Yuval Levin questions politicians’ unwillingness to focus on building winning electoral coalitions.

In the spring of a new president’s second year in office, political junkies know all too well what to expect from the midterm elections.

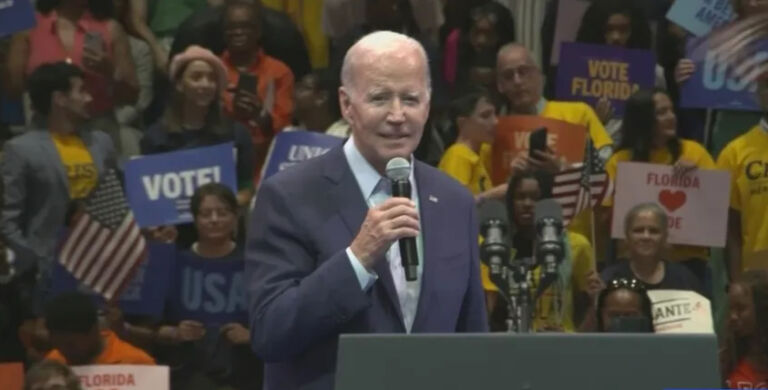

A president (of whatever party), elected largely thanks to public distaste for his opponent, came in with his party in control of Congress and intent on not wasting an opportunity for transformative policy change. For all his talk of building new coalitions, he focused on the priorities of his party’s core activists, and by now it’s pretty clear that most voters don’t love what they see. The only way his party will avoid losing at least one house of Congress is if the other party somehow makes itself even more obnoxious. The question for November is whom the public will like less.

Something like this has been the pattern of our politics for three decades now — long enough that we rarely stop to wonder much at just how strange it is or how we might change it. Neither party does much to expand its appeal or its coalition. Both double down on the voters they can count on, hoping they add up to a slim, temporary majority. If that doesn’t work, they just do it again.

For political parties, whose very purpose is to build the broadest possible coalitions, such behavior is malpractice. So why has it persisted for so long? Why is public disaffection not pushing politicians to change their strategies or their agendas and seek durable majorities?

The very fact that voters are unhappy with both parties makes it hard for either one to take a hint from its electoral failures. Even more than polarization, it is the closeness of elections that has degraded the capacity of our democracy to respond to voter pressure. In an era of persistent, polarized deadlock, both parties are effectively minorities — but each continues to think it is on the verge of winning big.