- Energy poverty is already a problem in North Carolina

- The poorest families expend over 20% of their household income just for electricity

- Gov. Cooper’s desire for building 8 gigawatts of offshore wind in North Carolina would worsen this problem by increasing residential electricity bills by $400–$500 per year

On February 22, 2022, The Pilot of Southern Pines reported on local families struggling to pay for electricity price increases. The article began:

Emily Jessup didn’t know what to expect when her mother-in-law called to tell her husband that the January power bills were in. She had noticed that the December bill had already been higher than usual — about $200 compared to the normal $170 to $180. But she never thought her January bill would go up by almost another $100.

“When I got that bill,” she said, “I wanted to cry.”

The Vass resident is pregnant with a second child. She works but is also putting herself through school, while raising her 2-year-old daughter with her husband. She lives in a small single-wide trailer and gets her electricity from Duke Energy.

Imagine paying $300 to heat a space as small as a single-wide trailer — and having to rearrange your budget to do so when your circumstances are that you’re living in a single-wide trailer, working, putting yourself through school, and hoping to better things for your growing family. Imagine all that being the case before the utility begins greatly increasing rates to pay for the governor’s exorbitant choice of high-cost yet unreliable electricity generation.

This research brief is the next in a series examining the issues raised in the recent John Locke Foundation policy report, “Big Blow: Offshore Wind Power’s Devastating Costs and Impacts on North Carolina.” The issue in the spotlight here is the critical problem of energy poverty. The recent example above shows it’s already a problem here. But energy poverty would be made worse in North Carolina from the electricity price hikes that people would face with building and maintaining 8 GW of offshore wind facilities.

Energy poverty in North Carolina

The report estimates electricity price increases to North Carolina residential customers of around $400–$500 extra per year. Meanwhile, commercial electric customers (local businesses) would face increases of $1,600–$2,000 extra per year, and industrial customers would face increases of $48,000–$60,000 more per year. Those last two classes of ratepayers are the state’s employers.

A recent study estimated that 8 GW of offshore wind production here would cost North Carolinians 45,000 to 67,000 permanent jobs — an outcome that would certainly not help matters for poor North Carolinians struggling to power, heat, and cool their homes.

Low-income households will be hurt most by rising electricity costs because they spend a higher percentage of their income on energy bills than other North Carolina households. Because electricity is a basic human need, not a luxury item, energy poverty is a serious threat to health and incomes of the poor across America. According to the Home Energy Affordability Gap project, home energy is considered affordable up to six percent of household income. Higher than that means home energy is not affordable.

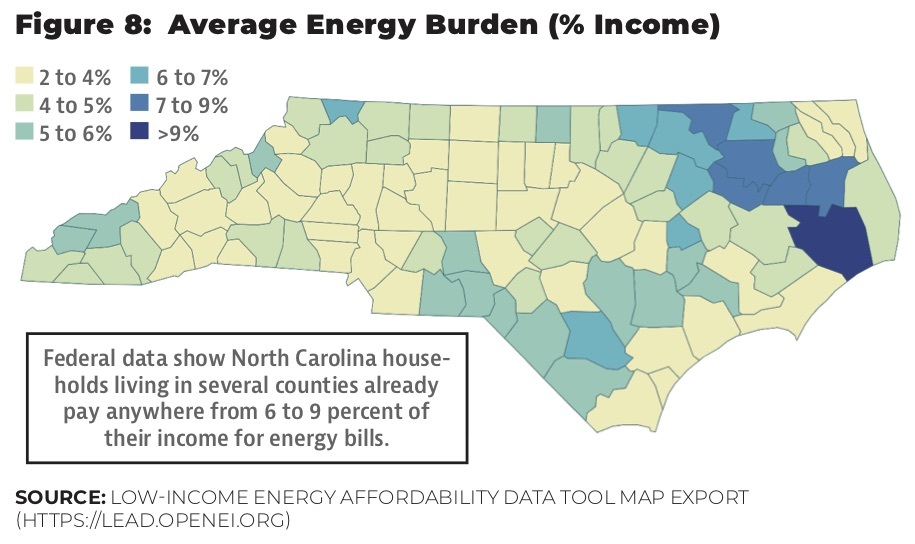

According to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Low-Income Energy Assistance Data (LEAD) program, however, a significant number of North Carolina residents already spend between six and nine percent of their income on energy (see Figure 8 from the report below). This is the situation before their bills would reflect steep increases from incorporating highly expensive offshore wind production.

Writers from The Atlantic to The Wall Street Journal have specifically cited North Carolina as a place where low-income families spend more than 20 percent of their household income on energy costs. In 2021 the poorest families in North Carolina devoted as much as 29 percent of their income to energy costs — money they could therefore not use for food, clothing, rent or mortgage, medication or medical care, savings, or other important ways to help their families. Causing electricity prices to rise even further would reduce people’s purchasing power all the more, leaving the poor with comparably less to pay for life’s other needs.

As if that’s not bad enough, poor families tend to live in less energy-efficient housing, have older, less efficient appliances, and are less able to take advantage of programs to meet government goals of boosting renewable sources of energy (e.g., not only can poor families often not be able to take advantage of net metering and rooftop solar programs, but also they must shoulder the costs of such programs along with other nonparticipating ratepayers). They can’t afford to be energy-efficient, which is why it can cost more to heat a single-wide trailer than a new 3,000-square-foot home.

The state with the most aggressive approach to integrating renewable resources onto its grid, California, also has the nation’s highest poverty rate. Research finds rising electricity prices there to be a contributing and growing factor “disproportionately impact[ing] lower- and middle-income families who lack the disposable income to absorb the extra costs.”

Rising energy poverty is not just unfortunate; it can be deadly

Energy poverty is not an academic exercise; it can be dangerous. The burden of energy poverty is not stable across the four seasons; instead, it is at its worst during temperature extremes. So too are blackouts. Families having to economize on heating and cooling bills during temperature extremes place themselves in greater danger (beyond the obvious). Researchers cite “higher risk of respiratory problems, heart disease, arthritis, and rheumatism” as well as risks of carbon monoxide poisoning and other adverse outcomes from seeking alternative sources of relief.

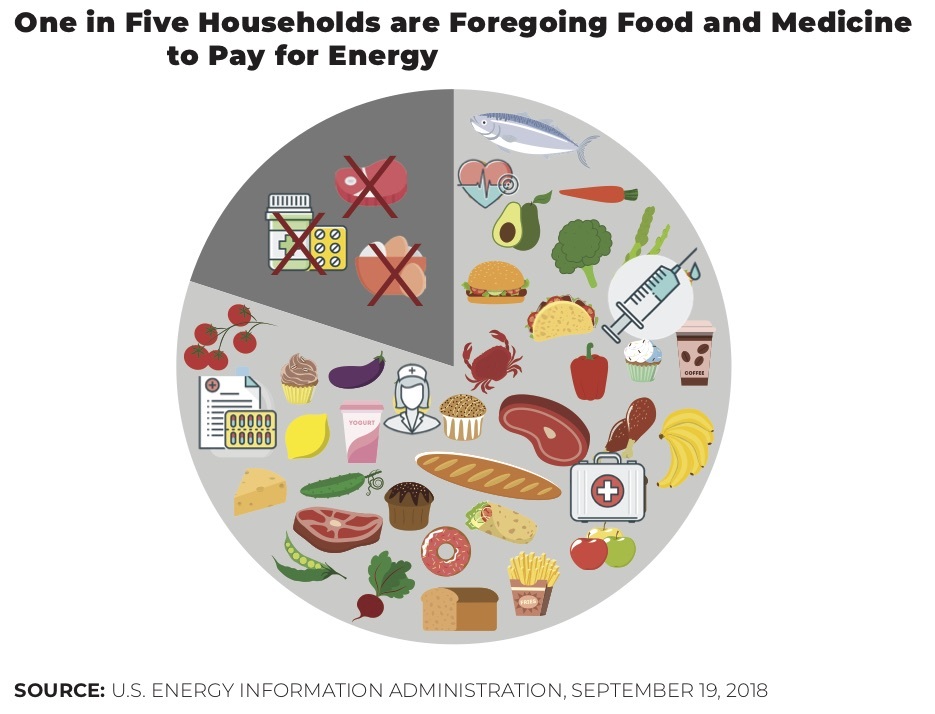

The U.S. Energy Information Administration in 2018 found that “Nearly one-third of U.S. households (31%) reported facing a challenge in paying energy bills or sustaining adequate heating and cooling in their homes.” Worse, the EIA found that “about one in five households reported reducing or forgoing necessities such as food and medicine to pay an energy bill” (emphasis added). Research published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2019 showed that higher energy prices cost lives, and lower energy prices save lives. A retiree in North Carolina struggling to heat his 1,000-square-foot apartment told WRAL his daily choice was this: “Do I stay warm or eat?“

“What else can you cut?” Jessup said. “You can’t cut back on food. You can’t cut back on car payments. … It’s nerve-wracking.”

Those stark choices show up in the article in The Pilot:

With the electricity bills rising, Jessup said there’s little money left over at the end of the month. She said her husband jokes about having to take out a loan just to pay the power bill if it keeps skyrocketing.

“My biggest fear is what if it keeps going up and it can’t stop — what else can you cut?” Jessup said. “You can’t cut back on food. You can’t cut back on car payments. … It’s nerve-wracking, ’cause you don’t know what’s going to happen next.”

Turns out there is something we can cut back on. As explained in our “Energy Crossroads” report, we don’t have to force expensive electricity generation choices on people when less expensive options exist that would also reduce CO2 emissions.