This week I went to Kansas to speak with their Senate and House Commerce Committees about occupational licensing. I was joined by Lee McGrath of the Institute for Justice, which produced one of the essential reports on the effects of occupational licensing, “License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing.”

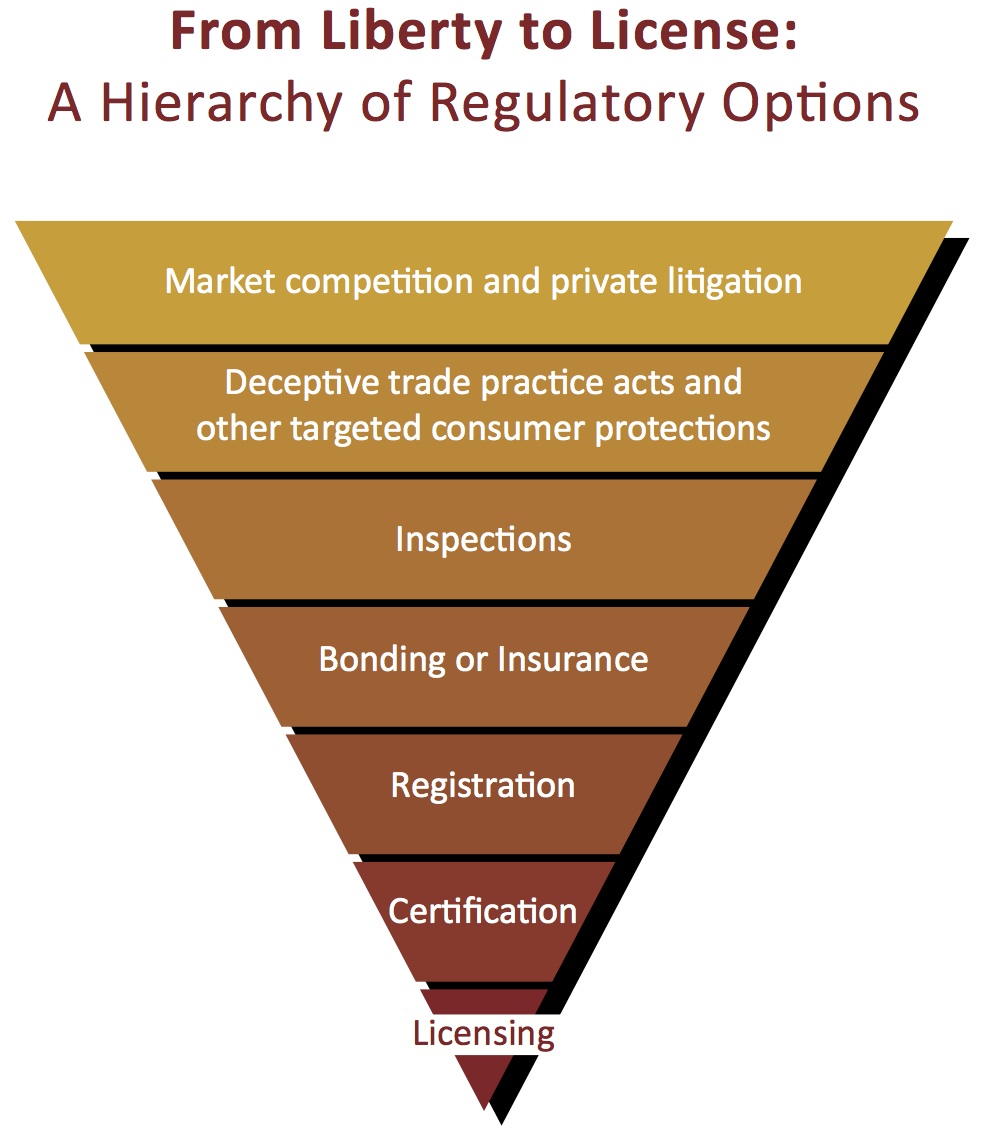

McGrath’s testimony included a discussion of how policymakers weren’t faced with a binary choice of either the very restrictive policy tool of licensing or nothing at all. (That would be quite the Hobson’s choice, wouldn’t it?) He explained that there is a wide range of options available to policymakers interested in responding to legitimate concerns but not interested in destroying occupational freedom in the process.

He used the following graph to illustrate that point. This graph appeared in IJ’s recent report “Boards Behaving Badly,” which drew lessons from last year’s Supreme Court decision in North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. FTC:

Source: Institute for Justice

Here is how McGrath defined the different levels (paraphrasing):

- Start at the top. The free movement of labor and market competition should be policymakers’default position. Before they leave that default position, they should identify an actual, serious market failure — one that is not addressed through litigation but that significantly threatens consumer health and safety.

- If legislators are concerned about protecting consumers from fraud, the proper regulatory response is to enhance the powers of the attorney general and the deceptive trade practices act.

- If the concern is over cleanliness, the proper regulatory response would be to require inspections.

- If the concern is over externalities, causing damage to third parties, then the proper regulatory response would be bonding.

- If the concern is over fly-by-night companies swooping in after, e.g., a natural disaster, the proper regulatory response would be registration with the Attorney General.

- If the concern is over asymmetrical information (sellers such as medical professionals or mechanics knowing more about their product than a consumer) or insurance reimbursement, the proper regulatory response would be certification.

McGrath found it extremely rare that policymakers would need new occupational licenses. Licensing offers scant evidence of marginal consumer protection over a competitive labor market, but it imposes significant costs to workers and consumers.

For those interested in learning more about occupational licensing, I invite you to read the following two John Locke Foundation reports:

- “Voluntary Certification: An economically robust, freedom-minded reform of occupational licensing,” Spotlight No. 46, April 9, 2015

- “Guild By Association: N.C.’s Aggressive Occupational Licensing Hurts Job Creation and Raises Consumer Costs,” Carolina Cronyism series, Spotlight No. 427, January 28, 2013

Click here for the Rights & Regulation Update archive.

You can unsubscribe to this and all future e-mails from the John Locke Foundation by clicking the “Manage Subscriptions” button at the top of this newsletter.