Known primarily for his statement that “the chief business of the American people is business,” and for saying little else, Calvin “Silent Cal” Coolidge has escaped much of the scrutiny that many of his presidential predecessors and successors have enjoyed.

Known primarily for his statement that “the chief business of the American people is business,” and for saying little else, Calvin “Silent Cal” Coolidge has escaped much of the scrutiny that many of his presidential predecessors and successors have enjoyed.

But that situation is changing. Regular readers in this forum have encountered numerous references to The High Tide of American Conservatism, Garland Tucker’s book about the 1924 election pitting the Republican Coolidge against Democrat John W. Davis.

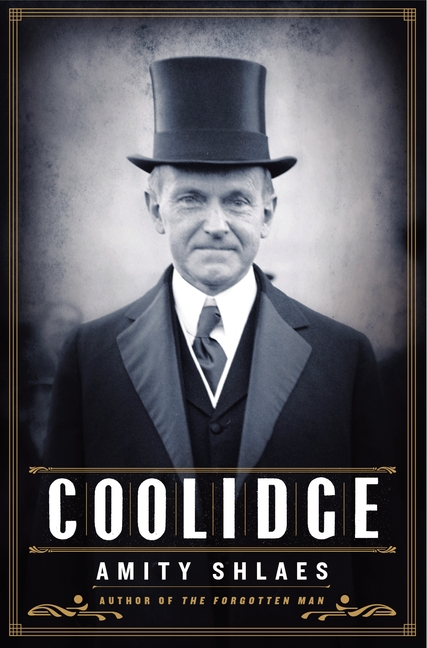

Amity Shlaes also has devoted a full biography to Coolidge. Among the more interesting facts this reader learned from Shlaes’ Coolidge is that — like Ronald Reagan, who admired Coolidge — the 30th president was a convert to conservative political thought. Sure, he was personally conservative from his earliest days in rural Vermont. But Coolidge — unlike Reagan — was a lifelong Republican, and that meant support during his early adult years for the Progressive policies of Theodore Roosevelt.

By the time he had served in the Massachusetts legislature and as lieutenant governor and governor of that state, though, Coolidge had seen greater value in policies that placed more faith in people than in government. The results, Shlaes recounts, were remarkable.

Coolidge served for sixty-seven months, finishing out [Warren] Harding’s term after Harding died in early August 1923 and remaining until early March 1929. Under Coolidge, the federal debt fell. Under Coolidge, the top income tax rate came down by half, to 25 percent. Under Coolidge, the federal budget was always in surplus. Under Coolidge, unemployment was 5 percent or even 3 percent. Under Coolidge, Americans wired their homes for electricity and bought their first cars or household appliances on credit. Under Coolidge, the economy grew strongly, even as the federal government shrank. Under Coolidge, the rates of patent applications and patents granted increased dramatically. Under Coolidge, there came no federal antilynching law, but lynchings themselves became less frequent and Ku Klux Klan membership dropped by millions. Under Coolidge, a man from a town without a railroad station, Americans moved from the road into the air.

Under Coolidge, religious faith found its modern context: the first great White House Christmas tree was lit, an ingenious use for the new technology, electricity. Under Coolidge, the number of local telephone calls went up by a quarter. In Silent Cal’s time, Americans learned to chatter. Under Coolidge, wages rose and interest rates came down so that the poor might borrow more easily. Under Coolidge, the rich came to pay a greater share of the income tax.

Shlaes offers plenty of praise, but this is no hagiography. Readers are likely to find cases in which they disagree with Coolidge’s choices, both personally and politically. And those who read the book between now and Sept. 23 will have a chance to ask Shlaes about it. She speaks in Raleigh that day for the John Locke Foundation.