Walk into a commercial hair salon and you’ll find your stylist’s state license on the wall or the counter. It’s required to practice under the state’s regulatory framework to protect public health and safety. Whether licensing is necessary to ensure you get a good haircut is another story.

Back in the day, our neighbor cut hair for a lot of folks, just to be social and helpful. Other than the time she and my mom had to chop off my bangs to even them out after my unsuccessful attempt at a new style, the “non-professional” hair cuts were just fine. Nobody got hurt. And as the saying goes, it will grow back.

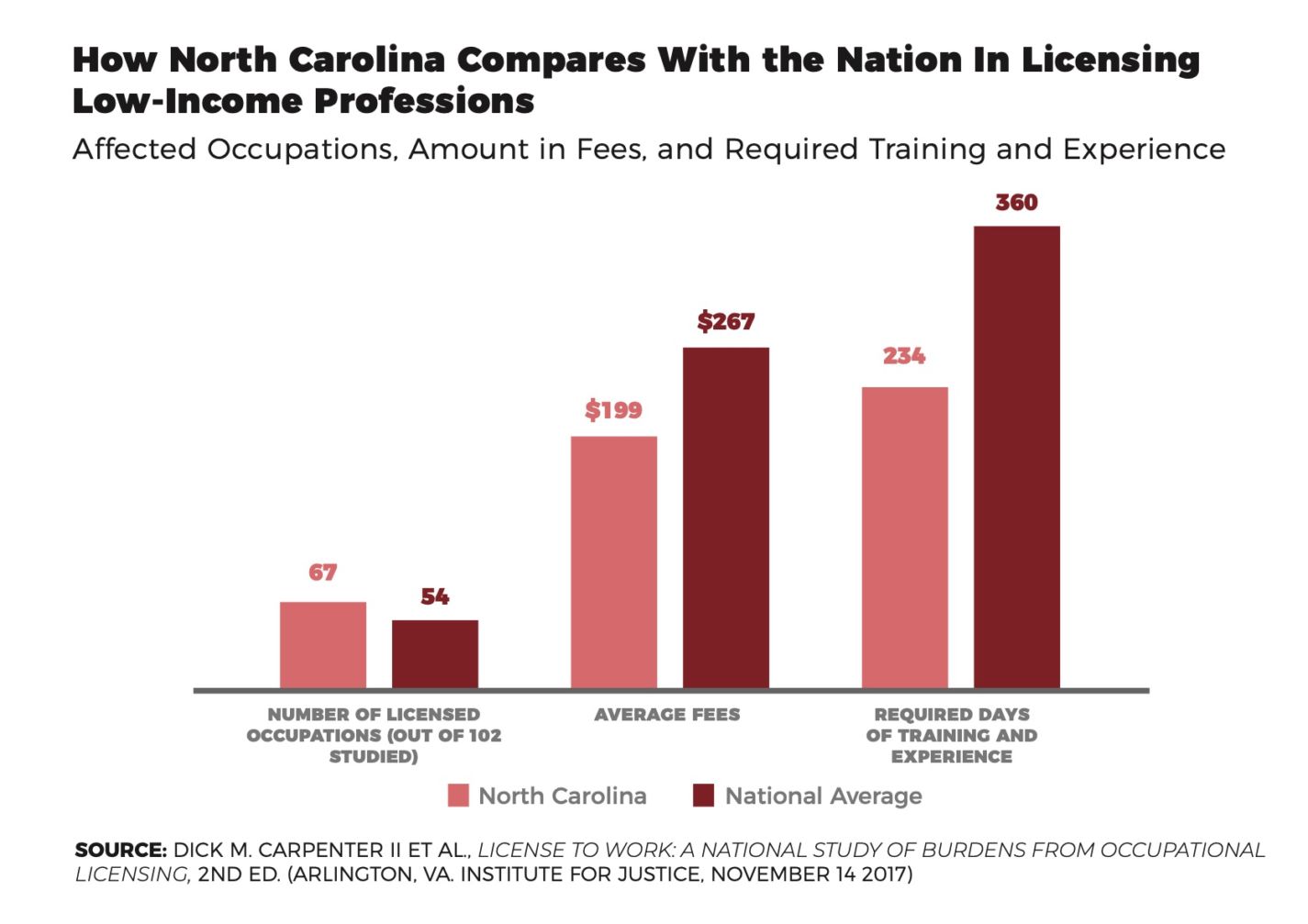

Turns out that North Carolina loves to license a lot of occupations under the broad umbrella of public health and safety.

But what do you do when a license really doesn’t make sense for the consumer, but serves primarily as a way for the state to have control? What do you do when the requirements set such a high bar that talented people are prevented from earning a living? That’s the case for hair braiders, as described by Daryl James and Jessica Poitras in this Carolina Journal column (emphasis is mine).

Mothers, aunts, grandmothers, sisters and friends have passed on their knowledge in this manner for centuries—without needing books or formal instruction. They are self-taught masters of their craft, but their training is not good enough for the North Carolina Board of Cosmetic Art Examiners.

Regulators require braiders to complete 300 hours in a state-approved program before earning income in their chosen occupation, no matter how much skill and experience they have. Tuition often tops $3,000, but the actual costs are higher due to lost wages while not working. Béké says the education requirement keeps braiders, who are mostly women, in an impoverished state.

The authors write that there’s a better way – a way of protecting the public while removing unnecessary barriers that keep people from putting their skills to work for themselves and their families.

Government has an obligation to protect public health and safety, which is why North Carolina regulates the beauty industry. But unlike cosmetology, braiding does not involve harsh chemicals, heat or irreversible processes. Even in worst-case scenarios, consumer risks are low.

A better model for oversight already exists in the restaurant industry, which is more closely tied to public health and safety than braiding. Culinary schools offer training for aspiring chefs, but most states do not require culinary professionals to take tests or become licensed.

Reforming the licensing regime means fewer barriers. More opportunity. More self-sufficiency. More prosperity.

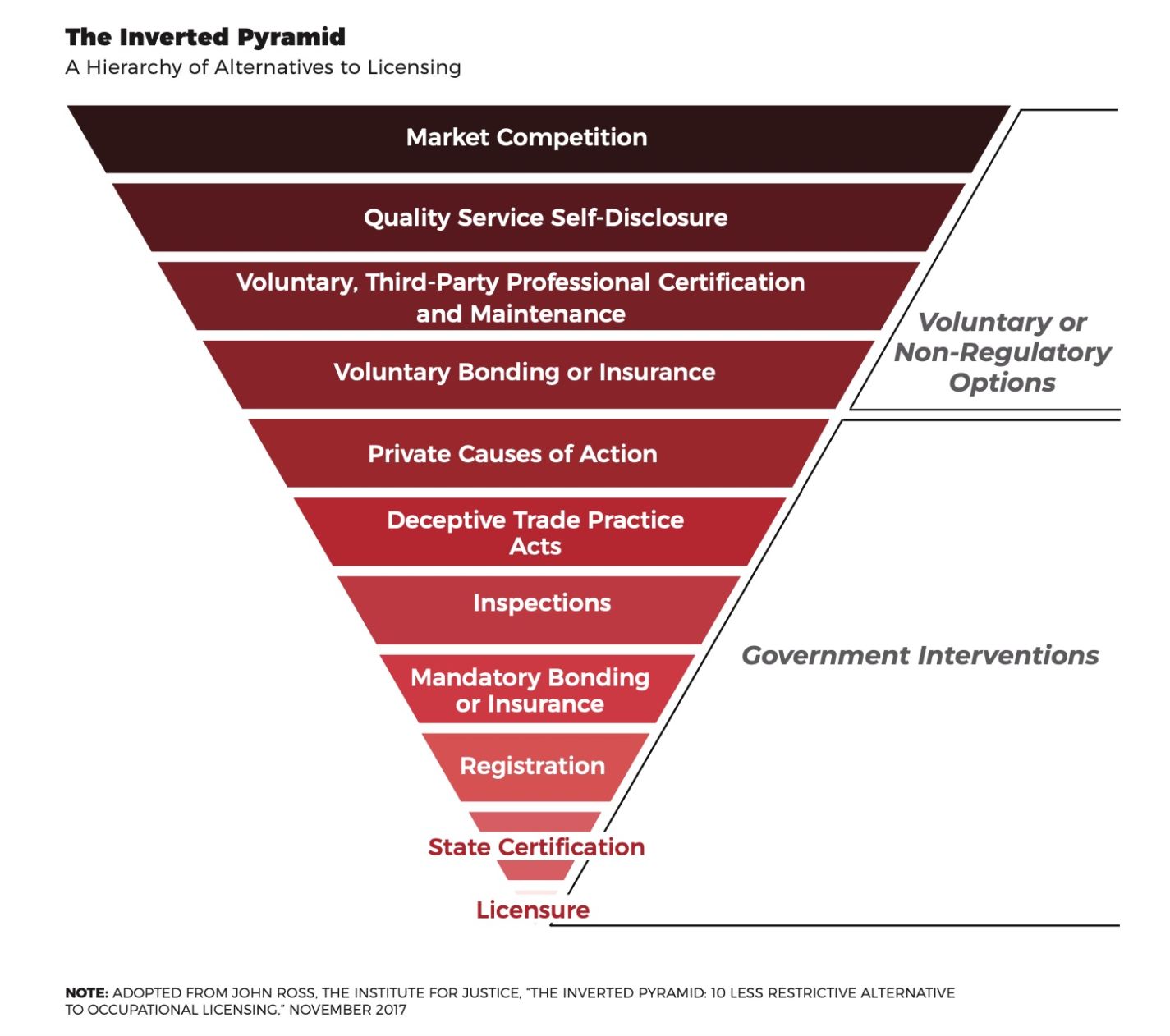

To get there, the Locke Foundation advocates for reform that favors the least restrictive approach as first choice. Licensing, as you see below, should be the last choice. The plight of hair braiders tells you why.