state regulation of GenX. He told CFPUA Chief Operations Officer Frank Styers there is “Not enough information to say that you shouldn’t drink the water.” Among the attendees was Heidi Cox of DEQ.11

On April 22, 2017, Knappe forwarded to CFPUA Water Operations Supervisor (and paper co-author) Ben Kearns the abstract to a newly released Swedish study on GenX toxicity that “purports that GenX is more toxic than PFOA [C8].” Based on the study’s implications, Knappe urged a “push to dramatically reduce impacts of GenX and similar compounds in the [Cape Fear River].”12

Shortly afterward CFPUA staff began to seek DEQ’s help to get GenX investigated and regulated by the state.13

On May 3, 2017, DEQ Assistant Secretary Sheila Holman was informed about GenX in the Cape Fear River in a meeting with CFPUA.14

On June 8, 2017, the issue was brought to the public’s attention when the Wilmington StarNews published the first report in its “Toxic Tap Water” series on the Cape Fear River contamination.15

DEQ Secretary Michael Regan said he did not learn of GenX in the Cape Fear River until early June.16

How was the state health goal for GenX derived, and why was it changed?

On June 8, 2017, the day the StarNews exposé was published, the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) issued a health goal for GenX of 71,000 nanograms per liter (ng/L, also referred to as parts per trillion or ppt). DHHS said the goal was based on information from the European Chemical Agency, derived from a “2-year rat chronic toxicity/carcinogenicity study,” calculated for drinking water intake by bottle-fed infants, and weighted according to uncertainty factors. A DHHS health goal is a “non-regulatory, non-enforceable level of contamination below which no adverse health effects would be expected over a lifetime of exposure.”17

Shortly afterward, on July 14, 2017, DHHS announced it had dramatically lowered the health goal for GenX to 140 ng/L. This news came on the same day DEQ released results of its testing for GenX along the Cape Fear River from June 19 to July 9.18

DHHS said this new goal was derived from a different study, based on GenX effects on the livers of mice. The same adjustments are used with two important changes: it is given an additional weight factor of 10 because the study used was a subchronic toxicity study rather than a chronic toxicity study, and it is weighted further on an assumption that only 20 percent of potential GenX exposure could be from drinking water (allowing for other contamination routes, such as air, dust, soil, or food).19

DHHS’s assessment did not take into account cancer risks in setting the health goal despite noting that “animal studies demonstrate liver and red blood cell non-cancer effects and pancreas, liver, and testicular cancer effects.” The reasons given were that “there is not enough information at this time to identify a specific level of GenX that might be associated with an increased risk for cancer” and the uncertainty over “[w]hether or not animal effects will be the same in humans.”20

DHHS did not issue a “do not drink” order for drinking water levels of GenX above 140 ng/L. It explained that 140 ng/L “represents the concentration of GenX at which no adverse non-cancer health effects would be anticipated over an entire lifetime to the most sensitive population.”21

DHHS had released on June 29, 2017, an analysis of the rates of five types of cancer in the Cape Fear region. DHHS found that cancer rates were “generally similar to the statewide rates of pancreatic, liver, uterine, testicular, and kidney cancers.” Exceptions were a higher 20-year rate of testicular cancer and a higher five-year rate of liver cancer in New Hanover County; lower 20-year and five-year rates of pancreatic cancer and a lower five-year rate of uterine cancer in Brunswick County; and a lower 20-year rate of kidney cancer in Bladen County.22

When did DEQ begin to address GenX, and what did it do?

On June 14, 2017, DEQ opened an investigation with DHHS into GenX in the Cape Fear River. The next day, DEQ Secretary Regan announced at a community meeting in Wilmington that Chemours was in compliance with its National Pollution Discharge Elimination System permit (part of the U.S. Clean Water Act), since the EPA does not regulate GenX as a pollutant.23

“What we have here is a situation where the company is not breaking the law,” Regan said.24

Later that month, DEQ spokesman Jamie Kritzer told StarNews that Chemours had identified their discharge of GenX and related compounds in all their permit applications. StarNews reported:

In an email, Kritzer wrote: “They (GenX and the ‘novel’ substances) were all identified in the 2016 application and all previous applications as HFPO [hexafluoropropylene oxide] monomer (which are being referred to as GenX) and the vinyl ether monomers.”25

This statement is significant because disclosure would shield Chemours from enforcement under the Clean Water Act. The law provides such a shield when an applicant discloses the discharge of pollutants and receives a permit from DEQ with full knowledge of that discharge. But did those permit applications, in fact, disclose the discharge?

StarNews asked a retired former DEQ regulator:

Rick Shiver, who was surface water regional supervisor at the Wilmington office of DEQ’s Water Resources division before retiring in 2011, spent much of his 38-year career reviewing and commenting on NPDES permit applications from companies in Southeastern North Carolina.

“I would not understand that this process generated GenX as a byproduct,” Shiver said when shown a copy of the paragraph. “I don’t think anyone in the regional office would understand that.”26

Although Kritzer stated that the HFPO monomer referenced in permit applications is now what is “referred to as GenX,” Knappe said it is “incorrect” to use them interchangeably, since “GenX is a product that forms from HFPO monomer.” Also, the applications did not make clear that GenX and related compounds were in the wastewater.27

On June 19, 2017, officials at CFPUA sent a letter to Secretary Regan requesting that DEQ take several actions regarding GenX and related compounds in the Cape Fear River, including:

- Conduct extensive sampling and testing, including storage of samples for testing later as new analytical methods become available

- Develop a water quality–based effluent level for GenX discharges and add it to Chemours’ permit

- Develop a technology-based effluent level for GenX discharges and add it to Chemours’ permit

- In lieu of developing those effluent levels, condition Chemours’ permit to prohibit GenX discharge28

Importantly, the letter cited DEQ’s statutory authority to take such actions, stressing that developing a technology-based effluent level is “mandated by state statute.”29

On June 19, 2017, DEQ began tests (paid for by Chemours) for GenX of 13 sites along the Cape Fear River.30

On June 20, 2017, Chemours announced it would voluntarily stop discharging GenX in the Cape Fear River and instead “capture, remove, and safely dispose of” the wastewater. DEQ inspectors confirmed on June 27 that Chemours was storing the wastewater in tanks for off-site incineration.31

Test results announced July 14, 2017, found concentrations of GenX at several test sites to be higher than the state’s new safety goal, though beginning to decline with Chemours having stopped discharging. Subsequent testing in July and August found sites falling below the safety goal of 140 ng/L except at the Chemours site itself. On August 24, 2017, DEQ tests found all sites below the safety goal.32

Does the state’s regulatory authority hinge on EPA acting on GenX first?

On July 17, 2017, Gov. Roy Cooper sent a letter to Scott Pruitt, the administrator of the EPA, requesting that agency take actions regarding GenX. Cooper requested the EPA to “move more quickly to finalize its health assessment of GenX and set a maximum contaminant level for it.”33

The stated reason for this request made it seem as if the state were legally unable to force Chemours to limit its discharge of GenX and other contaminants unless the EPA acted first: “These are critical steps that must take place in order for North Carolina to be able to require Chemours to limit or eliminate discharge of GenX.” [Cooper letter, emphasis added]

Later, Gov. Cooper referenced the EPA’s 2009 consent order with Chemours under the Toxic Substances Control Act that limited the company’s emissions from GenX production. Gov. Cooper requested the EPA amend the order to include “any and all release of GenX,” including as a byproduct, and again with the implication that without the EPA taking that action, North Carolina would lack the authority to regulate GenX and other contaminants.34

But were Cooper’s assertions accurate? Joel A. Mintz, a former chief attorney with the EPA who teaches environmental law and enforcement at the Shepherd Broad College of Law at Nova Southeastern University in Florida, pointed out to StarNews that under the Clean Water Act, “any discharge of a pollutant to navigable waters is prohibited unless it is specifically allowed in a permit.”35

Mintz’s comments were in line with CFPUA’s requests to DEQ in their June 19 letter. He said, “If Chemours did not report that it was discharging GenX in its National Pollution Discharge Elimination System permit application, and the state did not establish any effluent limitations for it, any discharge of GenX by Chemours is potentially a violation of the Clean Water Act that can be subject to an enforcement action by the state.”36

On July 24, 2017, the legal counsel for CFPUA sent a seven-page letter to DEQ Secretary Regan with a detailed discussion of “the State of North Carolina’s authority and duty” to prohibit discharge of GenX and other pollutants and to require 100 percent removal from Chemours wastewater discharge. The letter, which addressed Chemours’ pending request for permit reissuance, delved into state statutes concerning such pollutants as “other wastes” and “[d]eleterious substances.” It also held that, given that Chemours announced it would remove 100 percent of GenX from its Fayetteville Works plant, a 100 percent removal standard therefore met the state definition as “practical.”37

In short, the CFPUA letter disagreed with DEQ on several key areas. Specifically, CFPUA lawyers made clear that, as GenX and other pollutants meet all the statutory standards for regulation, the state therefore has the authority and duty to condition permitting based on prohibiting discharge and requiring 100 percent removal.

On July 24, 2017, Gov. Cooper issued a directive to the State Bureau of Investigation’s Diversion and Environmental Crimes Unit to “assess whether a criminal investigation is warranted” from Chemours’ discharge of GenX into the Cape Fear River.38

On July 28, 2017, using the Clean Water Act’s citizen suit provision, the Civitas Institute sent a 60-day notice letter to Chemours to notify the company of Civitas’ intent to sue to enforce the provisions of the Clean Water Act with respect to the “unlawful discharge of industrial waste — GenX” in the Cape Fear River Basin without “requisite authorization under the NDPES [National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System] program.” Civitas cited North Carolina rules implementing the Clean Water Act under which “discharge of these compounds is likely a violation of water quality standards.” Copies of the letter were sent to DEQ and the EPA.39

On August 3, 2017, CFPUA likewise sent a 60-day notice letter of intent to sue Chemours and its parent company, DuPont. The letter, which was also sent to the officials at EPA and DEQ, Gov. Cooper, N.C. Attorney General Josh Stein, and U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, gave a highly detailed account of the history of the GenX and its discharge. It included again a section on “violations of North Carolina water quality standards adopted and enforced pursuant to the Clean Water Act, including water quality standards for ‘oils, deleterious substances, colored, or other wastes,’ 15A NCAC 2B .0211(12), and for ‘toxic substances.’ 15A NCAC 2B .0208,15A NCAC 2B .0211 (incorporating 15A NCAC 2B .0208 by reference), and 15A NCAC 2B .0216(3)(a) and (h).”40

That same day, news broke that the U.S. Attorney’s office in the Eastern District of North Carolina had launched a federal investigation into the matter. The StarNews reported that federal investigators had issued a criminal subpoena to DEQ on July 28, 2017 seeking by Aug. 22, 2017 that DEQ “provide to a Wilmington grand jury permits, environmental compliance information, reports and correspondence about Chemours’ Fayetteville Works facility, GenX and other fluorinated chemicals.”41

What exactly is the U.S. Attorney’s office investigating?

That’s a good question. The information reportedly sought by the federal investigation would appear moot, however, if Chemours’ compliance was as readily apparent as public statements by DEQ officials made it sound.

When did the General Assembly get involved, and how did legislators respond?

On August 8, 2017, DEQ Secretary Regan and DHHS Secretary Mandy Cohen sent a letter to legislators asking for an “emergency appropriation” of over $2.5 million to DEQ and DHHS to address the discharge of GenX and other pollutants in the Cape Fear River. According to the department heads, “recent budget cuts and the large scope and pressing nature of this challenge require your help.” Their requested funds would create new positions in both departments, create a new unit in the DHHS, and fund water sampling by DEQ.42

The next day, legislators sent a letter to Gov. Cooper in response, asking several questions seeking clarification on what they called “multiple inconsistencies in your administration’s handling of the crisis” and “what looks like a reversal of course on several fronts.” Key information legislators sought included:

- When anyone in the administration first discussed GenX with Chemours

- If DEQ ever knew or approved of the GenX discharge, given DEQ’s statement that Chemours had identified their discharge of GenX in all permit applications

- What the governor requested SBI to investigate, since the DEQ head had publicly stated Chemours had not broken the law

- Why within a month DHHS dropped its health goal for GenX by a factor of 500

- If the governor was aware that DEQ doesn’t need additional EPA action to regulate GenX and already regulates several compounds without EPA standards

- If the governor’s office or other executive branch agencies also received a federal criminal subpoena from the U.S. Attorney’s Office, as DEQ did

- If the administration would be transparent and share all public documents submitted in response to those subpoenas

- Why DEQ had not sent Chemours a Notice of Violation under the Clean Water Act43

The letter also sought information about the funding requested, including how the additional funds would affect discharge into the Cape Fear River, given that Chemours had already announced it was ceasing it, and if DEQ and DHHS required taxpayer funding for additional staffing positions given their many nonregulatory positions that could be shifted to help out.

Secretaries Regan and Cohen responded on August 14. Their letter acknowledged the state’s authority to regulate the compounds without EPA action, but they claimed a current “lack of sufficient research at the state or federal level to make these determinations for GenX and other unregulated compounds,” later stating that “making these determinations requires scientific studies, and experts to do it.” They reiterated their request for funding for more staff, stating that water quality positions had been cut since 2013.44

The letter also claimed that “the state was successful at stopping Chemours from releasing GenX into the Cape Fear River Basin.”45

What happened at the legislature’s Environmental Resource Commission hearing in Wilmington?

On August 18, 2017, the legislative oversight commission for the environment, the Environmental Review Commission, announced it would hold a public hearing August 23 to “learn about the presence of the GenX compound in the Cape Fear River and its impacts on regional drinking water supplies, and associated regulatory issues.” The Environmental Review Commission chose to meet not in Raleigh, but in Wilmington, to tour facilities and also to receive public comment from local citizens in the affected areas.46

At that August 23 hearing, UNC-Wilmington professor of marine biology Larry Cahoon discussed the problems of GenX and many other related unregulated compounds, their poor reaction with the human body (especially the liver, ovaries, and testes), how little there is known about them, and the failure of most water treatment processes to remove them.47

Cahoon was asked by Sen. Dan Bishop (R-Mecklenburg) why he disagreed with Secretary Regan’s statement that Chemours was not breaking law, to which Cahoon responded that, having seen the permits, he had seen no evidence that Chemours’ discharge had been properly disclosed and properly permitted. Cahoon stated he hadn’t been “satisfied that the level of technical expertise [in DEQ] is sufficient” to evaluate the risk of GenX and related compounds.48

Sen. Bishop asked, “Given then what you have seen, do you have any insight at all into how DEQ came to the conclusion the company [Chemours] was not in violation of the law?” Cahoon responded, “I have no idea how they got to that point.”49

Sen. Erica D. Smith (D-Bertie) asked Cahoon that, in light of relative uncertainty and ongoing need for further research into these chemicals, what exactly was the law being broken by Chemours, to which he responded that Chemours knew that the chemical compounds were toxic and were in the discharge higher than their permitted levels, which was a failure to disclose. With respect to enforcement, he said it was a Clean Water Act and safe drinking water matter, not a Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) issue, because TSCA relates to production, not discharge.50

Secretaries Regan and Cohen also spoke at the hearing. Regan continued to press the administration’s case for more funding for new staff positions and to focus on testing and permits, for which there is a backlog.51

Rep. Chris Millis (R-Onslow) said he was concerned about the Clean Water Act’s shielding provision in light of Secretary Regan’s comment that the company had not broken the law, and asked, “Do you and your staff believe the Chemours did not break the law?”52

Secretary Regan said that comment was “a snapshot,” that “at that moment, because we were at the beginning effort, I did not have any evidence that there was any illegal activity and that there had been any compromise of their permit.”53

In a follow-up question, Millis asked, “From where you were to where you are today, why has there not been a Notice of Violation issued to Chemours to the fact that they have broken the law?” Secretary Regan answered they needed to be “very, very thorough” to avoid “missteps” and “get this right” because it is a complex issue.54

Sen. Bishop asked DHHS Secretary Cohen about the information DHHS used to change their health goal for GenX, which was based on proprietary data not available to the public. Secretary Cohen stated that they are proprietary business studies shared with the EPA, animal studies (not human studies), but studies that need to remain proprietary. Sen. Bishop asked why such impactful information needed to remain proprietary. Secretary Regan said the agencies’ access to it was due to the 2009 consent order between the EPA and DuPont, and that they were still seeking access to confidential information.55

Sen. Bishop asked Secretary Regan that because that information “had the sort of impact on Sec. Cohen’s conclusion about risk, why don’t you have enough information to issue a Notice of Violation to the company [Chemours] based on that?”56

Secretary Regan said DEQ was “gaining access to that information” and that it was “very important that we get our hands on all of this information so we can develop the complete picture as we start looking at whether this company has done anything in terms of a violation.”57

What does House Bill 56/Session Law 2017-209 do, and why did Gov. Cooper veto it?

On August 28, 2017, the EPA alerted DEQ that scientists had found two new GenX-related chemicals, called “Nafion byproducts 1 and 2,” and three other unregulated compounds in wastewater discharged by Chemours into the Cape Fear River.58The DHHS announced this news on August 31. CFPUA immediately called for DEQ to modify or revoke Chemours’ permit.59

The day before, on August 30, the state Senate and House had received a conference committee substitute of House Bill 56, which added a new section for “GenX Response Measures.” The General Assembly included its statement of finding in the legislation that the discharge of GenX in the Cape Fear River “demonstrates the need for supplemental funding for impacted local public utilities for the monitoring and treatment of GenX and to support the identification and characterization by scientists, engineers, and other professionals of GenX in the Cape Fear River.”60

The new version was adopted by the Senate in special session on August 30 and the House on August 31, and the ratified bill with the new section was sent to the governor that same day.61 Legislative leaders called the supplemental funding just a start.62

The new section had four main provisions:

- $185,000 to the CFPUA to find and use new water treatment technology for removing GenX from the water supply and to continue monitoring water supplies from the Cape Fear River.

- $225,000 to UNC-Wilmington for scientific studies of where, how much, and how highly concentrated is GenX in the Cape Fear River, issues of GenX biodegradation or bioaccumulation, and GenX’s risks posed to human health.

- Requiring the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory at UNC-Chapel Hill to create (1) a publicly available, searchable online database of National Pollution Discharge Elimination System and other water quality permits, permit applications, and relevant supporting documents, and (2) an electronic system for filing permit applications and other supporting documents.

- Demanding a detailed written report from DEQ to the Environment Review Commission of the General Assembly on September 8, 2017, to explain why DEQ had not issued a Notice of Violation to “any company or individual that has discharged GenX to the Cape Fear River,” if by that date DEQ had still not issued a Notice of Violation.63

A few other provisions in H.B. 56 included adding some exemptions to river buffer rules for public safety purposes or walking trails, establishing a Coastal Storm Damage Mitigation Fund, making additional requirements for Catawba River water quality testing, allowing more competition in counties’ solid waste management, and repealing a prohibition against retailers in Outer Banks counties from using plastic bags and paper bags composed of less than 40 percent recycled paper.64

Gov. Cooper waited three weeks to act on the bill, vetoing it on September 21. His primary objection to the bill was that it “fails to appropriate any needed funds” to DEQ and DHHS regarding discharges of GenX and other compounds. He also objected that it “weakens protections from river pollution and landfills and repeals a local plastic bag ban.”65

What happened in the three weeks in between when legislators passed H.B. 56 and the governor vetoed it?

Upon passing the legislation, DEQ suddenly assumed a more vigorous approach. A WRAL report on September 6, 2017, noted “a shift in the way DEQ had been handling this issue.”66 Attorney Joel Mintz described it as a “dramatic shift” in the DEQ’s attitude.67

“Rather than persist in its passive toleration of the company’s pollution, the department began to exercise its enforcement authority in a more vigorous manner,” Mintz wrote.68

Here is how that shift looked. On September 5, DEQ issued Chemours a 60-day notice of intent to suspend its permit. DEQ cited its statutory authority to take such an action. DEQ stated there was “sufficient cause” to suspend the permit and “no evidence in the permit file indicating that Chemours or DuPont (Chemours’ predecessor) disclosed the discharge to surface water of GenX compounds at the Fayetteville Works.”69

DEQ’s letter gave Chemours till the date of September 8, 2017 to cease discharge of GenX-like compounds (Nafion byproducts 1 and 2). It also demanded Chemours continue to prevent GenX discharge, cease discharge of any other similar compounds by October 20, 2017, and comply with all unmet requests for information from DEQ.70

The next day, DEQ issued a Notice of Violation against Chemours based on groundwater testing results from early August.71

The day after that, DEQ filed a comprehensive complaint in Superior Court in Bladen County alleging a wide range of violations by Chemours, including that the company had failed to disclose its discharges as required under the Clean Water Act. DEQ’s suit detailed its authority to regulate the discharged compounds despite a lack of EPA standards and attested to the fact that the 2009 consent order Chemours had with the EPA under TSCA does not shield the company from unlawful discharges under the Clean Water Act. 72

Two weeks later, on September 20, DEQ demanded Chemours provide five years of data concerning “as to whether GenX and other emerging contaminants are currently, or have been, emitted as an air contaminant.”73

The next day (September 21) featured Cooper’s veto, which the General Assembly overrode on October 4, 2017.74

Conclusion

The issue is still ongoing. DEQ has issued three more Notice of Violations against Chemours between November 2017 and June 2018.75 DEQ also threatened to revoke Chemours’ air permit in April, which the company called “arbitrary and capricious” and made without regard for Chemours’ investing in new abatement technologies worth over $100 million to eliminate nearly all emissions by 2020.76 Chemours also invited reporters to tour their facility and held a town hall with concerned citizens.77

Gov. Cooper’s 2018 budget proposal sought $14.5 million in GenX-related items: $7 million for new staff at DEQ; $536,000 for new staff at DHHS; $2.5 million to upgrade DEQ’s Reedy Creek Laboratory and add equipment and staff; and $4.4 million to DEQ for online permit tracking and access.78

The General Assembly passed a state budget that included nearly $10 million in GenX-related items. Of that, $3.5 million was new spending: $1 million to the NC Policy Collaboratory at UNC-Chapel Hill for water sampling and analysis for GenX and related compounds and for addressing permit matters;79 $2 million for a PFAS Recovery Fund in the Division of Water Infrastructure of DEQ to provide grants-in-aid to local governments; $450,000 to the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority for sampling, testing, and treatment costs. Another $6.4 million of that is redirected from existing appropriations, including: $5 million to the NC Policy Collaboratory at UNC-Chapel Hill to address GenX and related compounds in state watersheds; $1.4 to DEQ to support water and atmospheric sampling and analysis for GenX and related compounds, staffing and operational support sampling and analysis, and staffing and support to address permit backlogs.80

The General Assembly also added new state laws to authorize the governor to order a facility to cease operation for unauthorized release of GenX and related compounds and to direct the DEQ to order a company responsible for contaminating private drinking wells with GenX and related compounds to establish permanent replacement water supplies for the affected well owners.81

Endnotes

1. “GenX Health Information.” North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services: Division of Public Health, September 2017.; Way, Dan. “EPA confirms GenX-related compounds used in solar panels.” Carolina Journal, August 27, 2018.

2. Otterbourg, Ken. “Teflon’s River of Fear.” Fortune, May 24, 2018.; Hagerty, Vaughn. “Previous contamination led to EPA fine, $671 million settlement.” StarNews, June 7, 2017.

3. Ibid.

4. Otterbourg, op. cit.

5. Dukes, Tyler, Laura Leslie, Travis Fain, and Candace Sweat. “Timeline: Tracking GenX Contamination in NC.” WRAL, August 17, 2017.

6. Otterbourg, op. cit.

7. Otterbourg, op. cit.; Adams, Jennifer H., and Robin Smith. “CFPUA GenX Timeline Investigation.” Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, June 20, 2017.

8. Sun, Mei, Elisa Arevalo, Mark Strynar, Andrew Lindstrom, Michael Richardson, Ben Kearns, Adam Pickett, Chris Smith, and Detlef R. U. Knappe. “Legacy and Emerging Perfluoroalkyl Substances Are Important Drinking Water Contaminants in the Cape Fear River Watershed of North Carolina.” Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2016 3 (12), 415-419, DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00398.

9. Adams and Smith, op. cit.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.; Dukes et al., op. cit.

14. “Full DEQ Interview,” WBTV, September 1, 2017. (starting at the 9:45 mark).

15. Cf. Hagerty, Vaughn. “Toxin taints CFPUA drinking water.” StarNews, June 7, 2017.

16. WBTV, op. cit.

17. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NC DHHS). “Questions and Answers Regarding North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services Updated Risk Assessment for GenX (Perfluoro-2-propozypropaoic acid).” July 14, 2017.

18. Dukes et al., op. cit.

19. NC DHHS “Questions and Answers,” op. cit.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. NC DHHS. “N.C. DHHS Releases Summary of Selected Cancer Rates for Counties in Cape Fear Region.” Press release, June 29, 2017.

23. Hagerty, Vaughn. “Did Chemours Tell NC It Was Discharging GenX?” StarNews, June 29, 2017.

24. Ibid.; cf. Dukes et al., op. cit.

25. Hagerty, “Did Chemours Tell NC,” op. cit.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. House, George W. and V. Randall Tinsley. George W. House and V. Randall Tinsley to Secretary Regan, June 19, 2017. “GenX in the Cape Fear River; First Set of Requests for DEQ Action.”

29. Ibid., citing North Carolina General Statutes, § 143-215.1(b)(2).

30. Dukes et al., op. cit.

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. Cooper, Governor Roy. Letter to Mr. E. Scott Pruitt, Washington, DC, July 17, 2017.

34. Ibid.

35. Hagerty, Vaughn. “Concerns about DuPont’s Discharge Raised in 2002.” StarNews, July 26, 2017.

36. Ibid.

37. House, George W., V. Randall Tinsley, and Joseph A. Ponzi. “GenX Pollutants in the Cape Fear River Are Not Unregulated Substances, Allowable Concentration in Cape Fear River Is Zero (or Non-Detectable), 100% Removal Required for Chemours Wastewater Discharge.” Letter to Secretary Michael Regan, June 24, 2017.

38. Cooper, Governor Roy. “Memo: Water Quality State Action Items.” Press release, Office of North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper, July 24, 2017.

39. De Luca, Francis. “Civitas Sends Letter to Enforce Provisions of the Clean Water Act.” Civitas Institute, August 2, 2017.

40. House, George W., V. Randall Tinsley, and Joseph A. Ponzi. George W. House, V. Randall Tinsley, and Joseph A. Ponzi to E.I. de Pont de Nemours and Company, Ellis H. McGaughy, V. Anne Heard, Michael S. Regan, Michael Scott, Josh Stein, The Chemours Company, Scott Pruitt, Jeff Sessions, S. Jay Zimmerman, Governor Roy Cooper, August 3, 2017.

41. Maurer, Kevin, and Vaughn Hagerty. “Feds, CFPUA Go on Legal Offensive over GenX.” StarNews, August 3, 2017.

42. Regan, Secretary Michael and Secretary Mandy Cohen. Letter to The Honorable Ted Davis (inter alia), Raleigh, NC, August 8, 2017.

43. Cook, Senator Bill, Senator Rick Gunn, Senator Michael Lee, Senator Bill Rabon, Senator Norm Sanderson, Senator Trudy Wade, and Senator Andy Wells. Letter to Governor Roy Cooper. August 9, 2017.

44. Regan, Secretary Michael and Secretary Mandy Cohen. Letter to The Honorable Bill Cook (inter alia), Raleigh, NC, August 14, 2017.

45. Ibid.

46. Wade, Senator Trudy L., Representative James W. Dixon, and Representative Charles Worden McGrady. “Meeting Notice.” E-mail message to Members of Environmental Review Commission, August 8, 2017.

47. Final minutes. Environmental Review Commission, Andre Mallette Training Center, Human Resources Suite New Hanover County Government Center, Wilmington, NC, August 23, 2017.

48. Audio of Environmental Review Commission, Andre Mallette Training Center, Human Resources Suite New Hanover County Government Center, Wilmington, NC, August 23, 2017, about the 1:27:00 mark.

49. Ibid., about the 1:28:00 mark.

50. Ibid., about the 1:41:00 mark.

51. Final minutes, ERC, op. cit.

52. Audio, ERC, op. cit., about the 2:05:00 mark.

53. Ibid., about the 2:06:00 mark.

54. Ibid., about the 2:07:00 mark.

55. Ibid., about the 2:19:00 mark.

56. Ibid., about the 2:26:00 mark.

57. Ibid., about the 2:26:00 mark.

58. “State Seeks to Stop Additional Chemical Discharges into the Cape Fear River,” press release, NC DHHS, August 31, 2017.

59. [House, George W., V. Randall Tinsley, and Joseph A. Ponzi. “Request for Permit Revocation.” Letter to Secretary Michael S. Regan and Director S. Jay Zimmerman, August 31, 2017.

60. “House Bill 56 / SL 2017-209,” North Carolina General Assembly. 2017.

61. “House Passes GenX Funding, Repeals Plastic Bag Ban, Goes Home.” Carolina Journal, August 31, 2017.

62. Fain, Travis. “GOP ties GenX funding to plastic bag ban repeal.” WRAL, August 31, 2017.

63. H.B. 56, op. cit.

64. Ibid.

65. Cooper, Governor Roy. “Governor Roy Cooper Objections and Veto Message: House Bill 56, An Act to Amend Various Environmental Laws.” September 21, 2017.

66. Fain, Travis. “State Issues Notice of Violation to Chemours.” WRAL, September 6, 2017.

67. Mintz, Joel. “North Carolina v. Chemours: Early Reflections on an Ongoing State Environmental Enforcement Case.” CPRBlog, The Center for Progressive Reform, November 17, 2017.

68. Ibid.

69. Zimmerman, Director S. Jay. Lettter to Mr. Ellis H. McGaughy, Fayetteville, NC, September 5, 2017.

70. Ibid.

71. “State issues notice of violation against Chemours based on new groundwater tests,” press release, North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, September 6, 2017.

72. State of North Carolina, ex rel., Michael S. Regan, Secretary, North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality v. The Chemours Company FC, LLC, 2017.

73. Abraczinskas, Director Michael A. Letter to Mr. Ellis H. McGaughy, Fayetteville, NC, September 20, 2017.

74. H.B. 56, op. cit.

75. “GenX Investigation: Investigation and Enforcement Actions.” DEQ, accessed September 6, 2018.

76. Goss., Joel M. Goss. Letter to William F. Lane and Michael A. Abraczinskas, Raleigh, NC, April 27, 2018.

77. Dukes et al., op. cit.; Wagner, Adam. “What’s happened since we first learned of GenX a year ago? A lot.” StarNews, June 8, 2018.

78. Burns, Matthew. “Cooper seeking $14.5 million in state budget to address GenX.” WRAL, April 10, 2018.

79. “The Joint Conference Committee Report on the Base and Expansion Budget for Senate Bill 99.” North Carolina General Assembly, May 28, 2018, p. D 8.

80. Senate Bill 99/S.L. 2018-5. See Section 13.1.