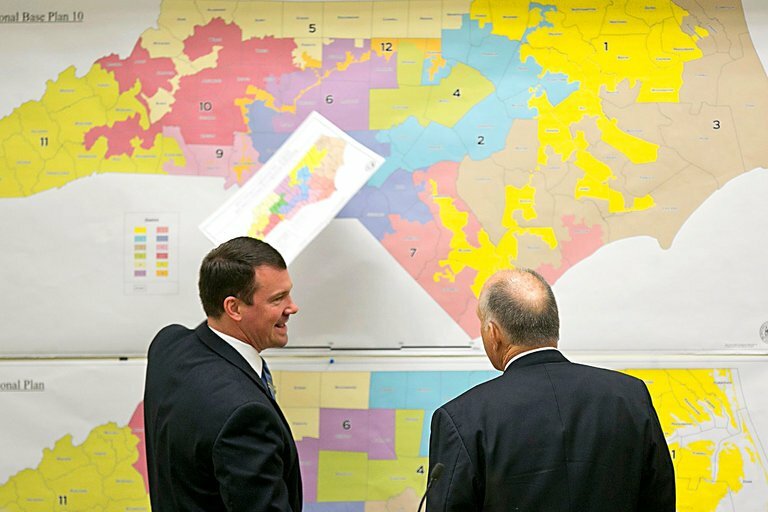

It has been several decades since North Carolina produced a set of congressional and state legislative redistricting maps that have survived for an entire decade. Courts have struck down many of those maps for racial and, more recently, political gerrymandering. Even those maps that survive litigation are widely seen as unduly benefiting the majority party in the North Carolina General Assembly.

Traditional redistricting criteria can be more strictly applied to limit the ability of those drawing legislative districts to benefit one political party. Those criteria include the following:

- Maintain current criteria from the North Carolina State Constitution. Those include equal population (with a small permitted variance for state legislative districts and an even smaller allowed variance for congressional districts), contiguity, and minimizing county traversals.

- Do not use partisan data, such as voter registration and election results. Racial data is not necessary for compliance with the Voting Rights Act and should not be used, because there is some correlation between racial and partisan data. Do not consider incumbents’ addresses when drawing districts to avoid “double-bunking.”

- When drawing maps, do not consider statewide measures, such as particular partisan balances or making more districts that are competitive. Instead, focus on measures that help solidify districts’ relationships with their local communities. Those include making districts compact, minimizing precinct (voting tabulation district) splits, and avoiding splitting municipalities within county boundaries.

We sought to make more of the currently used criteria stricter and, where possible, use numeric targets, and test what impact these changes would have on district mapmaking. For example, a congressional map should have no more than 13 split precincts. One limitation is redistricting criteria often conflict, making drawing an “optimal” map impossible.

We found that the criteria adopted by the North Carolina General Assembly were not written strictly enough to constrain legislators from gerrymandering districts. Of course, the congressional and state Senate maps drawn under the General Assembly’s criteria failed to meet the standards established in this study. What was surprising is that neither the court-ordered congressional and Senate remedial maps drawn by the General Assembly nor the congressional map drawn by three court-appointed special masters met those criteria. (We did not consider North Carolina House maps because the court was considering only congressional and Senate maps in the second hearing of the Harper v. Hall case when work on this study began.)

We recruited 15 student participants from North Carolina State University to draw maps under the standards established in this report. Using strict redistricting criteria made drawing maps more difficult but not impossible. Most participants were able to draw Senate maps that could be used for evaluation. The congressional maps proved to be more difficult and only four participants were able to successfully complete them. With a little more time, most or all of the participants could have produced compliant congressional and Senate maps.

Most of the maps created in that experiment were in the expected normal range of partisan outcomes established by prior research and expert legal testimony. They were all responsive to shifts in partisan support with sufficient toss-up or “swing” districts. Further studies should be done to determine the full extent of the impact of using stricter redistricting criteria.