- Crime rates soared between 1960 and 1980 and remained high throughout the rest of the century, making fighting crime and restoring order national priorities

- The burden of crime and disorder fell most heavily on Black Americans and the poor, who were far more likely to be crime victims than other demographic groups

- The crime wave accelerated the flight of middle-class white people and successful businesses to the suburbs and left the remaining residents trapped in a cycle of poverty that continues to this day

In terms of crime and public order, the middle decades of the 20th century were a period of remarkable tranquility. In the decades that followed, however, crime rates soared. Between 1960 and 1980, the victimization rate for homicides more than doubled.

The rate for other violent crimes rose even faster, from 161 victimizations per 100,000 people in 1960 to the staggering level of 741 victimizations per 100,000 people in 1990.

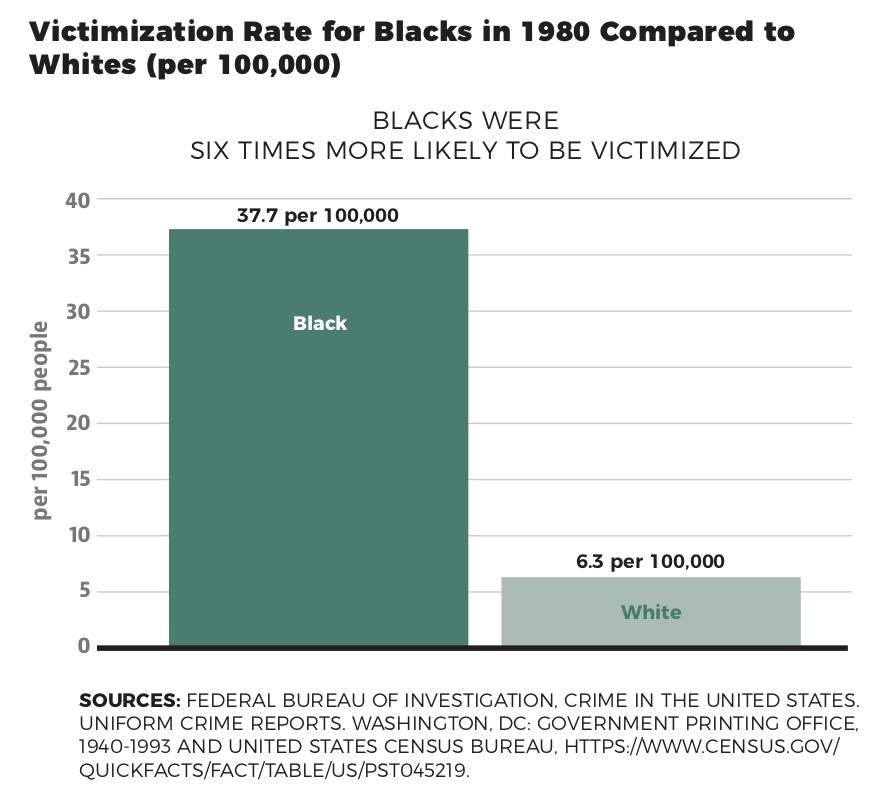

The burden of that additional crime fell especially heavily on Blacks and the poor. For example, of the 23,040 Americans murdered in 1980 when the homicide victimization rate reached its peak, 9,767 were Blacks. Given their relative numbers within the population at the time, that means that the victimization rate for Blacks in 1980 was six times as high as it was for white Americans.

For the victims themselves, and for their families, the direct costs of the crime wave were considerable and included not just whatever monetary value might be assigned to all the additional lost lives and property, but incalculable amounts of pain and suffering as well. Substantial though they were, however, the direct costs of the crime wave were only part of the story. The crime wave imposed indirect costs on all the residents of high-crime communities, and the breakdown in public order that went hand in hand with the rise in crime imposed indirect costs as well. As with the direct costs, the burden of all of these indirect costs fell most heavily on Blacks and the poor.

One major indirect cost of the rise in crime and disorder was the climate of fear that degraded the quality of life for the residents of high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods. In his best-selling memoir, Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates described a childhood blighted by that kind of constant fear:

[T]he only people I knew were black, and all of them were powerfully, adamantly, and dangerously afraid. I had seen this fear all my young life. … It was always right in front of me.

I felt myself to be drowning in the news reports of murder. I was aware that these murders very often did not land upon the intended targets but fell upon great-aunts, PTA mothers, overtime uncles, and joyful children—fell upon them random and relentless, like great sheets of rain.

The crews, the young men who’d transmuted their fear into rage, were the greatest danger. … They would break your jaw, stomp your face, and shoot you down.

[E]ach day, fully one third of my brain was concerned with who I was walking to school with, our precise number, the manner of our walk, the number of times I smiled, who or what I smiled at, who offered a pound and who did not. … I think somehow I knew that that third of my brain should have been concerned with more beautiful things. I think I felt that something out there, some force, nameless and vast, had robbed me.

Maintaining a constant state of vigilance, as Coates did as a boy, is one way of dealing with the presence of dangerous and disorderly people. Avoiding contact with such people by staying indoors is another option, one that is often chosen by older people. Both options impose costs on those who choose them. Coates was quite justified in feeling he had been robbed. He had been robbed, not just of his time and mental effort, but of the joy of childhood. Living in constant fear unquestionably does psychological harm to the residents of high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods, and there is at least some evidence that it does physical harm as well.

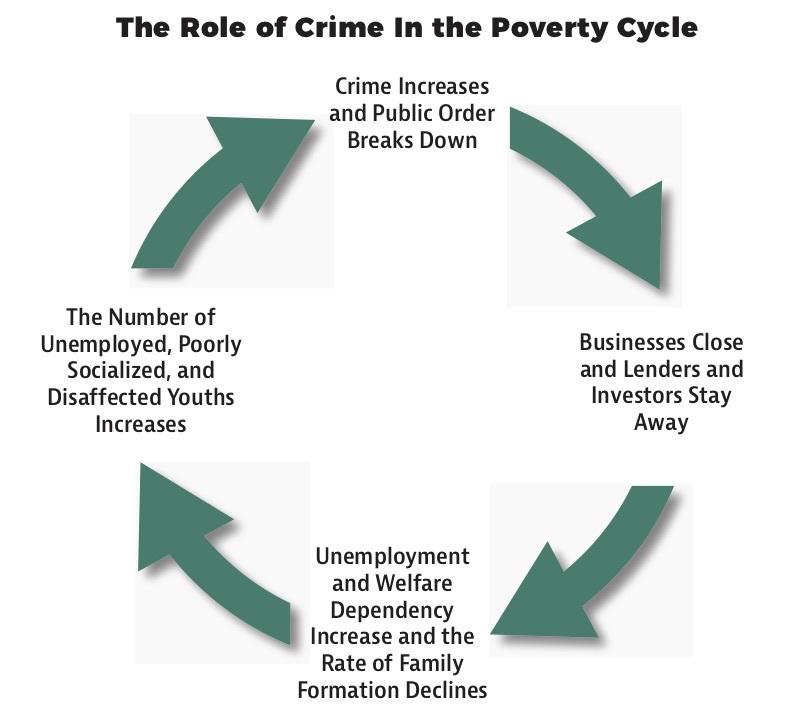

Heightened vigilance and staying indoors are not the only ways of dealing with crime and disorder. If one can afford to do it, one can simply move away — or stay away — from the neighborhoods in which the levels of crime and disorder are high. As the crime wave gathered momentum in the early 1960s, and throughout the remainder of the 20th century, more and more middle-class individuals and families moved from high-crime inner-city neighborhoods to safer and more tranquil suburbs. Many businesses left as well. And because lenders and investors also steered clear of dangerous and disorderly neighborhoods, new families and new businesses failed to take the places of those who left.

The result was fewer jobs and higher rates of unemployment in high-crime neighborhoods. The high rate of unemployment, in turn, meant that fewer young people married and formed families and that more children were born into and grew up in single-parent, welfare-dependent households. Completing the pernicious cycle, the lack of jobs and the prevalence of single-parent households made crime and disorder even more prevalent, which drove even more people and businesses away. For the predominantly poor and Black residents who remained, the indirect costs of crime — the fear, the unemployment, the inability to form families, and the generally degraded quality of life — were higher than ever.

Note: This brief is an amended excerpt from a longer policy report called “Keeping the Peace: How Intensive Community Policing Can Save Black Lives and Help Break the Cycle of Poverty.” Additional excerpts will be posted in the coming weeks. In one of those excerpts I point out that unless we take steps quickly to bring it under control, the new crime wave that began in the spring of 2020 will also be a disaster for Blacks and the poor. In another I advocate a specific approach to doing that, namely, “the strategic deployment of large numbers of well-trained and well-managed police officers in high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods.”

For additional information see: