- Innovators move fast, but bureaucracies are slow, and regulations to protect consumers can make them worse off by protecting old ways from new products and services

- Regulatory sandboxes waive certain regulatory obstacles on a trial period for fast-emerging products and services, helping speed innovation in a way that benefits consumers and the economy

- Companion bills in the General Assembly would create a regulatory sandbox in North Carolina for financial and insurance products and services

Imagine telling someone in the 1970s that in 50 years, what we call a phone would mean a watch, a camera, a calculator, newspaper, a television, a directory, a concierge, a post office, a secretary, a personal library, an arcade, a bank, a personal computer about a billion times faster than anything currently known — oh, and a personal telephone, among countless other things — and that it would fit in your pocket.

Innovation moves fast, at a pace that often can only fully be appreciated in hindsight. Billions of creative minds restlessly pursuing better, newer, cheaper, visionary, next-generation innovation is the enterprising forefront of Julian Simon’s Ultimate Resource at work. It happens faster than organizations can change. It certainly moves faster than bureaucracies. It’s why a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) workshop on the sharing economy urged a cautionary approach to regulation, “only when there is evidence regulation is needed,” “narrowly tailored,” and “no more restrictive than necessary.”

Don’t get in the way if you don’t have any idea what you’re trying to stop.

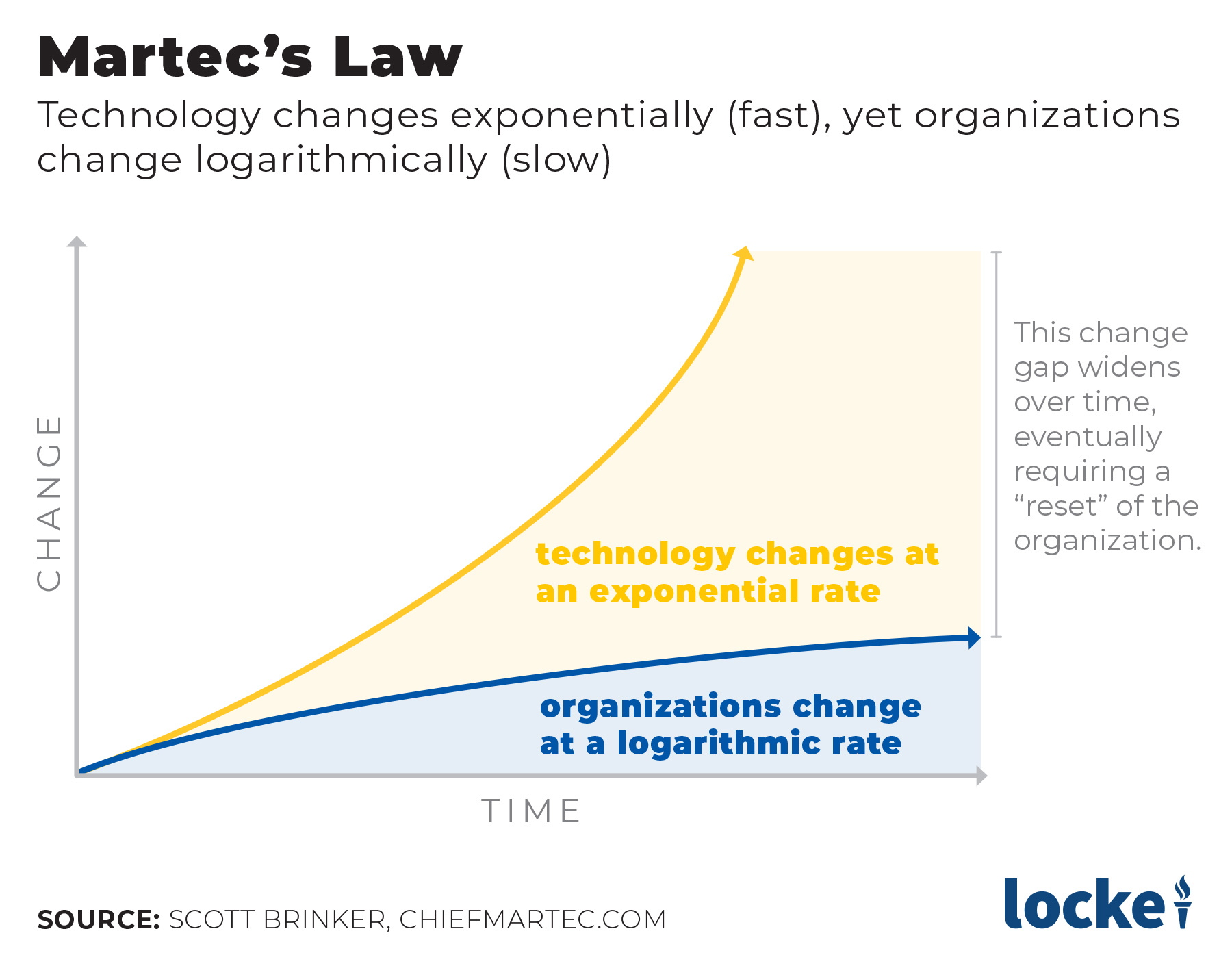

In 2013, marketing technologist Scott Brinker introduced the concept of what he called Martec’s Law: technological change is exponential, but organizational change is logarithmic. That’s more math terms than one might prefer in a sentence, but what it means is innovative change is rapid and gets quicker as it goes, but for a company (or regulating agency) organizational change comes about gradually and slowly.

It is for those reasons that Locke’s recommendations to North Carolina policymakers discussing emerging ideas start with resisting the urge to regulate.

Testing new consumer products and services in a “regulatory sandbox”

The General Assembly is currently debating a “North Carolina Regulatory Sandbox Act.” Companion bills have been filed in both chambers (Senate Bill 470 and House Bill 624). The legislation would establish a “regulatory sandbox” for financial and insurance products and services that rely on new and emerging technology. It would be supported by a new North Carolina Innovation Council.

What’s a regulatory sandbox? It’s a colorful phrase for a new administrative approach to regulation when it comes to newly emerging products and services. The idea exhibits the kind of mutual respect for innovation and regulation discussed above.

As described in RealClear Policy, “Regulatory sandboxes are closed testing environments where firms can experiment with innovative new products, services, and business models for a limited period of time, under some form of modified regulatory environment.”

The idea originated in the United Kingdom in 2014 specifically for financial tech (fintech) companies. By 2018 it was considered a huge success, and regulatory sandboxes started cropping up around the world (Singapore, Abu Dhabi, Denmark, Hong Kong, etc.) as well as the U.S. (Arizona, Utah, and Wyoming). South Korea built its regulatory sandbox for every industry, and Utah, whose regulatory sandbox started with finance and insurance, just did the same.

Existing regulations can be burdensome, but they can also be particular obstacles to new ideas, and (see Martec’s Law) they can become entrenched and backward-thinking. At their best, regulations protect consumers, but sometimes they can protect the old ways and resist innovation. When that happens, consumers end up worse off, and so does the economy.

The idea of a regulatory sandbox is to strike a balance between protecting consumers from bad products and services and helping consumers with more choice, competition, and emerging products and services.

Details of the proposed sandbox for NC

The proposed regulatory sandbox program in North Carolina would be for entities offering new financial or insurance products — or new ways of offering products — that could substantially use or incorporate new or emerging technology, including blockchain technology. The new Innovation Council would encourage participation in and application to the program. It would evaluate applications according to the nature of the entities’ product, its innovation, its potential consumer risks, what consumer protections and complaint resolution the entities offer, their business plan and capital, among other considerations.

Successful applicants would receive a waiver from certain state regulations for 24 months to test out a product or service. They would pay an application fee ($50) and participation fee ($450), they must have a physical presence in North Carolina, and they must pass a criminal background check. The number of consumers for the product or service could be limited, the entity could be required to post a consumer protection bond, and after the sandbox period was complete, the entity would submit a final report to its regulating agency. The entity would have to keep records for at least five years.

Along with keeping in place all applicable criminal or consumer protection laws, the program would require the entity disclose to any potential consumers several things: the names and contact information for the entity, the fact that the product or service is in the sandbox program for temporary testing and is neither endorsed nor recommended by the state or the agency, and instructions on how to contact the agency or Attorney General with complaints or concerns about possible legal violations. These disclosures must be clear and conspicuous in English and Spanish.

As the band Flyleaf sang, “You can only move as fast as who’s in front of you.” Innovations happen quickly, but bureaucracies are slow. A regulatory sandbox in North Carolina would waive certain regulatory obstacles on a trial period for fast-emerging products and services, keeping consumer protections in place. It could speed innovation here in a way that helps consumers and the economy.