In North Carolina, occupational regulation tends to be an all-or-nothing thing. Either the state applies the most extreme form of regulation (licensing), or it mostly leaves the occupation alone.

This approach means North Carolina licenses more occupations than most states. It also means that when industry interest groups go to the legislature to address problems in their field of labor, they often ask for licensure to address them. It seems like the only way.

Finally, it means state occupational licensing boards are at risk of federal antitrust violations, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission (2015).1

This paper calls for an overhaul of North Carolina’s approach toward occupational regulation. It argues for reforming occupational licensing for several reasons: legal, practical, and feasible.

Reform is a legal necessity

By design, licensing blocks people from simply entering their chosen field of labor. Only those who cross all the hurdles to get a license can ply their trade.

Those hurdles can include licensing fees, school tuition and fees to obtain mandatory credentials or continuing education credits, sitting fees for qualifying exams, time spent gaining experience, time spent studying for classes and qualifying exams, opportunity costs of forgone work, and also satisfying licensing boards’ criminal background checks and “good moral character” requirements.

A constitutional right

This entry regulation is a problem because North Carolina recognizes a constitutional right of people to enjoy the fruits of their own labor. The language lifts from the Declaration of Independence, but it adds the labor clause and is inscribed in the state constitution:

Section 1. The equality and rights of persons: We hold it to be self-evident that all persons are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, the enjoyment of the fruits of their own labor, and the pursuit of happiness.2 (Emphasis added.)

A federal fight

In its 2015 ruling against the N.C. Board of Dental Examiners, the U.S. Supreme Court dismantled a long-held presumption: that state occupational licensing boards are automatically immune from federal antitrust laws.

In the court’s opinion, a state licensing board may violate federal antitrust law if a controlling number of board members comprise “active market participants” regulated by the board but the board is not actively supervised by the state.3

It is not clear how the state could demonstrate active supervision over licensing boards. If the state were to free more occupations from the highly restrictive, all-or-nothing approach of licensing, however, that would eliminate anticompetitive concerns at their root.

An ongoing federal fight

Meanwhile, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has a new Economic Liberty Task Force to focus on state occupational licensing activities.4 Acting FTC chairman Maureen Ohlhausen announced it in a March 31 speech at George Mason Law Review’s antitrust symposium.5

Primarily, the FTC’s interest in economic liberty will be advocacy and partnership. Ohlhausen is not averse to enforcement actions, however. State policymakers should take heed that the North Carolina Dental court case is considered “Ohlhausen’s greatest achievement so far as an FTC commissioner,” in the words of a January 2017 Reason magazine profile.6

As Ohlhausen told the antitrust symposium:

Of course, in some instances enforcement may be an appropriate tool, consistent with the Supreme Court’s ruling in North Carolina Dental and other state action cases. This is particularly the case when the “Brother, May I?” problem exists. Active market participants still control many state boards that impose licensing restrictions. Thus, the question revolves around whether the state is actively supervising the board actions that displace competition. When warranted, the FTC will bring enforcement actions in appropriate cases.7 (Emphasis added.)

In its assessment, The National Law Review expects there will be “an increase in FTC actions involving licensing boards.”8 It counsels:

Licensing boards and those who are involved in licensing regulations should examine the ways in which the regulation affects or could affect competition, whether there is evidence that a regulation is necessary to achieve the targeted policy goal, whether the regulation is narrowly tailored to meet the policy goal, and whether a less restrictive alternative is available to achieve the policy goal and benefit competition.9 (Emphasis added.)

Right now, North Carolina’s approach to occupational regulation is too heavy-handed to meet these criteria. Leaving aside how state licensing could affect competition, North Carolina’s approach is not geared for keeping occupational regulation narrowly tailored to the policy issue at hand, nor to seek less restrictive alternatives to achieve the same goal.

In July, U.S. Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta spoke to a gathering of state legislators about the need to reform occupational licensing. Citing that “more than one in four Americans need a license to legally perform their work,” Acosta warned legislators about the problems of “excess licensing” and “using licensing to limit competition, bar entry, or create a privileged class.”10

Acosta then urged legislators to limit licensing to only where it is clearly necessary to address compelling health and safety concerns and streamline them to only the extent needed:

The Trump administration is committed to working with you to strengthen our economy and empower the American workforce. Americans want principled, broad-based reform.

If licenses are unnecessary, eliminate them.

If they are needed, streamline them.

And, if they are honored by one state, consider honoring them in your own state.11

State leaders should know that the Trump administration is building on reform efforts started under the Obama administration.12 The federal government’s interest in state occupational licensing reform doesn’t appear to be a passing fancy.

A broader approach is a practical need

The General Assembly regularly receives requests from occupations seeking special validation. The 2017 session, which was typical, saw bills filed that would:

- Establish new licensing boards for naturopathic doctors13 and music therapists14

- Forbid hospitals from hiring uncredentialed surgical technologists15

- Require insurers to pay for autism treatment by certified behavioral analysts16

- Allow (for a fee) a special endorsement to a respiratory care practitioner’s license to recognize outside training and credentialing beyond requirements for licensure17

- Allow (for a fee) voluntary registration of certified interior designers within the N.C. Department of Insurance18

Note that not all of those bills pertain to licensing. The range and frequency of such bills year after year19 strongly suggest there is a need for a better approach.

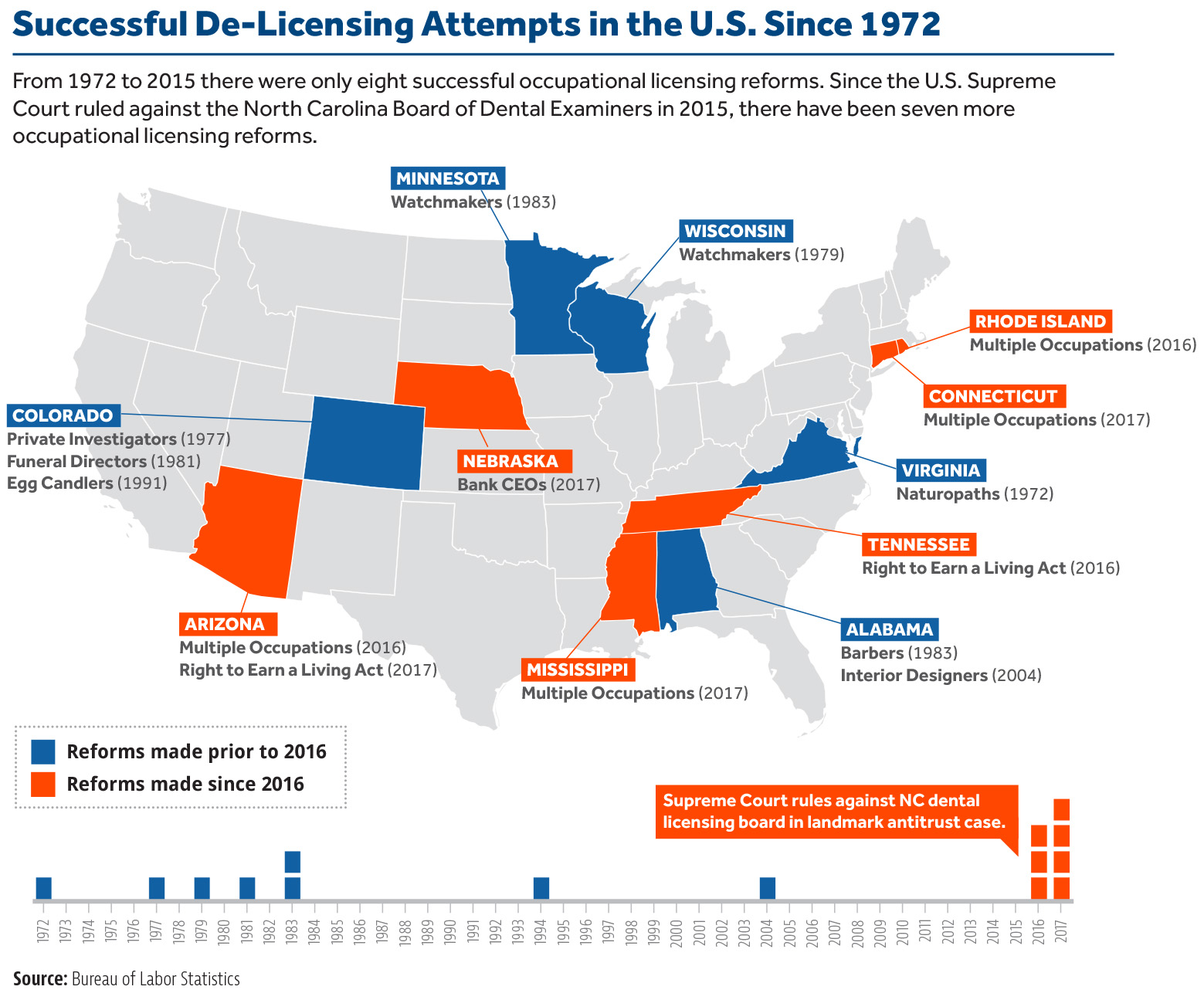

Finding such a balance has historically been difficult. For decades, nearly every attempt across the nation to free occupations from highly restrictive state licensing failed.

In May 2015, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics published a review of the previous four decades’ worth of de-licensing efforts. It found “only eight instances of the de-licensing of occupations over the past 40 years.”20 Only eight successes in 50 states over 40 years.

In just the past year, however, seven new de-licensing attempts have succeeded. As suggested above, the political landscape has changed.

Since 2016, several states have succeeded in occupational licensing reforms. Those reforms can be put in two categories: removing certain required state licenses and changing the state’s entire approach to occupational regulations.

States removing certain occupational licenses:

- Arizona, 2016: Gov. Doug Ducey signed a bill to exempt four occupations from licensing requirements.21

- Rhode Island, 2016: Gov. Gina M.

Raimondo eliminated 27 licenses identified by the Office of Regulatory Reform in collaboration with state licensing agencies as part of the 2016 budget.22 - Nebraska, 2017: Gov. Pete Ricketts signed a package of bills that, among other things, let state banks and credit unions opt out of the requirement that officers hold a state bank executive officer license.23

- Connecticut, 2017: Gov. Dannel Malloy signed Senate Bill 191, which eliminated licenses that did not have educational or training requirements: swimming pool builders, swimming pool maintenance and repair, shorthand reporters, and itinerant vendors. It also eliminated athlete agents’ registration and liquor wholesalers’ salesmen certification.24

States revamping their entire approach to occupational regulations:

- Tennessee, 2016: Gov. Bill Haslam signed the Right to Earn a Living Act, which limits entry regulations into an occupation (i.e., licensing) to only those that are legitimately necessary to protect public health, safety, or welfare, and when those objectives could not be met with less burdensome means, including certification, bonding, insurance, inspections, etc.25

- Arizona, 2017: Gov. Doug Ducey signed State Bill 1437 into law, as Arizona joined Tennessee in passing the Right to Earn a Living Act.26 Ducey also issued an executive order that all state licensing boards report their minimum requirements and be required to justify any that exceed national averages.27

- Mississippi, 2017: Gov. Phil Bryant signed House Bill 1425, a far-reaching reform of state occupational licensing. The new law puts the governor, secretary of state, and state attorney general in an active supervising role over existing state occupational licensing boards. Going further, the law creates alternative structures to licensure for professions — private certification, third-party reviews, fraud protection, inspections, bonding, insurance, etc. — that must be proven lacking before seeking to expand into licensure.28

Conclusion and recommendations

After decades of occupational licensing being nearly untouchable in state governments, several states have very recently made sweeping reforms. It’s not an aberration. Those states show that modernizing a state’s approach to regulating occupations, including getting rid of unnecessary licensing, is a winning idea.

Meanwhile, however, North Carolina risks being left shackled to an unwieldy, highly restrictive, and patently anticompetitive approach. The risk is not just being passed by states with more competitive labor practices. The risk is also from federal antitrust and other enforcement actions.

What should North Carolina policymakers do? Who is pointing the way?

- Tennessee and Arizona now both have Right to Work Acts

- Mississippi now offers an array of alternative structures to licensing

- The FTC seeks narrowly tailored occupational regulations and less restrictive alternatives to licensing to protect competition

Numerous industries in North Carolina come to the legislature each year with a range of concerns, most of which are unsuited for licensing even if they are legitimate concerns.

A more comprehensive, nimbler process

For all these reasons, North Carolina needs a Right to Work Act approach to occupational regulation:

- Principles that, first and foremost, protect competition and the constitutional right to work

- Narrowly tailored regulations to address a legitimate concern

- The least restrictive regulations necessary to address that concern

- An array of policy alternatives to licensing, depending upon the kind of concern

Placing state entry regulations on some people’s chosen fields of labor should be a regulation of last resort, reserved only for the most extreme regulatory concerns. A state that recognizes its people have a constitutional right to “the enjoyment of the fruits of their own labor” should be extra careful its laws don’t tread on that right.

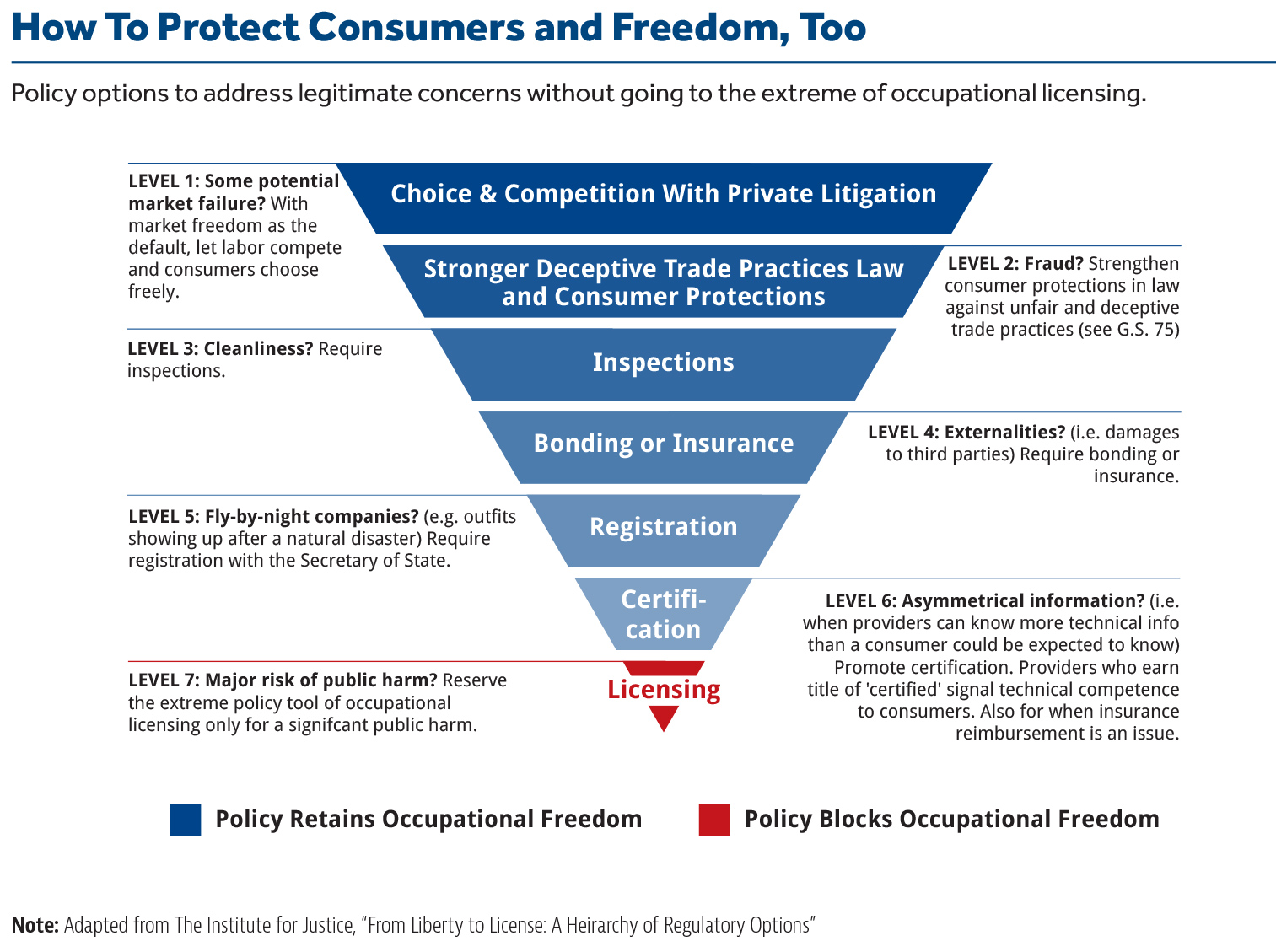

The state’s involvement in an occupation should be conformed to the legitimate issue at hand, and then go no further. What would that mean?

Matching regulation to concern

It means if there’s a significant concern about protecting consumers from fraud, then enhance the powers of the attorney general and the deceptive trade practices act.

If the significant concern is over cleanliness, then require inspections. If it’s damage to third parties, require bonding. If it’s shady, fly-by-night providers, require registration.

And if it’s insurance reimbursement or a knowledge imbalance, require certification.

Unlike licensing, none of those policies would preclude North Carolinians from enjoying their self-evident right to the enjoyment of their own labor.

APPENDIX A: Tennessee’s Right to Earn a Living Act

Following is the text of the Right to Earn a Living Act of Tennessee (Senate Bill 2469, 2015-2016 session of the General Assembly):

WHEREAS, the right of individuals to pursue a chosen business or profession, free from arbitrary or excessive government interference, is a fundamental civil right; and

WHEREAS, the freedom to earn an honest living traditionally has provided the surest means for economic mobility; and

WHEREAS, in recent years, many regulations of entry into businesses and professions have exceeded legitimate public purposes and have had the effect of arbitrarily limiting entry and reducing competition; and

WHEREAS, the burden of excessive regulation is borne most heavily by individuals outside the economic mainstream, for whom opportunities for economic advancement are curtailed; and

WHEREAS, it is in the public interest to ensure the right of all individuals to pursue legitimate entrepreneurial and professional opportunities to the limits of their talent and ambition; to provide the means for the vindication of this right; and to ensure that regulations of entry into businesses, professions, and occupations are demonstrably necessary and narrowly tailored to legitimate health, safety, and welfare objectives; now, therefore,

BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF TENNESSEE:

SECTION 1. This act shall be known and may be cited as the “Right to Earn a Living Act”.

SECTION 2. Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 4, Chapter 5, is amended by adding the following language as a new part:

4-5-501. As used in this part:

(1) “Entry regulation” means:

(A) Any rule promulgated by a licensing authority for the purpose of regulating an occupational or professional group, including, but not limited to, any rule prescribing qualifications or requirements for a person’s entry into, or continued participation in, any business, trade, profession, or occupation in this state; or

(B) Any policy or practice of a licensing authority that is established, adopted, or implemented by a licensing authority for the purpose of regulating an occupational or professional group, including, but not limited to, any policy or practice relating to the qualifications or requirements of a person’s entry into, or continued participation in, any business, trade, profession, or occupation in this state; and

(2) “Licensing authority” means any state regulatory board, commission, council, or committee in the executive branch of state government established by statute or rule that issues any license, certificate, registration, certification, permit, or other similar document for the purpose of entry into, or regulation of, any occupational or professional group. “Licensing authority” does not include any state regulatory board, commission, council, or committee that regulates a person under title 63 or title 68, chapter 11 or 140.

4-5-502.

(a)(1) No later than December 31, 2016, each licensing authority shall submit a copy of all existing or pending entry regulations pertaining to the licensing authority and an aggregate list of such entry regulations to the chairs of the government operations committees of the Senate and House of Representatives. The committees shall conduct a study of such entry regulations and may, at the committees’ discretion, conduct a hearing regarding the entry regulations submitted by any licensing authority. The committees shall issue a joint report regarding the committees’ findings and recommendations to the General Assembly no later than January 1, 2018.

(2) After January 1, 2018, each licensing authority shall, prior to the next occurring hearing regarding the licensing authority held pursuant to § 4- 29-104, submit to the chairs of the government operations committees of the Senate and House of Representatives a copy of any entry regulation promulgated by or relating to the licensing authority after the date of the submission pursuant to subdivision (a)(1). The appropriate subcommittees of the government operations committees shall consider the licensing authority’s submission as part of the governmental entity review process and shall take any action relative to subsections (b)-(d) as a joint evaluation committee. Prior to each subsequent hearing held pursuant to § 4-29-104, the licensing authority shall submit any entry regulation promulgated or adopted after the submission for the previous hearing.

(3) In addition to the process established in subdivisions (a)(1) and (2), the chairs of the government operations committees of the Senate and House of Representatives may request that a licensing authority present specific entry regulations for the committees’ review pursuant to this section at any meeting of the committees.

(4) Notwithstanding this subsection (a), the governor or the commissioner of any department created pursuant to title 4, chapter 3, relative to a licensing authority attached to the commissioner’s department, may request the chairs of the government operations committees of the Senate and House of Representatives to review, at the committees’ discretion, specific entry regulations pursuant to this section.

(b) During a review of entry regulations pursuant to this section, the government operations committees shall consider whether:

(1) The entry regulations are required by state or federal law;

(2) The entry regulations are necessary to protect the public health, safety, or welfare;

(3) The purpose or effect of the entry regulations is to unnecessarily inhibit competition or arbitrarily deny entry into a business, trade, profession, or occupation;

(4) The intended purpose of the entry regulations could be accomplished by less restrictive or burdensome means; and

(5) The entry regulations are outside of the scope of the licensing authority’s statutory authority to promulgate or adopt entry regulations.

(c) The government operations committees may express the committees’ disapproval of an entry regulation promulgated or adopted by the licensing authority by voting to request that the licensing authority amend or repeal the entry regulation promulgated or adopted by the licensing authority if the committees determine during a review that the entry regulation:

(1) ls not required by state or federal law; and

(2)(A) Is unnecessary to protect the public health, safety, or welfare;

(B) Is for the purpose or has the effect of unnecessarily inhibiting competition;

(C) Arbitrarily denies entry into a business, trade, profession, or occupation;

(D) With respect to its intended purpose, could be accomplished by less restrictive or burdensome means, including, but not limited to, certification, registration, bonding or insurance, inspections, or an action under the Tennessee Consumer Protection Act of 1977, compiled in title 47, chapter 18, part 1; or

(E) Is outside of the scope of the licensing authority’s statutory authority to promulgate or adopt entry regulations.

(d)(1) Notice of the disapproval of an entry regulation promulgated or adopted by a licensing authority shall be posted by the secretary of state, to the administrative register on the secretary of state’s website, as soon as possible after the committee meeting in which such action was taken.

(2) If a licensing authority fails to initiate compliance with any recommendation of the government operations committees issued pursuant to subsection (c) within ninety (90) days of the issuance of the recommendation, or fails to comply with the request within a reasonable period of time, the committees may vote to request the General Assembly to suspend any or all of such licensing authority’s rulemaking authority for any reasonable period of time or with respect to any particular subject matter, by legislative enactment.

(e) Except as provided in subdivision (a)(2), for the purposes of reviewing any entry regulation of a licensing authority and making final recommendations under this section, the government operations committees may meet jointly or separately and, at the discretion of the chair of either committee, may form subcommittees for such purposes.

SECTION 3. This act shall take effect upon becoming a law, the public welfare requiring it.

APPENDIX B: Right to Earn a Living Act — model legislation

Following is the text of the model Right to Earn a Living Act by the Goldwater Institute (reprinted with permission).

Section 1. This Act may be referred to as the “Right to Earn a Living Act.”

Section 2. {Statement of Findings and Purposes.}

(A) The legislature hereby finds and declares that:

(1) The right of individuals to pursue a chosen business or profession, free from arbitrary or excessive government interference, is a fundamental civil right.

(2) The freedom to earn an honest living traditionally has provided the surest means for economic mobility.

(3) In recent years, many regulations of entry into businesses and professions have exceeded legitimate public purposes and have had the effect of arbitrarily limiting entry and reducing competition.

(4) The burden of excessive regulation is borne

most heavily by individuals outside the economic mainstream, for whom opportunities for economic advancement are curtailed.

(5) It is in the public interest:

(a) To ensure the right of all individuals to pursue legitimate entrepreneurial and professional opportunities to the limits of their talent and ambition;

(b) To provide the means for the vindication of this right; and

(c) To ensure that regulations of entry into businesses and professions are demonstrably necessary and carefully tailored to legitimate health, safety, and welfare objectives.

Section 3. {Definitions}.

(A) ”Agency” shall be broadly construed to include the state, all units of state government, any county, city, town, or political subdivision of this state, and any branch, department, division, office, or agency of state or local government.

(B) “Entry regulations” shall include any law, ordinance, regulation, rule, policy, fee, condition, test, permit, administrative practice, or other provision relating in a market, or the opportunity to engage in any occupation or profession.

(C) ”Public service restrictions” shall include any law, ordinance, regulation, rule, policy, fee, condition, test, permit, or other administrative practice, with or without the support of public subsidy and/or user fees.

(D) ”Welfare” shall be narrowly construed to encompass protection of members of the public against fraud or harm. This term shall not encompass the protection of existing businesses or agencies, whether publicly or privately owned, against competition.

(E) ”Subsidy” shall include taxes, grants, user fees or any other funds received by or on behalf of an agency.

Section 4. {Limitation on Entry Regulations.}

All entry regulations with respect to businesses and professions shall be limited to those demonstrably necessary and carefully tailored to fulfill legitimate public health, safety, or welfare objectives.

Section 5. {Limitation on Public Service Restrictions.}

All public service restrictions shall be limited to those demonstrably necessary and carefully tailored to fulfill legitimate public health, safety, or welfare objectives.

Section 6. {Elimination of Entry Regulations.}

(A) Within one year following enactment, every agency shall conduct a comprehensive review of all entry regulations within their jurisdictions, and for each such entry regulation it shall:

(1) Articulate with specificity the public health, safety, or welfare objective(s) served by the regulation, and

(2) Articulate the reason(s) why the regulation is necessary to serve the specified objective(s).

(B) To the extent the agency finds any regulation that does not satisfy the standard set forth in Section 4, it shall:

(1) Repeal the entry regulation or modify the entry regulation to conform with the standard of Section 4 if such action is not within the agency’s authority to do so; or

(2) Recommend to the legislature actions necessary to repeal or modify the entry regulation to conform to the standard of Section 4 if such action is not within the agency’s authority.

(C) Within 15 months following enactment, each agency shall report to the legislature on all actions taken to conform with this section.

Section 7. {Administrative proceedings}.

(A) Any person may petition any agency to repeal or modify any entry regulation into a business or profession within its jurisdiction.

(B) Within 90 days of a petition filed under (A) above, the agency shall either repeal the entry regulation, modify the regulation to achieve the standard set forth in Section 4, or state the basis on which it concludes the regulation conforms with the standard set forth in Section 4.

(C) Any person may petition any agency to repeal or modify a public service restriction within its jurisdiction.

(D) Within 90 days of a petition filed under (C) above, the agency shall state the basis on which it concludes the public service restriction conforms with the standard set forth in Section 5.

Section 8. {Enforcement.}

(A) Any time after 90 days following a petition filed pursuant to Section 6 that has not been favorably acted upon by the agency, the person(s) filing a petition challenging an entry regulation or public service restriction may file an action in a Court of general jurisdiction.

(B) With respect to the challenge of an entry regulation, the plaintiff(s) shall prevail if the Court finds by a preponderance of evidence that the challenged entry regulation on its face or in its effect burdens the creation of a business, the entry of a business into a particular market, or entry into a profession or occupation; and either

(1) That the challenged entry regulation is not demonstrably necessary and carefully tailored to fulfill legitimate public health, safety, or welfare objectives; or

(2) Where the challenged entry regulation is necessary to the legitimate public health, safety, or welfare objectives, such objectives can be effectively served by regulations less burdensome to economic opportunity.

(C) With respect to the challenge of a public service restriction, the plaintiff(s) shall prevail if the court finds by a preponderance of the evidence that on its face or in its effect either:

(1) That the challenged public service restriction is not demonstrably necessary and carefully tailored to fulfill legitimate public health, safety or welfare objectives; or

(2) Where the challenged public service restriction is necessary to fulfill legitimate public health, safety or welfare objectives, such objectives can be effectively served by restrictions that allow greater private participation.

(D) Upon a finding for the plaintiff(s), the Court shall enjoin further enforcement of the challenged entry regulation or public service restriction, and shall award reasonable attorney’s fees and costs to the plaintiff(s).

Section 9. {State preemption of inconsistent local laws}

(A) The right of individuals to pursue a chosen business or profession is a matter of statewide concern and is not subject to further inconsistent regulation by a county, city, town or other political subdivision of this state. This article preempts all inconsistent rules, regulations, codes, ordinances and other laws adopted by a county, city, town or other political subdivision of this state regarding the right of individuals to pursue a chosen business or profession.

Endnotes

1. See discussion at “North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. FTC,” 129 Harvard Law Review 371, November 10, 2015.

2. North Carolina State Constitution, Article I, Section 1.

3. See discussion at Eric M. Fraser, “Opinion analysis: No antitrust immunity for professional licensing boards,” SCOTUS blog, February 25, 2015.

4. See “Economic Liberty: Opening the doors to opportunity,” web page of the Federal Trade Commission.

5. Maureen K. Ohlhausen, “Advancing Economic Liberty,” remarks to George Mason Law Review’s 20th Annual Antitrust Symposium, February 23, 2017.

6. Damon Root, “A Free Market Friend at the FTC,” Reason, January 2017.

7. Ohlhausen, “Advancing Economic Liberty.”

8. “Occupational Licensing—Do We Need to Protect ‘the Public from Rogue Interior Designers Carpet-Bombing Living Rooms with Ugly Throw Pillows?’,” The National Law Review, March 9, 2017.

9. “Occupational Licensing,” The National Law Review.

10. “U.S. Secretary of Labor Acosta Addresses Occupational Licensing Reform,” press release, U.S. Department of Labor, July 21, 2017.

11. “Acosta Addresses Occupational Licensing Reform.”

12. See, e.g., “FACT SHEET: New Steps to Reduce Unnecessary Occupation Licenses that are Limiting Worker Mobility and Reducing Wages,” press release, Office of the White House Press Secretary, June 17, 2016.

13. House Bill 692, North Carolina General Assembly, 2017-18 session.

14. House Bill 192, North Carolina General Assembly, 2017-18 session.

15. House Bill 199, North Carolina General Assembly, 2017-18 session.

16. House Bill 307, North Carolina General Assembly, 2017-18 session.

17. House Bill 358, North Carolina General Assembly, 2017-18 session.

18. House Bill 590, North Carolina General Assembly, 2017-18 session.

19. See, e.g., the list of occupations seeking licensing and other state regulations in the 2011-12 session of the General Assembly, published in Jon Sanders, “Guild By Association,” Spotlight No. 427, John Locke Foundation, January 28, 2013.

20. Robert Thornton and Edward Timmons, “The de-licensing of occupations in the United States,” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2015.

21. House Bill 2613, State of Arizona, Fifty-second Legislature, Second Regular Session, 2016.

22. See “FY 2016 Interactive Budget,” Office of Management and Budget, State of Rhode Island, and Thomas Mulvaney, “Technical Amendments to Article 20 of the FY 2016 Appropriations Act (15-H-5900), memorandum, May 22, 2015.

23. See, e.g., “Gov. Ricketts Signs First Occupational Licensing Reforms,” press release, Office of Governor Pete Ricketts, March 30, 2017, and discussion at Sarah Curry, “Strong Jobs Nebraska: The 2017 Occupational Licensing Review,” Policy Brief, Platte Institute, July 11, 2017.

24. Senate Bill 191, Connecticut General Assembly, Session Year 2017. See discussion at Rek LeCounte, “Nutmeggers Crack Open Occupational Licensing Laws,” Institute for Justice, July 14, 2017.

25. Senate Bill 2469, Tennessee General Assembly, 2015-2016. See discussion at “How-To Guide: Right to Earn a Living Act,” Beacon Center of Tennessee and National Federation of Independent Business, December 14, 2016.

26. Senate Bill 1437, State of Arizona, Fifty-third Legislature, First Regular Session, 2017. See discussion at Jon Riches, “SB 1437, the Right to Earn a Living Act,” Goldwater Policy Update, Goldwater Institute, February 14, 2017.

27. Governor Douglas A. Ducey, “Internal Review of Training Requirements, Continuing Education, Fees, and Processes,” Executive Order 2017-03.

28. House Bill 1425, Mississippi Legislature, 2017 Regular Session. See discussion at Eric Boehm, “This Mississippi Bill Could Be the Beginning of the End of Occupational Licensing Cartels,” Reason, March 31, 2017.