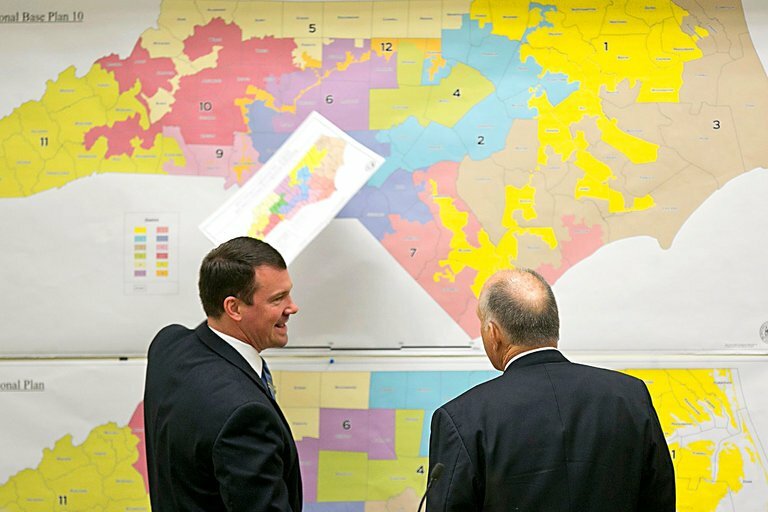

I appeared with former North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Bob Orr in a news segment on a newly filed redistricting lawsuit in November of 2023 (starting at 2:47). Despite our differing perspectives, we disagreed less than I thought we would. We both agreed that plaintiffs in that and other lawsuits would struggle to find grounds to overturn the new General Assembly and congressional maps.

A Quest for a “Successful Theory” Against Partisan Gerrymandering

Early in the talk, Orr said, “Because of the uncertainty around Section Two (of the Voting Rights Act) litigation at this point, I think folks looking at filing other suits are sitting around trying to strategize and figure out ‘what kind of successful theory can we put out there’ that would potentially get an injunction and stop the primaries temporarily.”

Little did I know that Justice Orr would be one of those trying to figure out such a successful theory to overturn the new maps. But that is what he did, leading a lawsuit that seeks to overturn the maps as violating the North Carolina Constitution.

The “major question of first impression” he and his colleagues want the North Carolina court system to answer is whether the state constitution requires “fair” elections:

Plaintiffs, individually, and on behalf of all the citizens of North Carolina contend that they are guaranteed “fair” elections or else the other constitutional guarantees are of little or no value and that the elections in specific districts as set forth below violate their constitutional right to fair elections.

That seems to directly confront North Carolina Supreme Court Chief Justice Paul Newby’s 2022 statement, “We have ‘free.’ We don’t have ‘fair.’” Newby was referring to Article I, Section 10 of the North Carolina Constitution, which states, “All elections shall be free.” That clause has been interpreted to mean that voters are free to vote as they wish from among the choices on the ballot or that it cannot be too onerous for candidates to get on the ballot.

What is “Fair” Redistricting?

Indeed, the suit’s first request for relief is for the courts to declare “an unenumerated constitutional right to fair elections.” But what does “fair” mean in the context of redistricting? Let’s go through the complaint to see.

Page 2: “Plaintiffs, individually, and on behalf of all the citizens of North Carolina contend that they are guaranteed “fair” elections…”

Page 3: “Plaintiffs contend that the right to “fair” elections is an unenumerated right…”

Page 3 again: “The Plaintiffs seek declaration of their constitutional right to “fair” elections in North Carolina…”

“Fair” is written 33 times in the brief, 19 in quotation marks. “Unfair” or “unfairly” is written a further ten times.

OK, but again, what does “fair” mean in this lawsuit?

We don’t find out until page 25 of the 29-page complaint (paragraph 95, to be exact). They define it as a government intentionally taking an action that affects an upcoming election and…

the governmental action at issue gives a specific political party or candidate a determinative advantage in the election by intentionally “apportioning” voters favorable to that specific political party into the specific district or “apportioning” voters unfavorable to that specific political party out of the specific district.

In other words, they claim that the North Carolina Constitution bans partisan gerrymandering.

Old Wine in a New Wineskin

That is not new. The North Carolina Supreme Court dealt with it just last year in Harper v. Hall when the court ruled, “There is no judicially manageable standard by which to adjudicate partisan gerrymandering claims.”

The court was even more specific in Stephenson v. Bartlett, which was decided two decades ago. The majority opinion stated that the “General Assembly may consider partisan advantage” when drawing maps as long as they did so “in conformity with the State Constitution.” That indicates that considering partisan advantage (AKA: gerrymandering) when drawing districts is not, in and of itself, unconstitutional.

(Orr was on the North Carolina Supreme Court for Stephenson. In his partial dissent, he also wrote that the General Assembly could use “partisan considerations — so long as such use does not result in a violation of the mandatory criteria” in federal law or the North Carolina Constitution. Again, that indicates gerrymandering by itself is not unconstitutional.)

I sympathize with Orr’s opposition to partisan gerrymandering and co-wrote a report on limiting gerrymandering in North Carolina. But something is not unconstitutional just because you don’t like it.

It is hard to imagine how Orr and his colleagues expect to prevail with this lawsuit. Given that fact, any guess about what they hope to accomplish would be purely speculative.