A legal challenge to the state Senate maps was filed just before the Thanksgiving holiday last week, questioning the state’s compliance with the Voting Rights Act. With candidate filing set to begin Dec. 4, the plaintiffs requested the court to expedite a preliminary injunction. Federal court judge James Dever denied the motion to expedite the injunction, citing the plaintiffs’ lack of justification in allowing defendants only one business day to respond to a motion filed the day before Thanksgiving.

Judge Dever rejected the plaintiffs’ motion solely on the grounds of the expedited timeline the plaintiffs had requested. While the preliminary injunction is unlikely to be ultimately granted, the process is still ongoing and will simply follow the standard timeline for such motions before federal courts.

Even though the case has been pulled off the fast track, it’s important to illustrate the critical question the court has been asked regarding Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) and the state’s unique redistricting rule known as the “Stephenson Criteria.” Stephenson v. Bartlett is a compromise between two provisions in the North Carolina State Constitution: the rule that districts must maintain nearly equal population and the provision that “no county shall be divided in the formation of a senate [or house] district.” This requires counties to be clustered based on the population needed to create Senate or House districts.

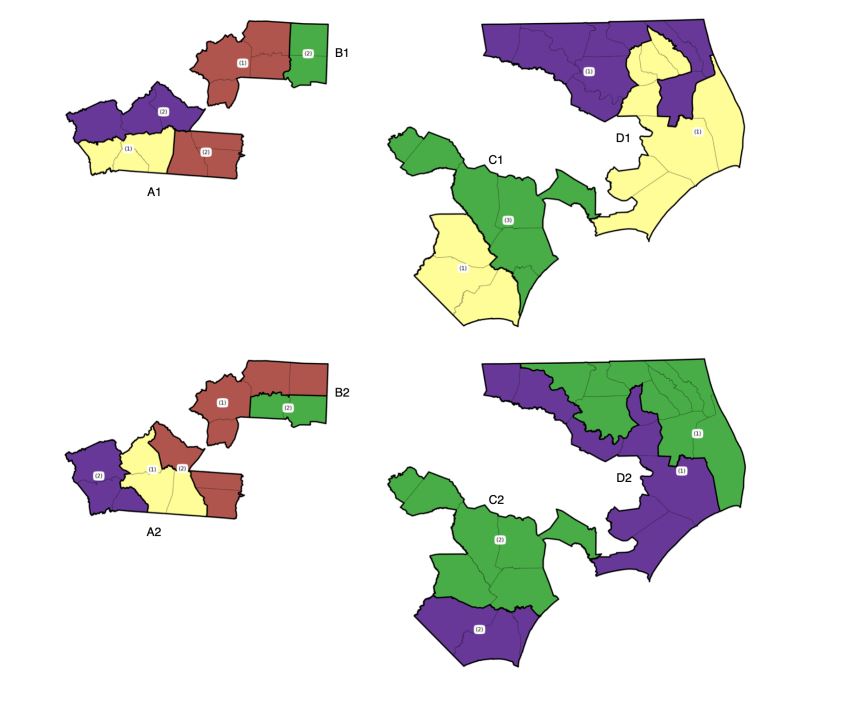

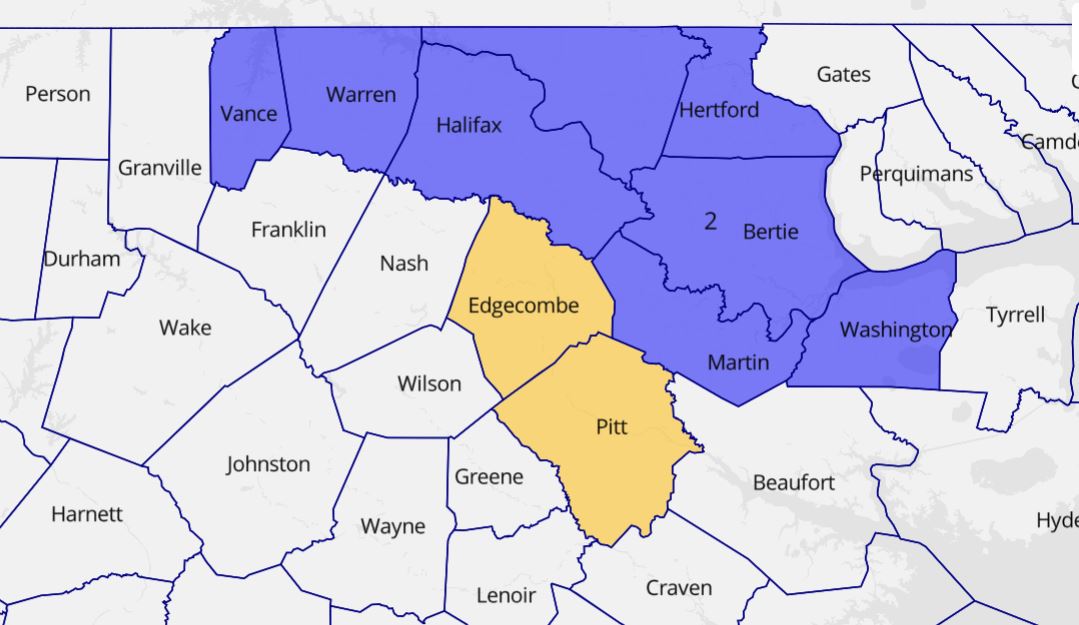

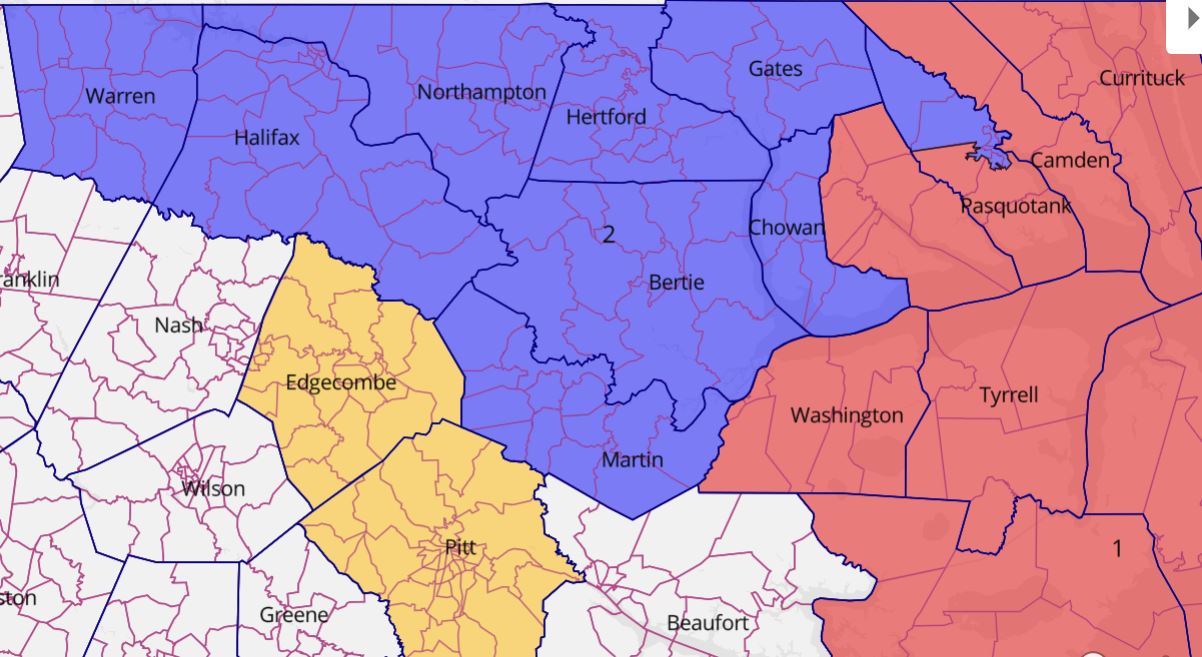

The two districts plaintiffs are challenging are Senate Districts 1 and 2 in the northeastern corner of North Carolina. These districts can have only one of two variations under Stephenson. Map drawers must take either option D1 or D2 from Figure 1; no other variation is allowed under Stephenson. The 2022 North Carolina Senate elections were conducted under the D1 clustering, while the current maps utilize the D2 configuration.

Plaintiffs, claiming the current map is a racial gerrymander, argue that the county groupings violate VRA requirements and that a majority-minority district should be drawn along the northeastern “black belt counties.” Plaintiffs argue that North Carolina meets the Gingles criteria and should be required to create an additional majority-minority district. However, courts have rejected the argument that the state meets the Gingles requirement of racially polarized voting in Cooper v. Harris, Common Cause v. Lewis, and recently in the Harper v. Hall III decision.

The plaintiffs have proposed two separate maps for the court, both requesting that the majority-black Edgecombe County not be included in the “black belt” district. Instead, they request that the Pitt and Edgecombe cluster be maintained.

Map A would overtly break apart the Stephenson criteria by creating a majority-minority district out of three separate clusters. The proposed majority-minority district would create a 51.47 percent black district by combining Washington, Martin, Bertie, Hertford, Northampton, Halifax, Warren, and Vance Counties.

Under Stephenson, there are two problems with this configuration. Vance County must be paired with Franklin and Nash to create a single Senate district, and Washington and Bertie Counties can never be in the same district. If the court accepted this proposal, it would have a cascading effect on the other county clusters throughout the state. This could force a redrawing of most, if not all, of North Carolina’s Senate districts.

Almost as if to resolve this cascading effect in Map A, plaintiffs proposed Map B. They claim that a district can be reconfigured to adhere to Stephenson while also creating a majority-minority district. While this change would not have the cascading effect that Map A would create, it’s wrong to say that this is either a majority-minority district or that it adheres to Stephenson.

Plaintiffs acknowledge in their court filings (page 12, section 49) that in the “majority-minority” district created in Map B (see Figure 3’s district 2), “[t]he Black voting age population for this demonstration district (B-1) is slightly less than 50%,” but try to slidestep the problem by stating “the Black citizen voting age population is 50.19%.” VRA compliance traditionally has utilized black voting age population, not black citizen voting age population. Utilizing this sub-criteria would deviate from court precedents.

As for Map B’s compliance with the Stephenson criteria, while Senate clusters not affiliated with Districts 1 and 2 would remain intact, it does break from the criteria by combining both single-senate-district clusters into a two-senate-district cluster. This breaks from the Stephenson rule of taking only the minimum number of counties necessary to create a district. Map B produces an unnecessary division in Pasquotank County while failing to create a majority-minority district.

If the court accepted the plaintiffs’ argument on the Senate maps, this would have long-term effects on how we create county clusters under Stephenson. However, the court is unlikely to accept the plaintiffs’ arguments.

Not only would the court have to go against prior assessments of racially polarized voting in North Carolina, but it would also have to go against the ruling of Cooper v. Harris. My colleague Dr. Andy Jackson recently pointed out that the plaintiffs’ use of race as the predominant factor in drawing maps runs afoul of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Just this violation makes it unlikely that federal courts will accept the plaintiffs’ argument.

While this case is unlikely to overturn the current state Senate map, more lawsuits will likely come. Long-time Democratic lawyer Marc Elias has indicated additional suits are likely coming regarding North Carolina’s districts.

It’s safe to say North Carolina will hear more Gingles throughout this holiday season.