Energy poverty is a serious issue. Research shows that higher energy prices cost lives. The U.S. Energy Information Agency showed in 2018 that one in three families struggled to pay energy bills, and one out of every five families had to forego food or medicine to do so.

Those findings were published in 2018 based on 2015 results. The U.S. economy was well in recovery then. Times were good.

But even then, energy poverty was bad for poor North Carolinians. In 2018, Bjorn Lomborg wrote in The Wall Street Journal:

Economists consider households energy poor if they spend 10% of their income to cover energy costs. A recent report from the International Energy Agency shows that more than 30 million Americans live in households that are energy poor—a number that is significantly increased by climate policies that require Americans to consume expensive green energy from subsidized solar panels and wind turbines.

People of modest means spend a significantly higher share of their income paying for their energy needs. One careful study of energy usage in North Carolina found that a lower-income family might spend more than 20% of its income on energy. Among people with incomes below 50% of the federal poverty line, energy costs regularly consumed more than a third of their budgets.

This problem will be worse in the post-COVID economy. Electricity is a basic human need. That’s why state law on electric utilities required least-cost, reliable electricity — that is, in the words of the statute, “adequate, reliable and economical utility service to all of the citizens and residents of the State” and “the least cost mix of generation and demand-reduction measures which is achievable.”

Regardless, North Carolina policymakers have been making expensive decisions in energy policy for years. That was bad enough when times were good. Now it’s worse.

North Carolina’s poor electricity consumers especially need state policymakers to take decisive actions to uphold the standard of least-cost, reliable electricity. Here are several ways to do that.

-

Let PURPA contract rates to qualifying renewable energy facilities vary according to market conditions and be revisited every 1-2 years, rather than be fixed for 10 years

Because of how North Carolina interprets the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 (PURPA), the state requires the highest rates and the longest contracts (10 years at fixed rates) in the Southeast for solar energy. Exorbitant contracts plus the Renewable Portfolio Standards purchase mandates, generous incentives, and huge property tax abatements made this state “second in solar.”

Research from the Edison Electric Institute in 2019 estimated that Americans are having to pay $2.7 billion more for solar power because of PURPA contracts forcing utilities to buy solar power above the competitive market rate for solar power. North Carolina, meanwhile, is home to 60 percent of all PURPA-qualifying solar facilities in the nation. We have well over half the nation’s high-cost solar facilities, and we’re giving them the region’s longest contracts, fixed at the region’s highest rates? The math for North Carolina energy consumers isn’t pretty.

-

Place a moratorium on new solar and wind facilities and incentives until further study

New solar and wind facilities (which aren’t efficient or dispatchable) create expensive grid interconnection problems and are well over twice as expensive as existing natural gas plants and nearly three times more expensive than existing nuclear power plants, both of which are efficient and dispatchable.

But media, ideologues, and special interests have created the popular misperception that renewable energy facilities (and any cronyism that supports them) are critical to improving the state’s environment, taking it as a given that it’s getting progressively worse. The planet’s demise has consistently been “ten years away” in living memory. As a result, a large plurality of North Carolinians polled last year actually thought North Carolina’s environment was getting worse.

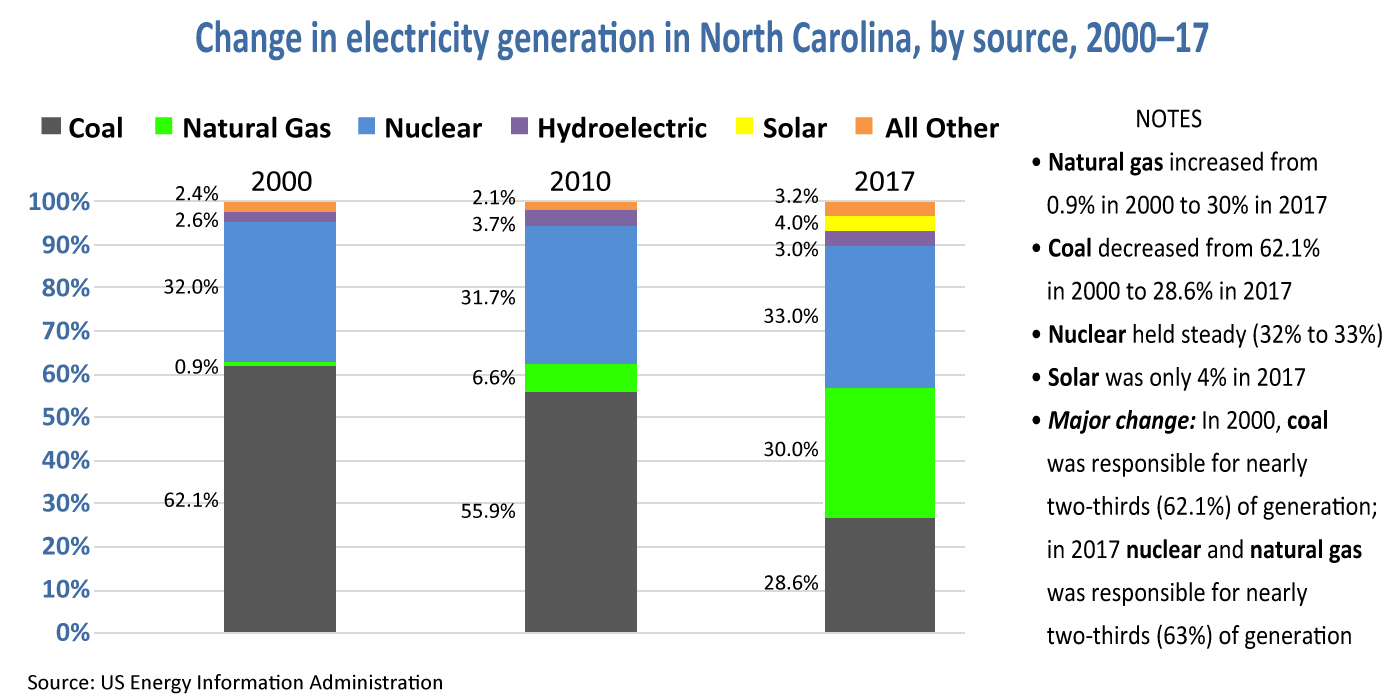

In fact, North Carolina’s emissions from energy generation have fallen dramatically all century as utilities have changed over more to natural gas and nuclear generation (see chart). Solar’s impact is too small to register.

-

Promote the retention of existing nuclear plants, which are least-cost, zero-emission sources of electricity

Despite North Carolina’s two decades of falling energy emissions, Gov. Roy Cooper has developed a “Clean Energy Plan” in consultation with 164 “stakeholder” organizations. Notably, out of all those groups, only 7 percent considered “affordability” a value to prioritize in developing this energy plan.

That’s not a good sign for North Carolina energy consumers about to enter an economy wrecked by months of shutdowns, with shocking numbers of them having been thrown out of work.

In the next few years, Duke Energy will begin seeking license renewals from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to extend the lives of North Carolina’s nuclear fleet. The last thing North Carolina energy consumers need is for state policymakers to cause power generation to shift to costlier sources and make nuclear seem expendable. (That would lead to increased emissions, also.)

Prior to the tsunami and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, Japan and North Carolina received roughly the same proportion of energy (30 percent) from nuclear generation, but afterwards, Japan shut down all 54 of its nuclear power plants even though only 15 were at risk from tsunamis. Now Japan is the second largest net importer of fossil fuels in the world, and electricity prices increased by as much as 38 percent.

In 2019, a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper found that the higher electricity prices that resulted from shutting down all nuclear power in Japan caused more deaths than the nuclear accident that prompted the decision.

Affordability in energy not “a value to prioritize”? To some, it is a matter of life or death.

Conclusion

As North Carolina enters the stark post-COVID economy, state law already has the right standard to keep energy poverty from becoming worse than it otherwise would be: least-cost, reliable power at the flip of the switch. State policymakers must take decisive actions to restore that standard. This is no time for special interests hawking inefficient, unreliable, expensive power.

For more information, see: