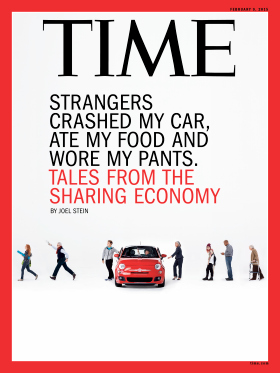

N.C. lawmakers looking into potential regulation of the “sharing economy” might be interested in TIME magazine’s latest cover story: humorist Joel Stein‘s description of his own experience with the new technology-based businesses.

N.C. lawmakers looking into potential regulation of the “sharing economy” might be interested in TIME magazine’s latest cover story: humorist Joel Stein‘s description of his own experience with the new technology-based businesses.

The key to this shift was the discovery that while we totally distrust strangers, we totally trust people–significantly more than we trust corporations or governments. Many sharing-company founders have one thing in common: they worked at eBay and, in bits and pieces, re-created that company’s trust and safety division. Rather than rely on insurance and background checks, its innovation was getting both the provider and the user to rate each other, usually with one to five stars. That eliminates the few bad actors who made everyone too nervous to deal with strangers. “They figured out a way to move from a no model to a yes model,” says Nick Grossman, a general manager at Union Square Ventures, a venture-capital firm that invests heavily in sharing-economy companies. “The traditional way is you can’t do it unless you get a license. That made sense up until we had data. Now the starting point is yes.”

It’s unclear if most of this is legal. The disrupters are being taken on by governments and the entrenched institutions they are challenging. Uber and Airbnb, exorbitantly funded by Silicon Valley, generate most of the controversy. But there are thousands of companies–in areas such as food, education and finance–that promise to turn nearly every aspect of our lives into contested ground, poking holes in the social contract if need be. After transforming or destroying publishing, television and music, technology has come after the service economy. …

… The convenience and low price of Lyft and Uber rides are destroying cab monopolies around the world. But it doesn’t hurt that amateur drivers are surprisingly pleasant. No matter how well trained service employees might be, everyone is nicer when they’re dealing with customers directly. Even customers. Nearly everyone who stays at an Airbnb rental, for instance, hangs up their bathroom towels after they use them. You do not want to ask a hotel manager what guests do with their towels. I would still have cable television if I could have bought it from a dude who owned it instead of being transferred by 12 different Time Warner Cable representatives when I tried to alter my service–and then having the company call my cell phone several days later, somehow pre-emptively putting me on hold when I picked up. …

… [W]e’ve built up a lot of regulations. In the 1950s, 5% of jobs required a license; now it’s one-third. “One hundred years ago there wasn’t a clear line between someone who ran a hotel and someone who let people stay in their homes. It was much more fluid,” says Arun Sundararajan, a professor at New York University Stern School of Business who studies the sharing economy. “Then we drew clear lines between people who did something for a living and people who did it casually not for money. Airbnb and Lyft are blurring these lines.”