Outdated zoning, rent controls, and other regulations are preventing people in high-demand urban settings from providing affordable housing arrangements, such as adding accessory dwelling units (ADUs) like granny flats and garages converted into living spaces. Restrictive zoning is also preventing developers from adding housing options to areas where they’re in most demand. These have unintended consequences, even affecting how people move about in cities.

John Hood recently touched on that in discussing North Carolinians’ transportation choices. Hood noted the inescapable fact that North Carolinians prefer cars. Beyond that, however, Hood had some suggestions for people worried about traffic congestion in urban areas.

It would be “far more productive,” Hood said, “to reduce the extent to which people enter vehicles of any kind in the first place, and how long they stay in them.” So does that mean top-down government policies to force people out of cars?

No, because those don’t work to make people better off. Instead, rethink government policies that have the unintended consequence of making people have to choose vehicles more frequently than they otherwise would. Hood writes:

That means rethinking zoning and other regulations that create artificial separation between where people live, work, and shop.

I’m not just talking about working from home, in other words, although policymakers ought to make sure they aren’t unnecessarily blocking people from setting up businesses in their homes, for example. I’m also talking about mixed-use developments. … As a free-market conservative, I don’t want the government to try to force mixed-used developments on unwilling sellers and buyers. But I also don’t want government to get in their way, as is now too often the case.

Relaxing zoning codes, minimum lot sizes, and other regulations would have another welcome benefit in North Carolina’s urbanizing areas: downward pressure on housing prices and rents. We have artificial restrictions on supply. Even if more-affluent North Carolinians are the ones most likely to buy downtown condos or rent in trendy high-rises, their decisions would free up other housing stock for other customers.

Recent zoning reforms are helping people in high-demand urban settings create some affordable housing arrangements. In 2018 Minneapolis became the first major city to eliminate single-family zoning and allow multiple dwelling units per residence. Oregon became the first state to do so in 2019. Also in 2019 California relaxed zoning rules allowing for ADUs like granny flats and garage units.

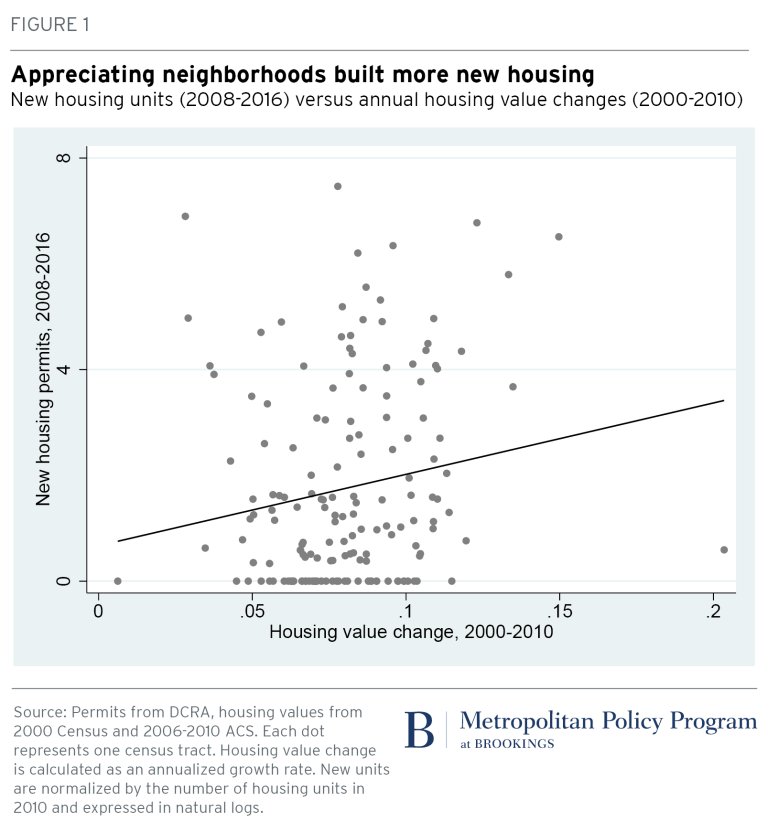

New research from the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings shows that restrictive zoning is doubly harmful to increasing housing options in high-demand urban areas. This study examined the impact of zoning regulations on housing supply in Washington, D.C. from 2000 to 2010:

A fundamental principle of economics is that when the price of goods or services increases, producers will increase supply. Therefore, when the price of housing in certain cities or neighborhoods increases, developers should build more homes. And indeed, District neighborhoods that saw higher growth in housing values did see more new housing construction—but only where restrictive zoning didn’t impede growth.

Home prices going up in an area while the housing stock is unchanged indicates that, yes, that area is in high demand. So people should be building more housing options in that area. And Brookings found just that:

Bringing new supplies would also have a downward effect on prices. That’s not to say they would decrease, because there are too many other factors at play, but additional supplies would keep prices from being as high as they would be without the new supplies.

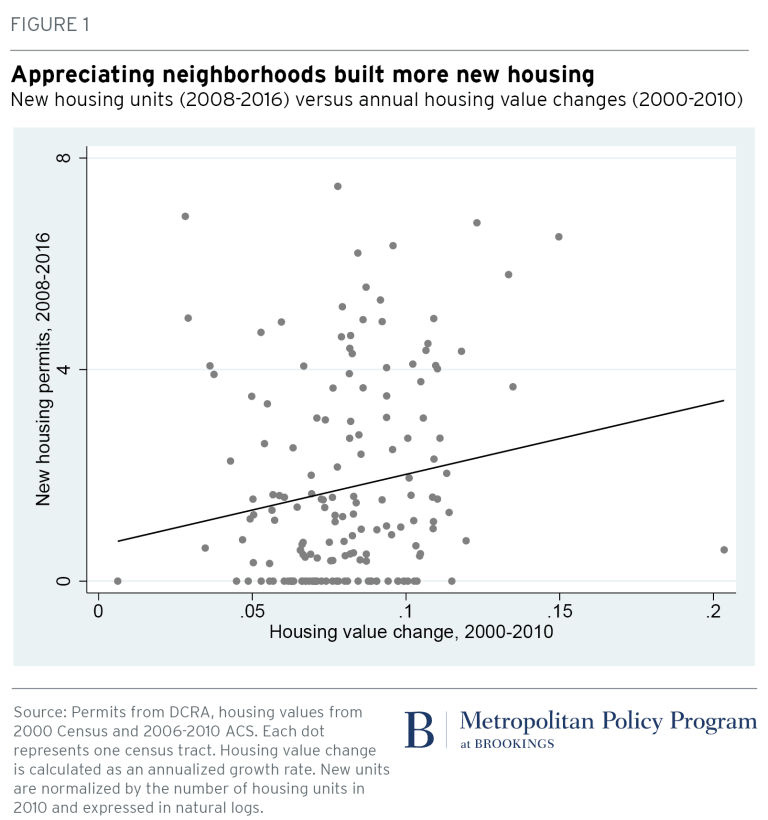

That’s when people are relatively free to bring in more stock. But Brookings also found that restrictive zoning prevented new supplies and had another effect that made housing prices even more expensive:

Restrictive zoning makes affordability worse in two ways. Not only does it limit the amount of new construction, but it also encourages property owners in expensive neighborhoods to upgrade the size or quality of existing structures, thereby making them still more pricey. For instance, many single-family homes or rowhouses in high-value neighborhoods expand the size of the house by adding another story on top, or “bumping out” the rear exterior walls (Figure 4). These expansions or interior upgrades such as kitchen and bathroom renovations increase the value of the home but do not expand the number of homes in a neighborhood. Additions and alterations benefit existing homeowners, but make it more difficult for new residents to buy into those neighborhoods.

Note: the Brookings paper focused on new single-family homes and large apartment buildings and didn’t include ADUs. But a greater range of options would naturally include a greater range of prices.

Planners, policymakers, and other concerned citizens want more affordable housing options and less traffic congestion. But instead of more regulation, the way to bring those things about more effectively may be less restrictive land-use and other regulations. With fewer government obstacles and more freedom to operate, people can respond to market needs more quickly and in a greater variety of ways.