- A recent report placed North Carolina second in the nation for threatened farmland from residential development

- Meanwhile, the amount of new solar facilities sought by Duke Energy could endanger as much farmland as has been preserved by the state’s Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Trust Fund

- A law requiring that any retiring source of baseload power generation be replaced with an equal or greater amount of new baseload generation would help preserve our farmland and reliable electricity generation

Disappearing farmland in North Carolina is a big concern for this fast-growing state. About one-fifth of the state’s workforce is employed in agriculture, which is the state’s top industry. A recent report from the American Farmland Trust (AFT) ranked North Carolina second in the nation for threatened farmland from residential development.

Loss of farmland threatens a key economic driver and job provider in North Carolina. Residential development is not the only threat to farmland, however.

Farmland endangered by residential development — and solar facilities

North Carolina Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler recently said North Carolina has about 8.3 million acres of farmland. AFT estimated that the state could lose a sizeable chunk — 1.2 million acres of farmland — to residential development by 2040, possibly even more. Troxler cited the state’s Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Trust Fund for preserving 34,000 acres of working farmland.

Another threat is the possibly accelerated loss of farmland to solar facilities. Troxler told Carolina Journal that the state had already lost 40,000 to 45,000 acres of farmland to solar facilities.

The initial Carbon Plan handed down by the North Carolina Utilities Commission (NCUC) on the final day of 2022, called for Duke Energy Carolinas and Duke Energy Progress (Duke) to procure 2,350 megawatts (MWs) of new solar generation to be placed into service by 2028. It’s a huge amount — two and a half times greater than the largest amount of solar Duke had ever interconnected in a single year. That directive also came one month after the NCUC had ordered Duke to procure 1,200 MWs of new solar generation.

North Carolina’s endangered farmland would have to site all of that new solar, too.

Solar’s ravenous appetite for farmland

It’s well-known solar has a voracious appetite for land. The John Locke Foundation’s Policy Solutions estimated that a 1,000-MW solar facility in North Carolina needs over 13.2 square miles — or about 8,500 acres. By comparison, zero-emissions nuclear needs only one square mile, and natural gas needs just 1.7 square miles, to produce the same amount of energy.

Duke’s new solar procurements listed above, however, would total 3,550 MWs. They could potentially threaten as much farmland as has been preserved by the trust.

Going further, by 2038 Duke’s proposed updated integrated resource plan for the Carolinas would add 17,500 MWs of new solar. If that were to happen, it would eliminate around 150,000 acres of farmland.

All that lost farmland for intermittent, unreliable power?

Solar facilities’ enormous land footprints mean they need to be built away from population centers and therefore need new transmission lines built.

Intermittency is a major problem. The coal plants Duke is directed to close are all baseload power sources. That means they, like nuclear, are the workhorse power plants, the ones supporting the state’s known underlying demand for electricity at any point in time. Additional variations of demand above the baseload level can be covered by dispatchable sources, natural gas and hydroelectric. Dispatchable is the opposite of intermittent; a dispatchable source can be ramped up and down quickly in response to fluctuations in electricity demand.

“Solar is an intermittent energy source, and therefore the maximum dependable capacity is 0 MW.”

Strata Solar’s application to build a solar farm on Gov. Roy Cooper’s Nash County property

What solar (and wind power) can offer is intermittent or unreliable power. Solar and wind can never be relied upon as baseload sources. Nor can they be relied upon as dispatchable sources. They produce what they can when they can, based on weather conditions and time of day. As Strata Solar disclosed in its application to build a solar farm on Gov. Roy Cooper’s Nash County property: “Solar is an intermittent energy source, and therefore the maximum dependable capacity is 0 MW.”

For example, Monday, Feb. 12, was overcast and rainy. Here is how the weather map looked that day (screenshot from WRAL’s map):

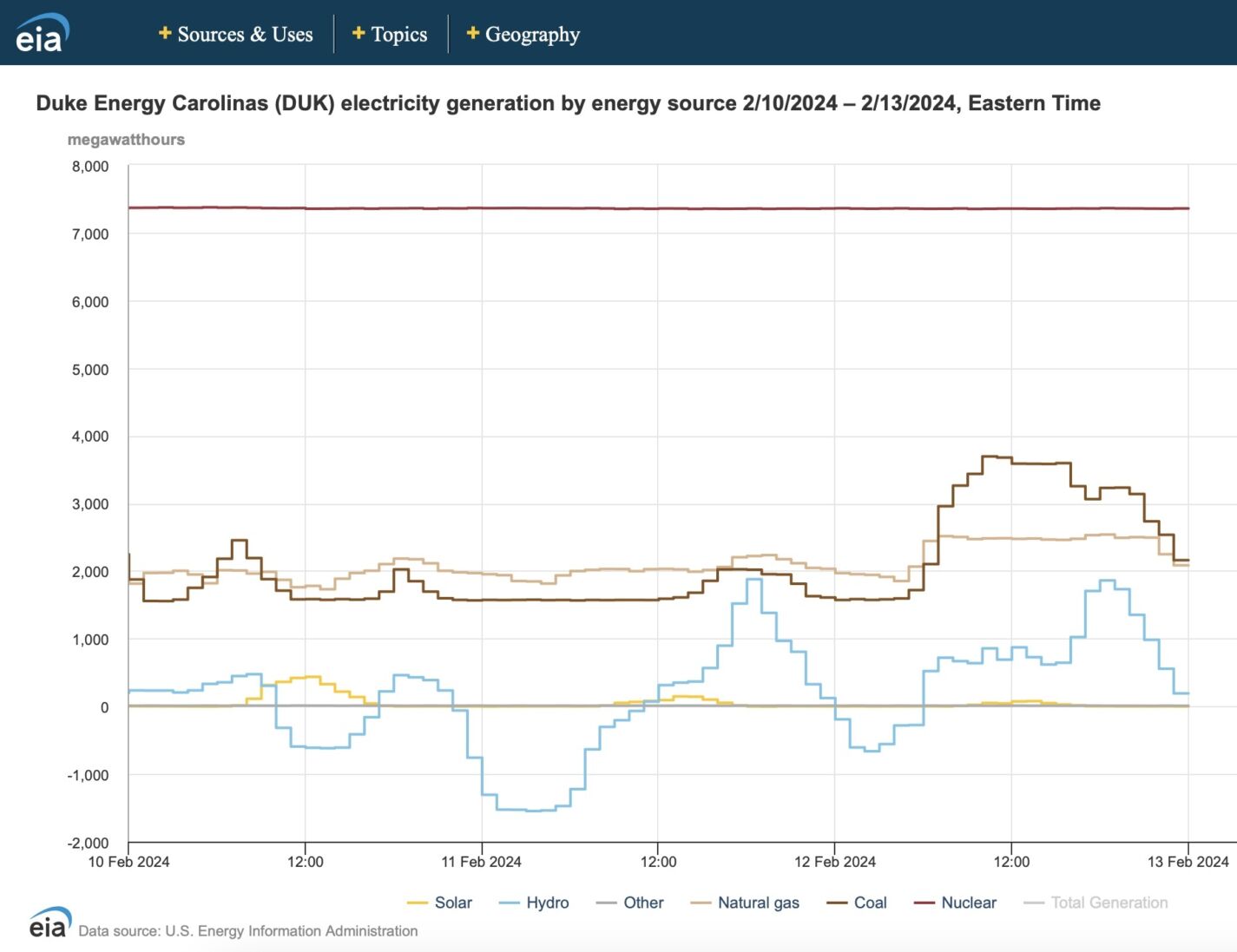

Here is the hourly production of electricity from Duke Energy Carolinas that day, according to the U.S. Electricity Information Administration’s grid monitoring site. There was hardly any solar production at all (nor was there much the previous day, which was overcast).

That’s zero-emissions nuclear (baseload) at the very top.

With solar being so intermittent while also being pushed so hard politically with subsidies, laws, and regulations, utilities have to overbuild solar facilities just to approximate the productivity expected from dispatchable facility of the same size. A recent brief on reliable power generation discussed this problem. Utilities use a metric called effective load carrying capacity (ELCC) to measure how much additional new electricity demand could be met by adding a renewable resource to the system. ELCC is basically a measure to excuse overbuilding. If the ELCC of a renewable resource is 40 percent, it means it would take building 100 MWs of the resource to balance only 40 MWs of new demand.

In 2022 Duke commissioned a study of the ELCC of new solar resources, which showed how solar’s variable productivity also varied according to time of year and capacity. Solar ELCC for Duke Energy Carolinas ranged from averaging 45.4 percent during the summer down to averaging only 3.5 percent in the winter.

If politics forbids working solutions, then the only way to get close to 100 percent for something that unreliable is to throw a lot of redundancy into the system. That is, overbuild. Charge ratepayers to construct eight facilities in the hopes of getting the stated capacity of one.

Overbuilding also requires lots more transmission infrastructure. Duke rates are already increasing, and Duke officials explained it is mostly because of grid infrastructure improvements and new solar facilities (they opted for the “transitioning to clean energy” euphemism). The NCUC’s Public Staff has publicly warned that electricity rates could be “approximately double” by the end of the decade.

Ways forward

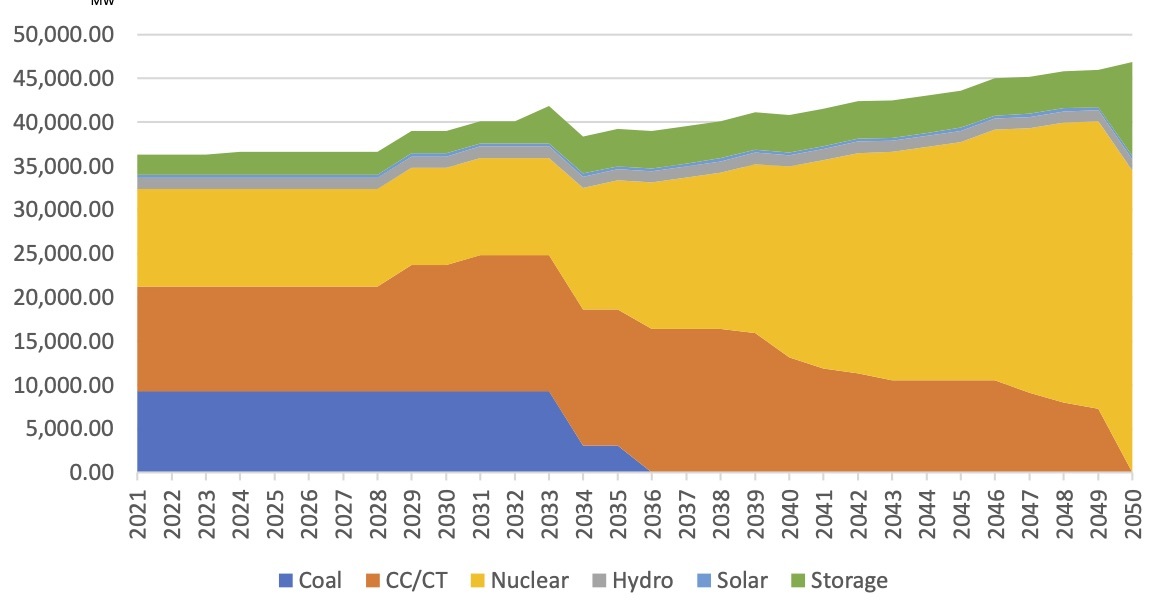

For these reasons Locke’s Center for Food, Power, and Life modeled to the NCUC how to achieve the Carbon Plan’s goals with less cost and more reliability: add more zero-emissions nuclear power, pumped storage, battery storage, and natural gas facilities, not overbuild solar and wind.

Model Least-Cost Decarbonization Portfolio: Nuclear, Pumped Storage, Battery Storage, and Natural Gas

It is also why Locke’s top recommendation for electricity policy is to pass a law that would:

Require that any retiring source of baseload power generation be replaced with an equal or greater amount of new baseload generation, commensurate with increased electricity demand.

These solutions would also help preserve North Carolina’s vital but dwindling farmland in the coming years. Overbuilding unreliable solar facilities to try to replace baseload coal plants would lead not only to uncertain power with higher power bills, but also more expensive food and fewer agriculture jobs.

Note: This article has been changed to remove an error in the calculations.