John Hood wrote this week about the instructive philosophy of Cicero. Wait, don’t go yet.

Cicero wasn’t just the “Roman orator and statesman … contemporary (and enemy) of Julius Caesar … hero to the founders of North Carolina and the United States as a whole.” He was also the originator of North Carolina’s state motto, To Be Rather Than to Seem (Esse Quam Videri).

And he wrote it in a piece about friendship!

This principle extends well beyond relating with friends, of course. It was chosen in 1893 as our state motto.

The North Carolina History Project puts that motto in its context. Cicero’s sentence containing it read “Virtute enim ipsa non tam multi praediti esse quam videri volunt.” I like the translation from University of Michigan Latin Professor Frank Copely:

[N]ot nearly so many people want actually to be possessed of virtue as want to appear to be possessed of it.

Wisdom in policymaking

I have long urged that our policymakers apply the principle of being rather than seeming to their policies. George Leef called it a “crucial distinction” for policymakers — distinguishing “between actually helping the poor and what politicians usually do, which is spending money or enacting laws that are supposed to make it look as if they’re helping the poor.”

I recently praised a Maryland county leader who sought being over seeming when the issue was whether to hike the minimum wage. That is an issue where the impulse to seem compassionate causes more harm than good.

Isiah Leggett (D), the county executive of Montgomery County, resisted the urge to take the easy position of seeming to adopt a policy to help poor workers. Smartly, he asked for a study to see if the policy would actually help them. The study came back, and Leggett’s wisdom may have preserved tens of thousands of jobs.

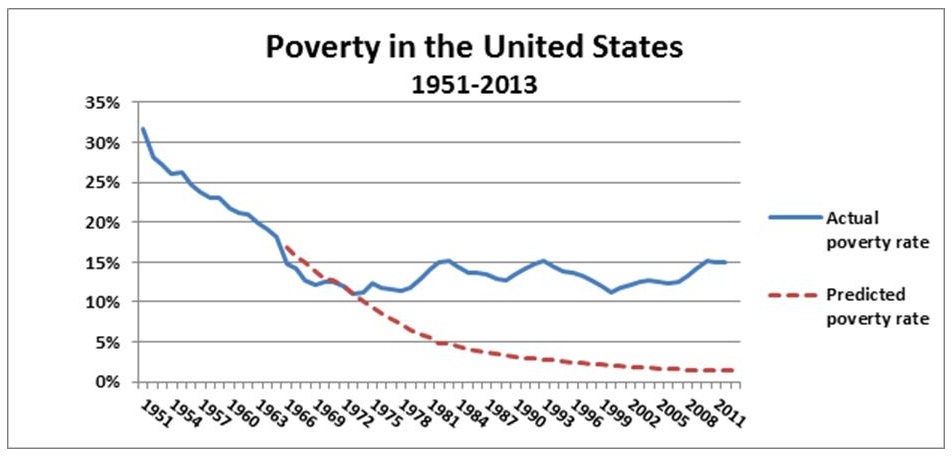

Here is a chart from that issue showing the dismaying lack of effect of the trillion-dollars-per-year “War on Poverty,” especially compared with how the poverty rate was steadily falling on its own before the government intervened:

Overt, highly visible government interventions on behalf of the poor certainly seem to be essential policies. But negative unintended consequences, faulty assumptions, and perverse incentives show that the policies have not been effective at all.

Cato’s David Boaz recently highlighted how a bunch of government policies intended to help people and make us safer have instead left them stranded in poor areas with dwindling jobs and wealth.

America was once a land of economic mobility, where people could “strike out for greener pastures,” chase their dreams with “vagabond shoes longing to stray” and leave their “little town blues … melting away” — not so much now. Why?

Government aid programs and low-income public housing provide powerful disincentives to leave, even to go where jobs are. Overall growth in occupational licensing, combined with broad differences in states’ licenses, come together to make moving a tougher choice. And cities’ highly restrictive land-use regulations jack up home prices beyond the reach of poor people from small towns.

This decade we have seen North Carolina leaders adopting empirically tested policies (i.e., being) on taxes, spending, and regulation. North Carolina’s turnaround has made the state a national model for growth the right way.

But we have also witnessed the growth of a movement whose basis is proclaiming that the ad hoc opposition to those policies and others is “moral” (seeming).

Ensuring the virtue is actually possessed

Cicero’s maxim wouldn’t be so compelling if it wasn’t ultimately so difficult to uphold. Results are hard to obtain, and some are content with the facile.

In consequence, the intent to do good grows to greater importance than actual results. Michael Knox Beran’s review of William Voegeli’s The Pity Party highlighted this aspect:

A “defining characteristic” of this politics, Voegeli writes, “is a strong preference for political stances that demonstrate one’s heart is in the right place, combined with a relative indifference to whether the policies based on those stances, as actually implemented, do or even can achieve their intended results.”

In other words, the politics of kindness is another pretty flower in the modern epicure’s garden of earthly delights. Such a politics is agreeable to behold; its aroma is pleasant.

That it is also, in certain cases, toxic to those whom it is intended to help is beside the point, for its purpose is not to lift up the struggling poor man, but to soothe the conscience of the anxious rich man. It is the hypocritical engine of the higher narcissism.

This regrettable politics has turned what should be self-evident — doing something to help the poor should, at the very least, actually help the poor — sound like a radical statement.

So be it. The word radical has its root in a word Cicero would have used for root, radix. Let’s get radical:

- Policies put forth to help the poor should actually work to help the poor.

It doesn’t matter whether helping the poor was the original intent or that failing to help or making things materially worse on net is a negative unintended consequence.

- If those policies fail, they should be repealed.

Being vs. seeming even applies to intentions. Truly good intentions would not be satisfied with a one-time demonstration of their existence and show no interest beyond that. The results would ultimately matter most.

- Practices and systems that help the poor should be encouraged.

Policy is a small part of the overall social equation. Private acts and social systems can be beneficial to the poor and mitigate harms. It doesn’t matter whether helping the poor is a deliberate intent or a positive unintended consequence. The root of the study of economics is how people looking after their own interests somehow wind up serving other people’s interests, too — coordinating goods and services among themselves so that society grows and flourishes. The mystery of free enterprise is, it invariably happens in ways unachievable by central planners even with the greatest and purest of intentions.

- Practices and systems that help the poor must certainly not be thwarted or discouraged.

Especially not by government policies trying to do at a public cost what people are effectively providing all on their own, or by purists who object to beneficial results happening despite a lack of identifiable good intentions.

The radix of that radicalism is championing things shown to be beneficial.