- A North Carolina group says they have found numerous duplicate voter registrations, but election officials have not acted on their findings

- A pair of federal lawsuits set parameters for how and when citizens can challenge voter registrations

- The General Assembly should streamline the process for challenging duplicate registrations

The North Carolina State Board of Elections (SBE) says maintaining clean voter registration rolls is essential because it “ensures ineligible voters are not included on poll books, reduces the possibility for poll worker error and decreases opportunities for fraud.”

To that end, county election officials regularly remove registrations when they receive reports that registrants have moved, died, or been convicted of a felony.

There is one group, however, who says that county boards of elections are insufficiently clearing another form of clutter in voter registration rolls: duplicate registrations.

Group Wants Duplicate Voter Registrations Removed. State Elections Board Says They Are Doing What They Can.

Carol Snow is with the North Carolina Audit Force (NCAF), a group that uses publicly available voter registration data to “verify it coincides with the truth.” She said via email that NCAF had found numerous likely duplicate registrations that matched on three elements: name, address, and birth year. By requiring a match on all three elements, they reduced the risk of false positives by people who may match only two elements (such as Tom Jones Sr. and Tom Jones Jr., who live together). Those matching registrations have been assigned different voter registration and NCID numbers, meaning they would not get caught in a search based on those numbers.

Snow said they also found evidence of duplicate registrations being used for voting. I looked at two examples they pointed out, one each in Columbus and Mecklenburg counties, in the 2020 general election absentee voter files published by the SBE. In both cases, the “ballot return status” column of the data indicates that ballots from both their registrations had been accepted.

SBE public information director Patrick Gannon told me that a system is in place for removing duplicate registrations and that “76,000 voter registrations have been removed with ’duplicate’ as the reason.” Most of those duplicate registrations are due to people moving to a new county and using different information (such as a newly married woman providing another name) when registering.

That kind of duplication is a different issue from what Snow identified.

Gannon also shared that citizens can provide SBE officials with data to help the board with its effort to “dedupe” voter registrations (i.e., to remove duplicate registrations):

With this information, the State Board can evaluate whether these potential duplicates are already identified using existing data checks, which is often the case. And if they are not, we can evaluate them and consider additional ways to catch them through additional data queries in the future, as staffing and resources permit.

So, at least part of the persistence of duplicate registrations is that election officials do not have the resources to remove them quickly.

Another part is that citizens cannot take their findings to county election boards and expect action from those officials. In Numbered Memo 2022-05, the SBE told county election boards that “board-initiated challenges shall not be based on lists provided by outside groups or individuals” — due to concerns that those groups or individuals may have an “interest in the outcome of the election” and would provide biased information.

That leaves ordinary citizens with only one option. Gannon wrote that citizens can address duplicate registrations through the voter challenge process, in which they submit challenge forms to their county board of elections.

That process has its own set of problems, however.

Legal Brackets for Data-Based Voter Registration Challenges

Two legal cases set the parameters for challenging voter registrations based on data (as opposed to challenges based on personal knowledge of the registrant).

A 2016 federal court ruling overturned the removal of several hundred registrations based on challenges from individuals working with data from the Voter Integrity Project (VIP).

U.S. District Court Judge Loretta Biggs wrote that the practice violated federal law:

There is little question that the county boards’ process of allowing third parties to challenge hundreds and, in Cumberland County, thousands of voters within 90 days before the 2016 General Election constitutes the type of ‘systematic’ removal prohibited by the National Voter Registration Act.

Biggs called the challenge and removal process “insane” during a hearing, adding, “It almost looks like a cattle call, the way people are being purged.”

A more recent case upheld the legality of data-based registration challenges. District Court Judge Steve C. Jones ruled on January 2 that a group called True the Vote’s effort to “challenge the eligibility of hundreds of thousands” of registrations in Georgia did not constitute illegal voter intimidation. In short, groups using data to assess and challenge voter registrations do not violate voters’ rights.

These cases create a legal bracket in which people can use data to challenge voter registrations except during the three months before a primary or general election.

Challenging Duplicate Registrations Is a Challenge

There are a couple of problems that must be addressed to make challenges of duplicate voter registrations a viable option.

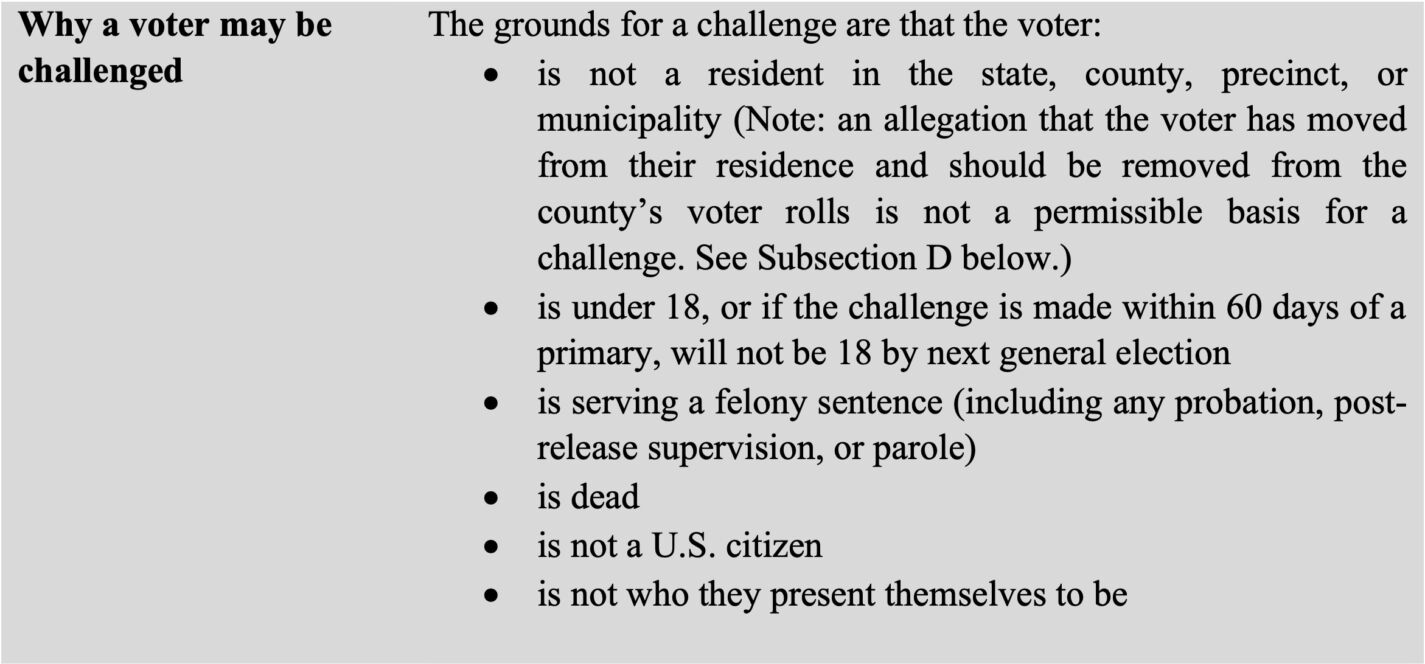

The first problem is that duplicate registrations are not currently listed as one of the grounds for a challenge, as seen in the detail of the voter challenge guide below.

Detail of the North Carolina State Board of Elections’ Voter Challenge Procedures Guide section on voter registration challenges

Gannon wrote that the categories are set by law (GS § 163-85 (c)) but that challengers could use one of the existing challenge categories on an ad hoc basis:

[O]ne option could be, “That the person is not who he or she represents himself or herself to be.” In other words, the same individual has two separate registrations, and they are actually registrant NCID # 1234, not NCID # 5678, the latter of which is based on outdated information pertaining to that individual.

Using existing challenge categories to challenge duplicate registrations is not mentioned in the SBE’s Voter Challenge Procedures Guide, meaning that citizens (and at least some election officials) may not be aware of that option. The SBE should update the procedure guide to specify the challenge procedure for suspected duplicate registrations.

There is another concern for citizens who want to challenge duplicate voter registrations: the threat of lawsuits. Snow doubted that NCAF would organize such challenges over fears that they would be targets of lawsuits like those against VIP and True the Vote. She wrote that, even if plaintiffs have no case, “it will cost us money to hire an attorney to defend ourselves.”

The Best Solution to Duplicate Registrations Is to Streamline the Law

The best solution for both concerns is for the General Assembly to amend G.S. § 163-85 (c) by adding a category specifying that citizens can challenge registrations they believe are duplicates.

Updating the law is more satisfactory than having the SBE try to force the round peg of challenging duplicate registrations through the square hole of the current law. Creating a category in the law specifically for challenging duplicate registrations would also provide greater legal protection for citizens who make such challenges.

For addressing the problem of how citizens can confront duplicate voter registrations, there is no substitute for General Assembly action.