This is the first of a three-part analysis of federal asset forfeiture and the threat it poses to property rights and the right to due process in North Carolina. This analysis focuses on one federal asset forfeiture program in particular – the practice of “equitable sharing.” Part One will explain how equitable sharing makes it possible for state and local law enforcement agencies to circumvent the protections against asset forfeiture abuse that are provided by North Carolina’s statutes and by the North Carolina Constitution. Part Two will describe and evaluate what other states have done to address this problem. Part Three will offer specific recommendations for North Carolina.

We are fortunate in North Carolina. Because our statutes and our constitution discourage civil asset forfeiture, our law enforcement agencies have been able to maintain a relatively high level of integrity, and the kind of asset forfeiture abuse that has occurred in other states has been rare. Taking steps to eliminate or curtail federal equitable sharing in North Carolina will help ensure that we keep it that way.

“A civil-liberties debacle and a stain on American criminal justice.”

Civil asset forfeiture is a legal process that empowers law enforcement agencies to confiscate property suspected of having been used for, or derived from, criminal activity. It is a civil action against the property itself, which results in cases with names like “United States v. $16,000”1 or “United States v. 7004 Calais Drive, Durham, NC.”2 The owner of the property need not be charged with, let alone convicted of, committing a crime. In fact, the owner need not even be a suspect, as Mary Ford, the owner of 7004 Calais Drive, discovered when her home was taken because her son was suspected of selling cocaine from the property.3

To recover property seized through civil asset forfeiture, owners must initiate an expensive and time-consuming lawsuit in which they bear the burden of proving that the property was not used or acquired in an impermissible way. Most seizures go unchallenged. Sometimes, no doubt, this is because the property really was used for, or derived from, some criminal activity. But often it is because the value of the property is too small to justify the cost of a lawsuit (which is typically thousands of dollars) or because the owners are ill-informed or too intimidated to assert their rights.

To make matters worse, when owners do undertake the onerous burden of suing to recover the property, the standard of proof is not, as in a criminal trial, “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Instead, the “preponderance of evidence” standard applies. What this means is that to win at trial and keep the property, the government need not present solid and convincing evidence that the property was used for, or derived from, criminal activity. All it must do is persuade a court or jury that its claim is slightly more likely than not. Despite this low standard of proof, in 2014, when The Washington Post looked at hundreds of cases in which property owners had sued to recover their property, it found that in more than 40 percent of the cases, the property owners eventually won in court.4

Mary Ford, the Durham homeowner mentioned previously, was one of those lucky ones. She successfully challenged the taking of her home. As her attorney explains, however, that doesn’t mean that justice was done in her case, or in other similar cases:

Mary Ford had no clue what her son was up to in that house. She got it back, but she had to pay me to do it. It cost her some money, and that’s unfortunate. The government shouldn’t have seized it in the first place. They should have investigated. But they seize first and ask questions later.5

Forcing people who have not even been accused of a crime to spend thousands of dollars to recover their property from the police makes a mockery of the right to due process that is guaranteed by both the United States Constitution6 and the North Carolina State Constitution.7

For many years, civil asset forfeiture was regarded as an archaic relic — something comparable to putting animals on trial for murder.

The practice was revived in the 1970s as a weapon in the War on Drugs, and it was explicitly authorized as a law enforcement tool under the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 (CCCA).8 After the passage of the CCCA, the use of civil asset forfeiture by federal law enforcement agencies increased rapidly. By the beginning of the 21st century, the Department of Justice (DOJ) was collecting and processing millions of dollars of forfeited assets each year, and the annual total increased steadily in the years that followed. In 2014, the DOJ collected and processed assets worth almost $4.5 billion, an amount that exceeded the total value of all the assets stolen by burglars in America in that or any other year.9 In the 10-year period ending in 2016, almost $22 billion in civil asset forfeiture proceeds were deposited into the DOJ’s forfeiture fund10, and that doesn’t fully account for all the assets taken by federal law enforcement during that period. Billions more were deposited into the Department of the Treasury’s forfeiture fund as well.11

Civil asset forfeiture is inherently unjust, not to mention a violation of due process. It is, as one constitutional scholar puts it, “[A] civil-liberties debacle and a stain on American criminal justice.”12 What is worse, it tends to pervert the proper relationship between the police and the public by turning the former into predators and the latter into prey. Allowing law enforcement agencies to self-fund their operations by taking property directly from the citizens creates perverse incentives and encourages abuse. We know from what has happened in other states that these sorts of perverse incentives eventually lead to abuses and a loss of trust between the police and the public.13 The latter is something we can ill afford at a time when relations between the public and the police are particularly fraught.

North Carolina leads in good ways and in bad

Civil asset forfeiture would have been a scandalous affront to Americans’ property rights, and their right to due process, even if its use had been confined to federal law enforcement, but it soon became popular with state and local law enforcement agencies as well. By the end of the 20th century, most states had enacted civil asset forfeiture laws of their own – but not North Carolina. While there are some exceptions,14 under North Carolina law, forfeiture is generally permitted only in the case of property “directly or indirectly acquired as a result of committing a felony,”15 and only when the owner has been convicted of that felony.16

Part of the reason North Carolina has been reluctant to embrace civil asset forfeiture as a law enforcement tool is Article IX, Section 7 of the North Carolina Constitution, which states:

[T]he clear proceeds of all penalties and forfeitures and of all fines … for any breach of the penal laws of the State … shall be faithfully appropriated and used exclusively for maintaining free public schools.17

This provision removes the incentive for asset forfeiture abuse and discourages the kind of predatory policing that has poisoned relations between the police and the public in many parts of the country.

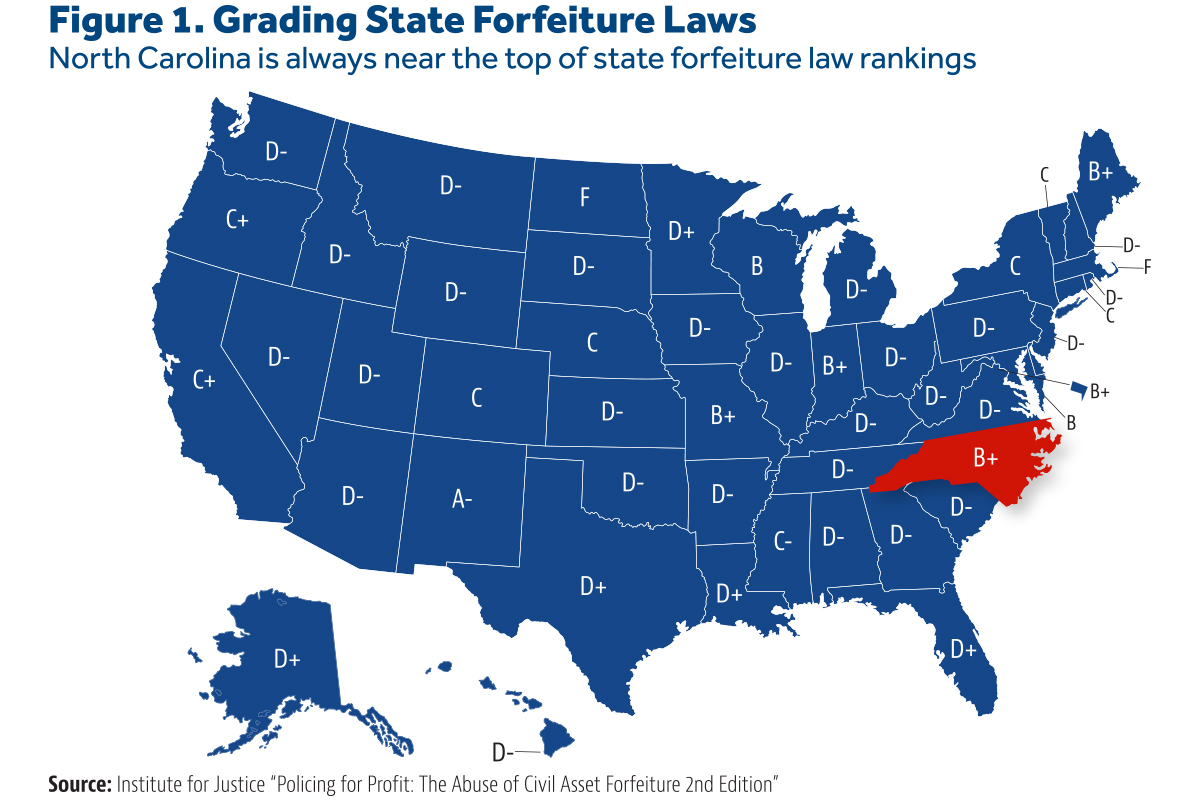

These features of state law have earned North Carolina high marks in repeated editions of the Institute for Justice’s “Policing for Profit”18 report. (See Fig. 1) In 2015, they also earned North Carolina the second highest score in a report by FreedomWorks titled “Civil Asset Forfeiture: Grading the States.”19 North Carolinians can be justifiably proud of our state’s asset forfeiture laws, and we should be grateful that our legislature has exercised such wisdom and good sense.

Unfortunately, when it comes to asset forfeiture, North Carolina has also been a leader in another, less positive, way. For many years, the federal government has encouraged state and local police departments to take citizens’ property without regard for state law at all. Under a policy called “equitable sharing,” federal law enforcement agencies process property seized by state or local agencies and then, after taking a cut for their services – typically 20 percent – they return the remainder of the proceeds to the agency that made the seizure.

Like the rest of the modern federal civil asset forfeiture regime, equitable sharing started in the mid-80s and grew rapidly. By the beginning of the 21st century, state and local law enforcement agencies across the country were collecting hundreds of millions of dollars in equitable sharing proceeds returned to them from the DOJ and Treasury. Since 2011, the total amount of equitable sharing proceeds returned to state and local agencies has exceeded a half-billion dollars every year.20

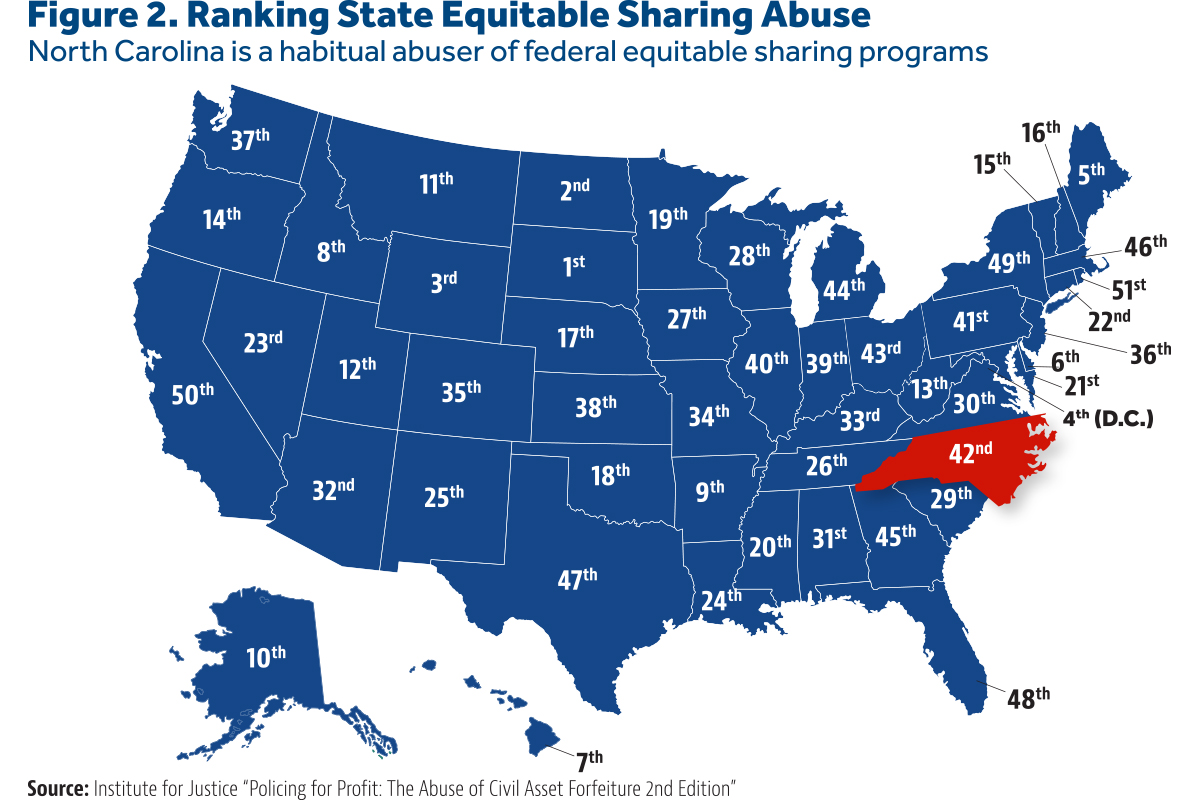

Participation in equitable sharing programs varies from state to state, and, as the Institute for Justice report cited earlier notes, there’s a pattern to the variation: “When civil forfeiture is more difficult and less financially rewarding under state law, law enforcement agencies turn to federal asset sharing instead.”21 This is what has occurred in North Carolina. Between 2007 and 2016, state and local law enforcement agencies in North Carolina collected more than $170 million in equitable sharing proceeds from the DOJ and Treasury.22 In per-capita terms, that number is higher than in most states, and it reflects the fact that North Carolina law enforcement agencies have been particularly aggressive about using equitable sharing to supplement their taxpayer-approved funding. As a result, the Institute for Justice ranks North Carolina among the very worst states when it comes to federal asset sharing.23 (See Fig. 2)

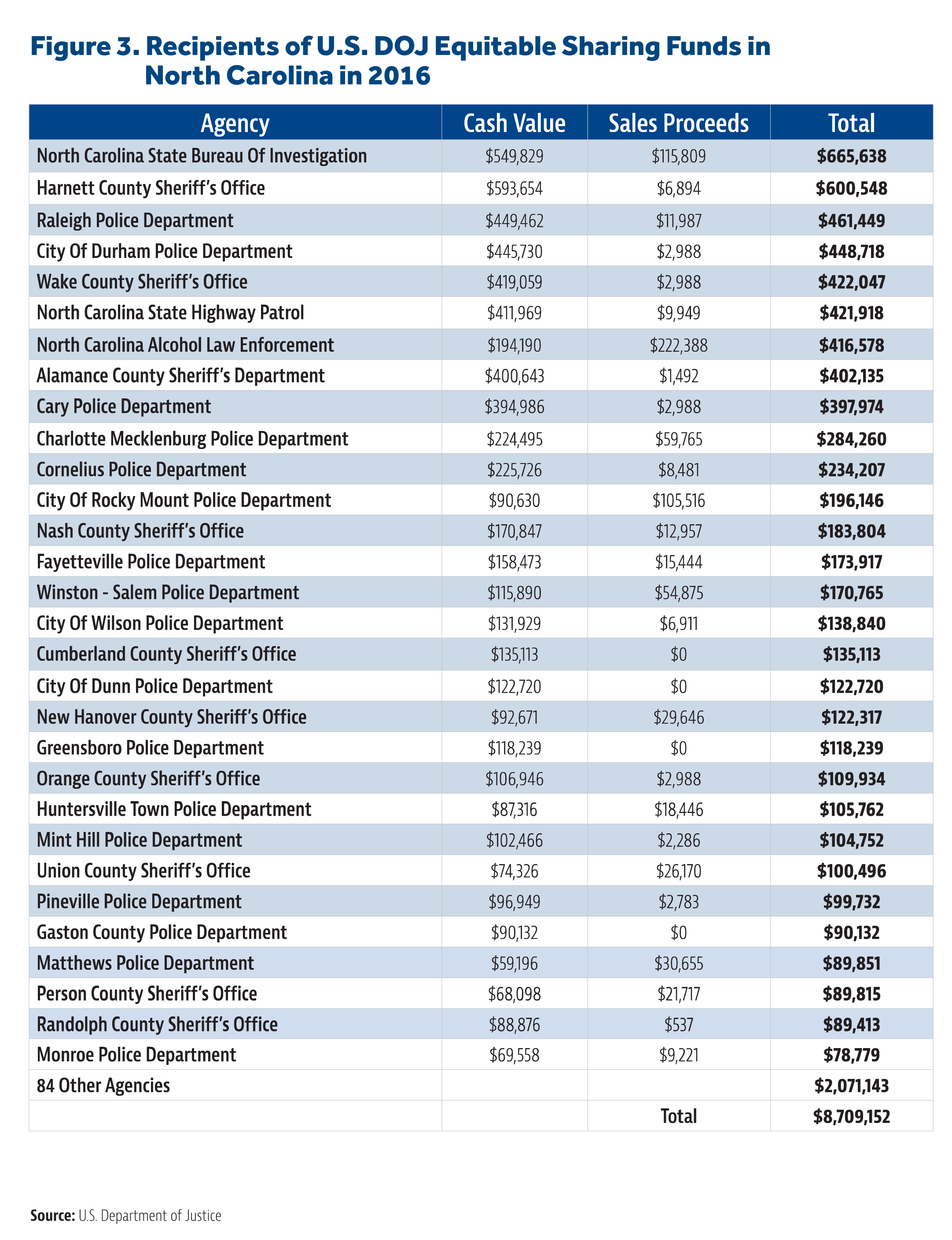

More than 100 North Carolina law enforcement agencies participated in federal equitable sharing programs in 2016, but 30 agencies collected the bulk of proceeds.24 (See Fig. 3) Much of this money may have come from seizures that would have been lawful under North Carolina law, but, unfortunately, because they were processed under federal law instead, there is no way to know. There is one thing, however, that we do know. If any such lawful seizures had been processed under North Carolina law, the proceeds would not have been returned to the agencies that made them; they would, instead, have been appropriated by the counties in which they occurred and used for public education.

Conclusion

The best solution for North Carolina (and for the rest of the country) would be for the federal government to cut back or even abolish all of its civil asset forfeiture programs, including equitable sharing. Over the years, there have been several attempts along those lines. In January 2015, for example, then-Attorney General Eric Holder announced a modest cutback in one rather small part of the DOJ’s equitable sharing program.25 A week later, Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul introduced a bill in the U.S. Senate that would have made much more substantial and permanent cuts.26

Sadly, the policy change announced by Mr. Holder turned out to be modest indeed, and Sen. Paul’s bill went nowhere. In December 2015, the DOJ announced that it was temporarily suspending its equitable sharing program altogether,27 but the program was soon reinstated.28 Since then, Sen. Paul and like-minded members of the U.S. House of Representatives have introduced additional reform measures, but without success.29 And, returning us to exactly where we started, in August, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that he was reversing the modest cutbacks that Eric Holder had made in 2015.30

All of this suggests it would be a mistake to wait for reform to happen at the federal level. Instead, it falls to the states to do what they can under their own state laws to protect their citizens from asset forfeiture abuse. Part Two of this series will describe and evaluate what other states have done along those lines, and Part Three will make specific recommendations for North Carolina.

Unlike many states, North Carolina’s statutes and North Carolina’s constitution discourage civil asset forfeiture. As a result, our law enforcement agencies have been able to maintain a relatively high level of integrity, and the kind of asset forfeiture abuse that has occurred in other states has been rare. Taking steps to eliminate or curtail federal equitable sharing in North Carolina will help ensure that we keep it that way.

Endnotes

1. No. 5:14-CV-656-F (E.D.N.C. 2014).

2. No. 1:14-CV-00079 (M.D.N.C. 2014).

3. Phillip Bantz, “Feds let Durham woman keep house,” North Carolina Lawyers Weekly (August 11, 2014).

4. Robert O’Harrow Jr., Steven Rich, Michael Sallah, and Gabe Silverman, “Aggressive police take hundreds of millions of dollars from motorists not charged with crimes,” The Washington Post, September 6, 2014;

5. James B. Craven, III, telephone conversation with the author, September 7, 2017.

6. U.S. Constitution, amend. 5 & amend. 14, sec. 1;

7. N.C. Constitution, art. 1, sec. 19;

8. Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984., Pub. L. No 98-473, 98 Stat. 1837 (1984).

9. Christopher Ingraham, “Law enforcement took more stuff from people than burglars did last year,” The Washington Post, November 23, 2015.

10. “Reports,” Asset Forfeiture Program, The United States Department of Justice, accessed September 07, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/afp/reports-0.

11. “Annual Reports,” Resource Center, US Department of the Treasury, accessed September 07, 2017.

12. Robert O’Harrow Jr., Sari Horowitz, and Steven Rich, “Attorney General Holder limits civil seizure process that split billions of dollars with local and state police,” The Washington Post, January 16, 2015.

13. Jon Guze, “Lucky to Be Here,” John Locke Foundation, March 24, 2015.

14. See, e.g., North Carolina General Statutes, sec. 20-28.3 (“Seizure, impoundment, forfeiture of motor vehicles for offenses involving impaired driving while license revoked or without license and insurance, and for felony speeding to elude arrest.”).

15. North Carolina General Statutes, sec.14-2.3 (“Forfeiture of gain acquired through criminal activity.”);

16. State v. Jones, 158 N.C.App. 465 (2003).

17. N.C. Constitution, art. IX, sec. 7;

18. Dick Carpenter II, Lisa Knepper, Angela C. Erickson, and Jennifer McDonald, “Policing for Profit,” Institute for Justice, November 2015.

19. Michael Greibrok, “Civil Asset Forfeiture: Grading the States,” FreedomWorks, May 08, 2015.

20. “Reports,” Asset Forfeiture Program, The United States Department of Justice, accessed September 07, 2017; “Annual Reports,” Resource Center, US Department of the Treasury, accessed September 07, 2017.

21. Dick Carpenter II, Lisa Knepper, Angela C. Erickson, and Jennifer McDonald, “Policing for Profit,” Institute for Justice, November 2015.

22. “Reports,” Asset Forfeiture Program, The United States Department of Justice, accessed September 07, 2017; “Annual Reports.” US Department of the Treasury Resource Center. Accessed September 07, 2017.

23. Dick Carpenter II, Lisa Knepper, Angela C. Erickson, and Jennifer McDonald, “Policing for Profit,” Institute for Justice, November 2015.

24. Reports,” Asset Forfeiture Program, The United States Department of Justice, accessed September 07, 2017.

25. Jon Guze, “Giving Credit where Credit Is Due,” John Locke Foundation, January 22, 2015.

26. Jon Guze, “More Good News About Civil Asset Forfeiture,” John Locke Foundation, January 28, 2015.

27. Jon Guze, “2015 In Review: Civil Asset Forfeiture Edition,” John Locke Foundation, February 2, 2016.

28. Jon Guze, “Missing Him (Justice Scalia) Already.” John Locke Foundation, March 30, 2016.

29. FAIR Act, S.642, 115th Cong.; Deterring Undue Enforcement by Protecting Rights of Citizens from Excessive Searches and Seizures Act of 2016, H.R. 5283, 114th Cong..

30. Jon Guze, “One Step Forward and One Step Back,” John Locke Foundation, July 27, 2017. Since this Spotlight was originally written, several members of the House have attempted to defund the equitable sharing program that Attorney General Sessions reinstated in July. See, Jon Guze “US House Attempts to Defund a Controversial Civil Asset Forfeiture Program,” John Locke Foundation, September 20, 2017. It remains to be seen whether this attempt will be successful.