- NC State researchers in 2016 found that 80 percent of North Carolina beachgoers would either not return to a beach rental if wind turbines were visible — or require an unreasonable discount for spoiled views

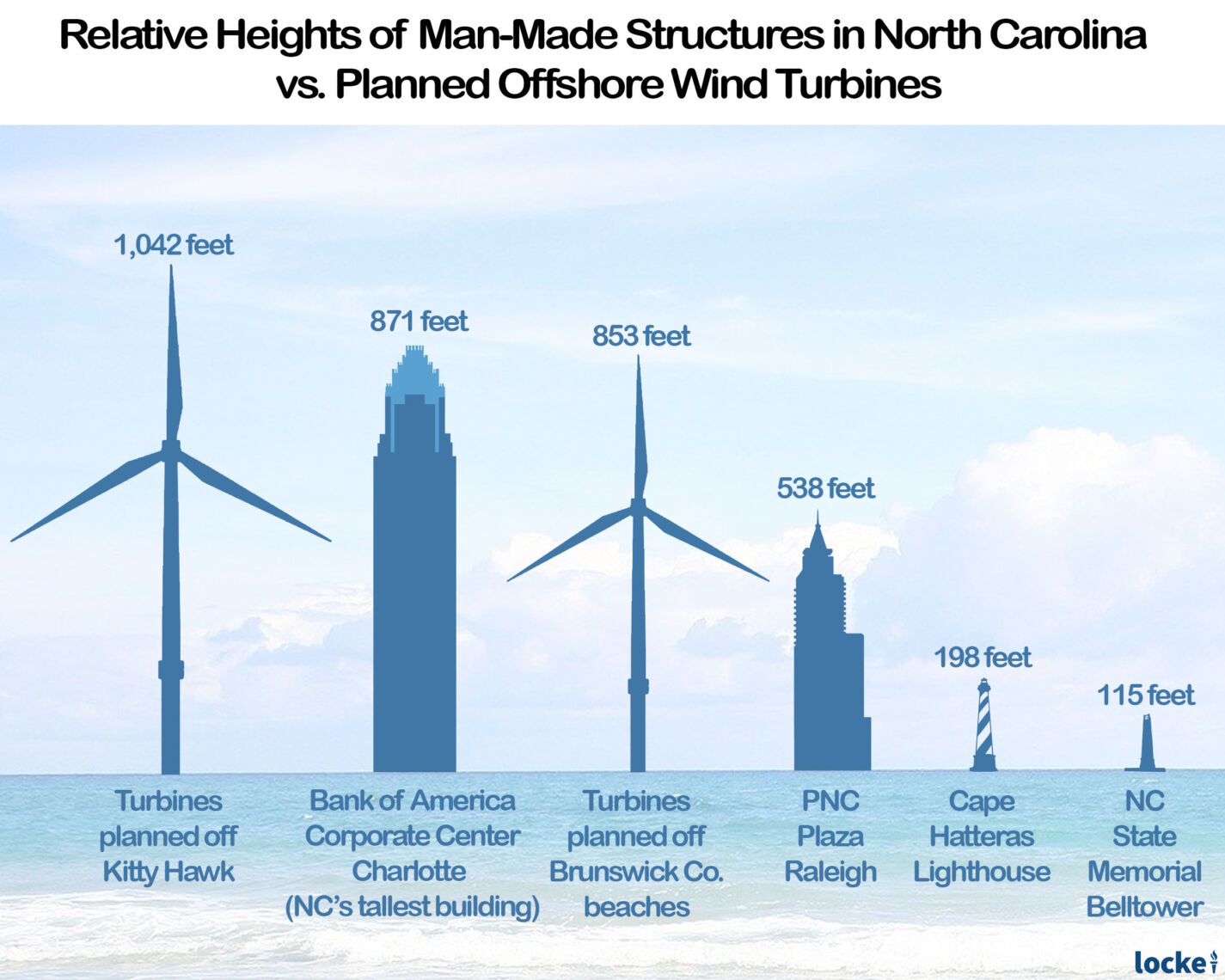

- That study asked respondents about wind turbines that were over 500 feet tall, much smaller than the ones being planned off Brunswick County beaches (853 feet tall) or for the Kitty Hawk wind energy area (1,042 feet tall)

- The General Assembly passed the Mountain Ridge Protection Act of 1983 to prevent mountaintop condominiums and hotels spoiling the viewsheds in tourism-dependent North Carolina mountain communities

The previous research briefs have discussed the research and physics underlying why large arrays of enormous wind turbines with flashing lights would be major features on the coastal horizons of North Carolina. This brief will discuss why negative tourism effects are to be expected from offshore wind turbine arrays and look at how state leaders responded to a prior threat to destroy the scenic beauty of another part of the state heavily dependent on tourism.

NC State survey: 80 percent of North Carolina beach home renters would not rent again

In 2016 the Center for Environmental and Resource Economic Policy of North Carolina State University conducted a survey of beach tourists with respect to offshore wind turbines on the coastal horizon. This survey found that North Carolina beach tourists are highly sensitive to viewshed disruption by wind turbines.

The 484 survey participants had all recently rented beach vacation homes in North Carolina in areas under consideration for offshore wind energy development. An NC State News release describes the survey design:

In the survey, study participants were asked to consider renting the same vacation house they had just rented, but with one change: the view would include wind turbines off the coast.

Participants were shown various sets of photographs. Two control photographs were of a view from the beach looking over the ocean – one taken at night, one during the day. The same photos were then altered to include up to 144 wind turbines at 5, 8, 12 or 18 miles offshore. Some participants were told they would get a discount on their rental price if wind turbines were present; some were told they would pay more; and some were told there would be no change in rental cost. Discounts went as high as 25 percent off the original rental price.

To reiterate, recent beach tourists were asked if they would rent the same beach house they had just rented — even at discounted rates — if their beach views would now include an array of 144 wind turbines at varying distances from shore: five, eight, 12, or 18 miles.

The majority — 54 percent — of recent North Carolina beach home renters said they would not rent a beach home, not even with a large discount, “if turbines were in view at all.”

The turbines in the study design were over 500 feet tall — much smaller than turbines now being considered. Turbine heights being planned off the coast of Bald Head Island and other Brunswick County beaches would reach 853 feet tall, a few feet short of the tallest building in North Carolina (Charlotte’s 871-foot-tall Bank of America Corporate Center). Turbines for the Kitty Hawk wind energy area would be significantly taller than those: 1,042 feet tall.

The study found that a majority — 54 percent — “said they would not rent a vacation home if turbines were in view at all, no matter how large a discount was offered on the rental price.” So over half the survey participants said even a large discount wouldn’t be enough, that they refuse to return to their previous beach house rental “if turbines were in view at all.” The finding suggests that tourism at affected beaches would take an enormous hit, not just for one season but ongoing.

Another 26 percent wanted discounts if the turbines were 12 miles offshore — but “the discounts they needed if turbines were closer than 12 miles were so high as to be completely unrealistic.” So 80 percent of North Carolina beachgoers would not return to a beach rental if wind turbines were visible — most because they’d refuse to have their views spoiled, and the rest because they’d demand too much of a discount for spoiled views.

The 20 percent remaining had a greater tolerance for visible wind turbines. They were willing to accept a slight discount averaging about 5 percent, and only if turbines were closer in — eight miles offshore.

Again, respondents were presented views of offshore turbines over 500 feet tall, not 853 feet tall (70 percent taller). The Wilmington West wind energy area off the coast of Brunswick County beaches would start around nine nautical miles (10.4 miles). So regardless of the much taller turbine heights, it would be within 12 miles from shore.

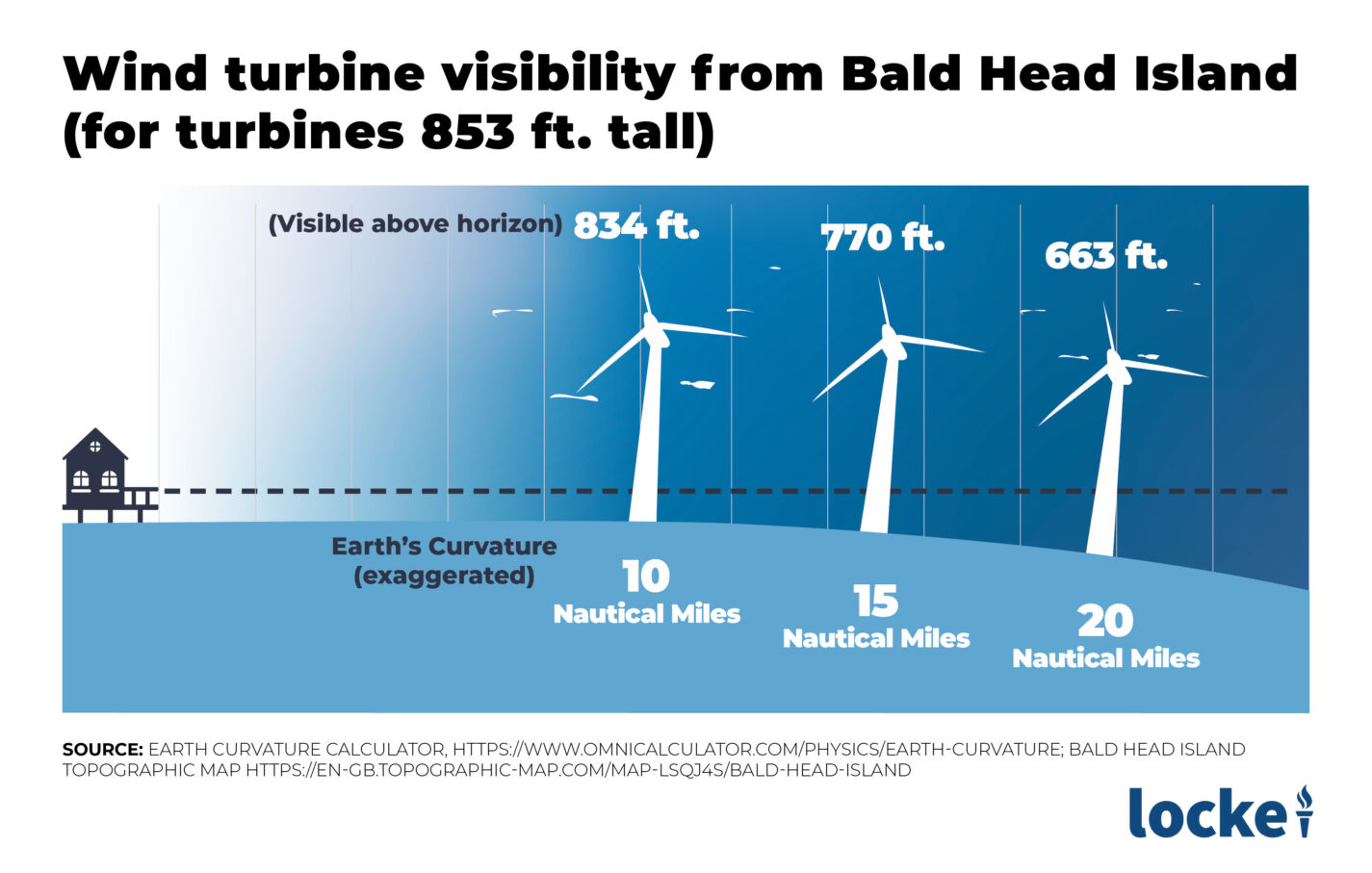

The Wilmington East wind energy area off Bald Head Island would start around 15 nautical miles (17.3 miles), but as discussed in the previous research brief, a person overlooking the ocean from a beach house on stilts would be able to view the upper 770 feet of the taller turbines.

Coastal residents have every reason to expect not only significant viewshed disruption, but also significant economic disruption from offshore wind turbine arrays.

The Ridge Law: When lawmakers acted to protect scenic views and tourism

The mountains of North Carolina also feature destinations that residents, vacationers, and tourists seek out for breathtaking views and contemplative beauty. When a ten-story condominium was placed atop Little Sugar Mountain in 1982-83, not only spoiling the viewshed in the surrounding areas but also threatening a near future of construction dotting the surrounding mountaintops, the General Assembly responded quickly with the Mountain Ridge Protection Act of 1983 (Ridge Law) to prevent further ridgeline disfigurement.

The Ridge Law was “the first state-level imposition of land-use restrictions for primarily aesthetic purposes,” noted Robert M. Kessler in the North Carolina Law Review. Prior to the Ridge Law, such restrictions were made by local governments (e.g., creating historic preservation districts). Nevertheless, “the Act’s primary concern is preserving the scenic beauty of the mountains,” Kessler wrote, as the public’s “main concern was spoliation of mountain scenery.”

Concerns about the destruction of scenic views and natural beauty won out even despite there being an argument that mountaintop condominiums and hotels could help, not harm, tourism and therefore the local economies — by bringing in more people. No such argument could be made credibly for enormously expensive arrays of offshore wind turbines, however.

Studies estimate that meeting Gov. Roy Cooper’s goal of 8 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind production would cost $55.7 billion to $71.5 billion, greatly raising electricity rates and leading to an estimated loss of 45,000 to 67,000 permanent jobs (and that’s not counting tourism impacts). Even the North Carolina Utilities Commission’s initial Carbon Plan acknowledged there would be higher rates from taking on more wind and solar energy — and that they would mean fewer jobs.

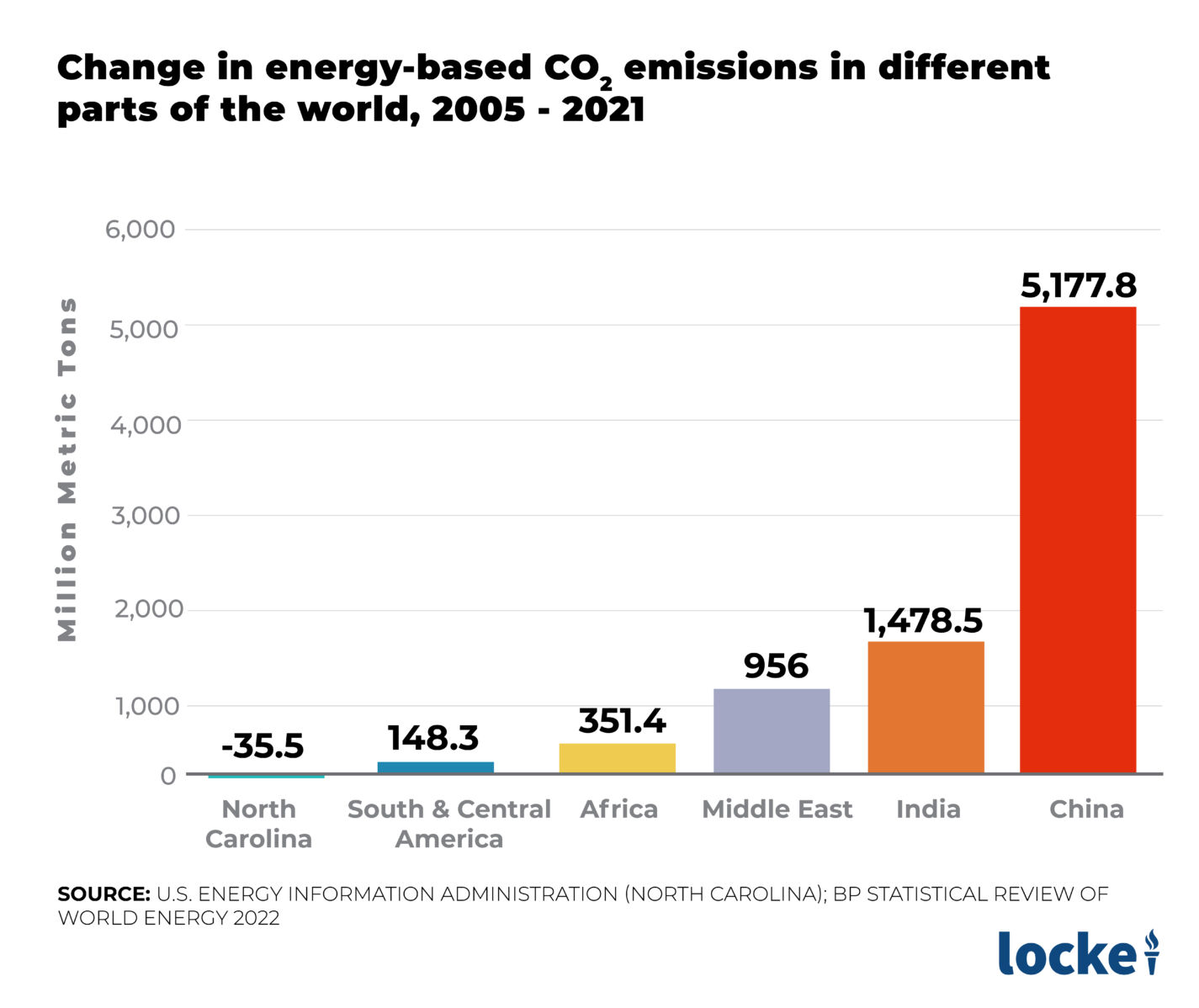

The real kicker: forcing these great costs on North Carolinians in general and our coastal communities in particular thinking it’s “worth it” to reduce global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions is just plain wrong. Even as North Carolina’s CO2 emissions have been cut nearly in half without building expensive offshore wind facilities, the rest of the world keeps adding to CO2 emissions in such large amounts as to negate and overwhelm North Carolina’s reductions — even if we completely eliminated all of our CO2 emissions.

Forcing offshore wind development in North Carolina can’t do anything for the world’s climate, but it would make affected coastal communities poorer — and leave North Carolinians worse off with more expensive, less reliable electricity.