- Minimizing the number of split counties limits gerrymandering

- The court-imposed Stephenson process restricts the number of county splits

- The Stephenson process should be added to the North Carolina Constitution

The North Carolina State Constitution already requires the General Assembly to have as few county splits as possible when drawing state legislative districts. It is time to add the process used to achieve that goal into the constitution.

Keeping Counties Whole Combats Gerrymandering

I wrote on April 9 about why those drawing maps should avoid splitting counties when drawing districts. Keeping county splits to a minimum keeps one of the most essential political communities of interest whole:

Political boundaries often have meaning for the people who live in them. People have political, legal, and emotional attachments to counties and municipalities.

Municipalities and especially counties should be split as little as possible between districts. Likewise, large enough political communities should contain a whole district.

The John Locke Foundation noted in our 2023 research report, “Limiting Gerrymandering in North Carolina,” that a redistricting requirement for keeping counties united whenever possible “severely limited (but did not make impossible) the ability of state legislators to draw egregious districts.”

In other words, minimizing county splits restricts gerrymandering no matter who draws the districts.

The state constitution also requires it. The North Carolina Constitution (Article II, Sections 3 and 5) has four requirements for drawing state legislative districts:

- They must be contiguous.

- They must, “as nearly as may be,” have equal populations.

- No county can be divided when making districts.

- They cannot be drawn again for a decade (except under court order).

The General Assembly partially tried to follow those requirements by using multimember districts. For example, the North Carolina House split its 120 members among 98 districts in the 1990s, including five three-member districts and twelve two-member districts.

The Stephenson Process: North Carolina’s Unique Anti-Gerrymandering System

The North Carolina Supreme Court’s ruling in Stephenson v. Bartlett functionally banned multimember districts.

The ruling also stopped another pernicious practice: ignoring the constitutional requirement against dividing counties. While it is impossible to completely follow that requirement and the equal population requirement simultaneously, the legislature violated the former well beyond what is required to follow the latter.

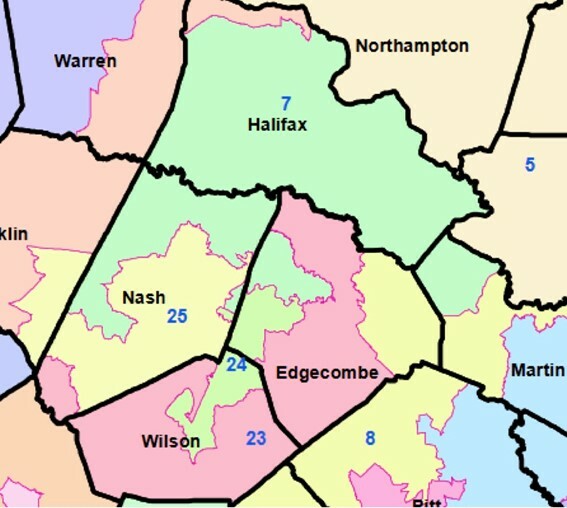

That practice resulted in maps with egregious county splits in the service of gerrymandering. An example of the problem is seen in Figure 1, a detail of the North Carolina House map passed in 2001.

Figure 1: Detail of Sutton House Plan 3, passed by the General Assembly in 2001

Source: North Carolina General Assembly

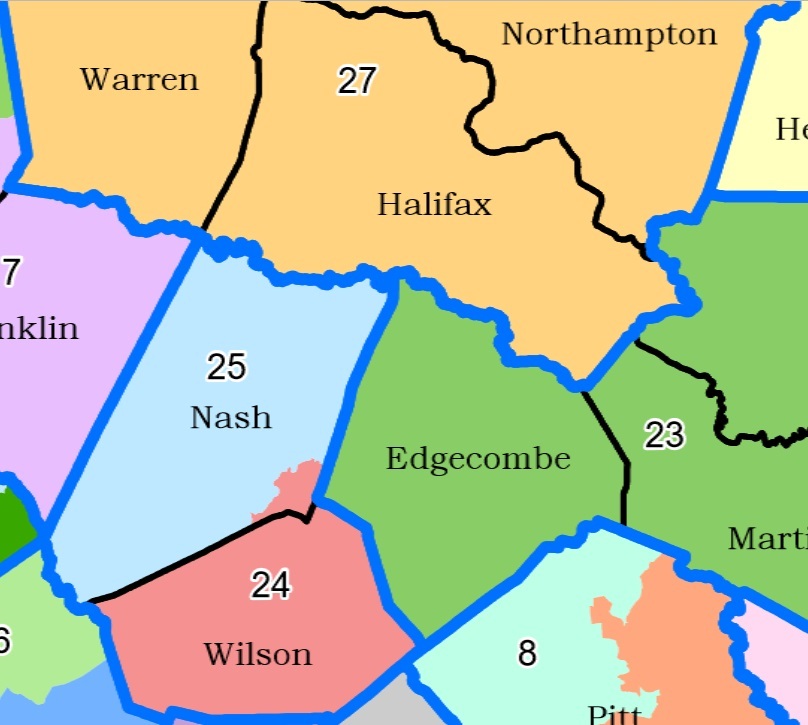

The court banned those extreme county divisions by requiring legislators to group counties by population before drawing districts within them and by requiring districts to traverse county lines the minimum number of times necessary to maintain an equal population (within five percent). As demonstrated in Figure 2, there are far fewer county divisions today, helping keep communities of interest together.

Figure 2: Detail of map drawn under House Bill 898, passed by the General Assembly in 2003

The blue lines are county grouping boundaries, and the black lines are county boundaries within county groupings.

Source: North Carolina General Assembly

While not an explicit goal of the court, the Stephenson process is an effective tool against gerrymandering because it limits legislators’ creativity when drawing maps. It is no accident that the Republican-controlled General Assembly drew a much smaller proportion of state legislative seats that favored their party (less than 60 percent) compared to congressional seats (over 70 percent). As one mapping expert noted, “Does the Stephenson process constrain mapmakers’ ability to create misshapen districts? Absolutely.”

It Is Time to Formalize the Stephenson Process in the State Constitution

While the Stephenson decision helped limit gerrymandering, it was also a case of aggressive judicial activism in which the court “seized the opportunity to impose a long list of new districting criteria on the General Assembly.” Rather than telling the General Assembly the constitutional limits they must follow when drawing state legislative districts, the court told them how to draw those districts, something the constitution reserves to the legislative branch.

Justice Bob Orr pointed out the problem in his partial dissent in Stephenson (pages 62-63):

[T]he context of legislative redistricting — which is a duty specifically assigned to the General Assembly under our State Constitution — requires a reviewing court to impose remedial actions as narrowly as possible. … This Court should not attempt to micromanage the legislative function of drawing new districts.

The General Assembly has followed the Stephenson process since the 2001 ruling. However, as progressives discovered in a redistricting ruling last year, what the court gives without a solid foundation in the state constitution, the court can take away.

So, what are we to do about a court-imposed process that helped the General Assembly better follow the North Carolina Constitution but is itself a constitutional overreach?

One answer is to put the process itself into the constitution.

That was part of the FAIR Act (House Bill 140, introduced in the 2019 session but not passed), a bipartisan bill that would have included other redistricting reforms, such as a ban on using partisan or racial data to draw districts, no consideration of incumbent address, and the creation of a bipartisan advisory redistricting commission. The section spelling out the Stephenson process is on page two, lines 32–42 of HB 140.

Redistricting Reform Should Not Wait Until 2031

The best time to implement redistricting reform is well before the next scheduled round of redistricting in 2031, when short-term political calculations would make passing reforms more difficult.

The General Assembly should reconsider the FAIR Act and give voters a chance to formalize the Stephenson process in the North Carolina Constitution when they vote in the November general election.To learn more about the Stephen process, you can read this explainer from Locke and a more detailed explanation using older data.