One goal when drawing congressional districts is to keep political communities, including counties, together. As Jim Stirling and I noted in our report, Limiting Gerrymandering in North Carolina, “[W]hile there is no constitutional limit on how many counties can be traversed on a congressional map, a 13-county limit for the 14-district congressional map is reasonable.”

At first glance, the congressional map the General Assembly drew in 2021 appears to meet that criteria. It only split 11 counties. However, it only achieved that by splitting three counties twice, meaning that the map had a total of 14 county splits, one more than necessary.

(That map was not used in an election. A court-ordered map was used in the 2022 election instead.)

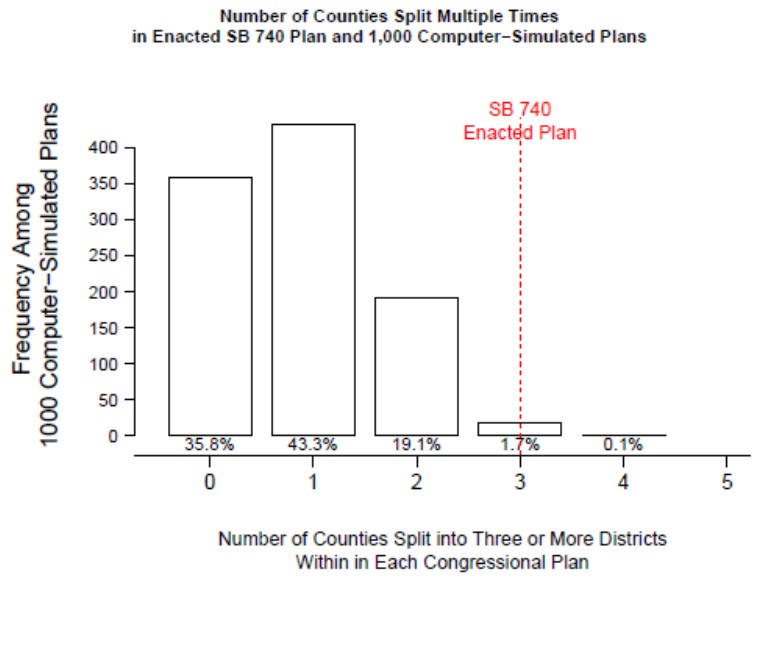

Political scientist Dr. Jowei Chen studied the probability of counties being “split into three or more districts” as part of his expert testimony in the Haper v. Hall redistricting lawsuit. The results are in Figure 1.

Chen found that at least one county was split three or more times nearly two-thirds of the time in the 1,000 computer-generated maps drawn using the criteria the General Assembly adopted in 2021. The most common outcome was for one county to be split multiple times (43.3%) followed by zero counties with multiple splits (35.8%) and then two counties with multiple splits (19.1%). Only 1.8% of the time were three or more counties split multiple times.

So, having three counties split three ways is unexpected. Is it justified? Let’s look at each case.

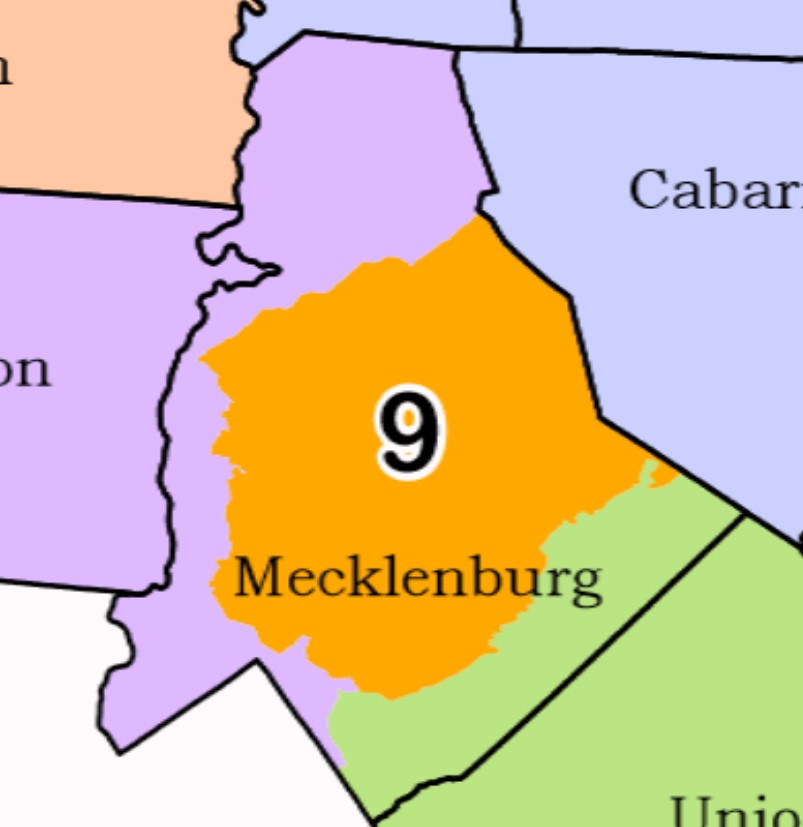

The Righteous Three-way Split: Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg County has to be cracked. Its 2020 Census population of 1,115,482 is much larger than the required congressional district population of 745,670 or 745,671. Charlotte has a census population of 874,579, meaning that at least part of North Carolina’s largest city will have to be split off from the rest.

That creates a dilemma for map-makers. I noted that dilemma in October of 2021. So, rather than repeat myself, I will copy myself:

Map-drawers can keep Charlotte together to the maximum extent possible, but doing so would require that they split Mecklenburg County three ways, with the northern suburbs joining other suburbs in counties west of Charlotte in the 10th District. Mint Hill and Matthews would join the 9th District along with the portion of Charlotte that is already in the 9th….

[A] three-way division of Mecklenburg County is more consistent with the redistricting criteria adopted by the General Assembly for considering municipal boundaries since it divides Charlotte less than a two-way division would. It would also be consistent with preserving communities of interest: who has a stronger community of interest claim for being in a district with central Charlotte, someone living in the town of Cornelius in northern Mecklenburg County, or someone living in southwestern Charlotte?

In short, splitting Mecklenburg three ways is not the only way to deal with the dilemma of how to draw congressional districts there, but it is a perfectly valid way and preferable to the other options available.

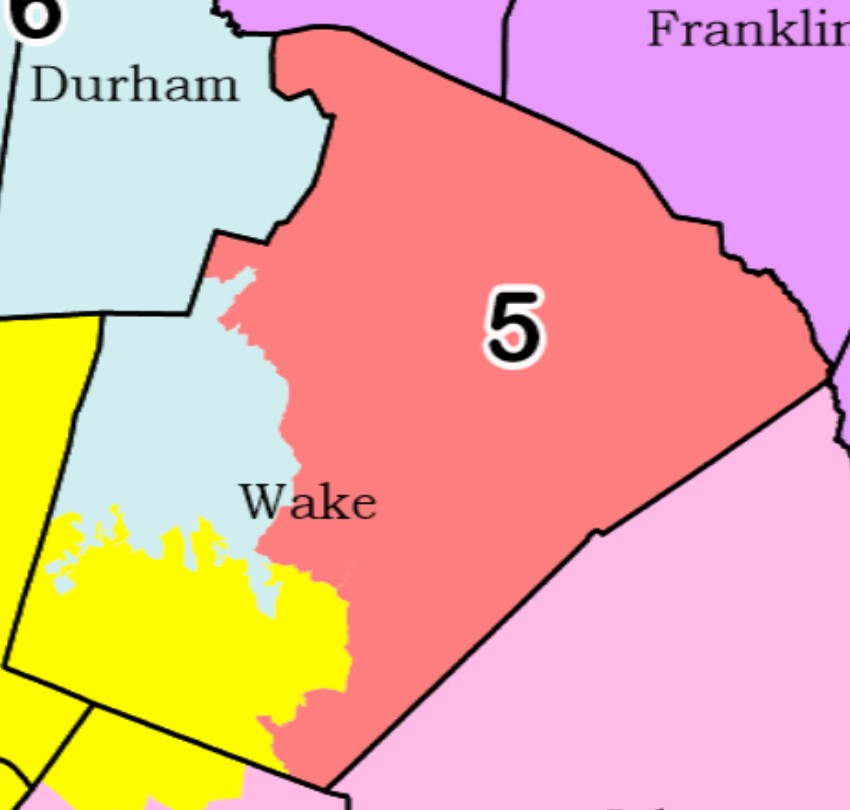

The “Meh” Three-way Split: Wake

Like Mecklenburg, Wake County has a larger population (1,129,410) than that of a congressional district. That means the county must be split and least once. However, Raleigh, Wake County’s largest city, only has a population of 466,106. So, all of the city can comfortably fit within a congressional district. The questions, then, are what other parts of the do you add to Raleigh to form a district and what do you do with the rest of the county?

Unlike with Mecklenburg, there is not a strong positive argument for splitting Wake County three ways. However, Wake’s geography and population make it a practical option.

Legislators put Raleigh with suburban areas in the northern and eastern parts of the county in one district. They then put the inner suburban municipalities of Cary (itself the 7th largest city in North Carolina) and Apex in with Durham and Orange counties. Finally, they put the outer suburbs of Holly Springs and Fuquay-Varina in a district with suburban and rural areas to the west (the 7th District). Those are all natural communities of interest from the perspective of Wake County residents.

There is a problem with the 7th District, however, which we will explore in the next section.

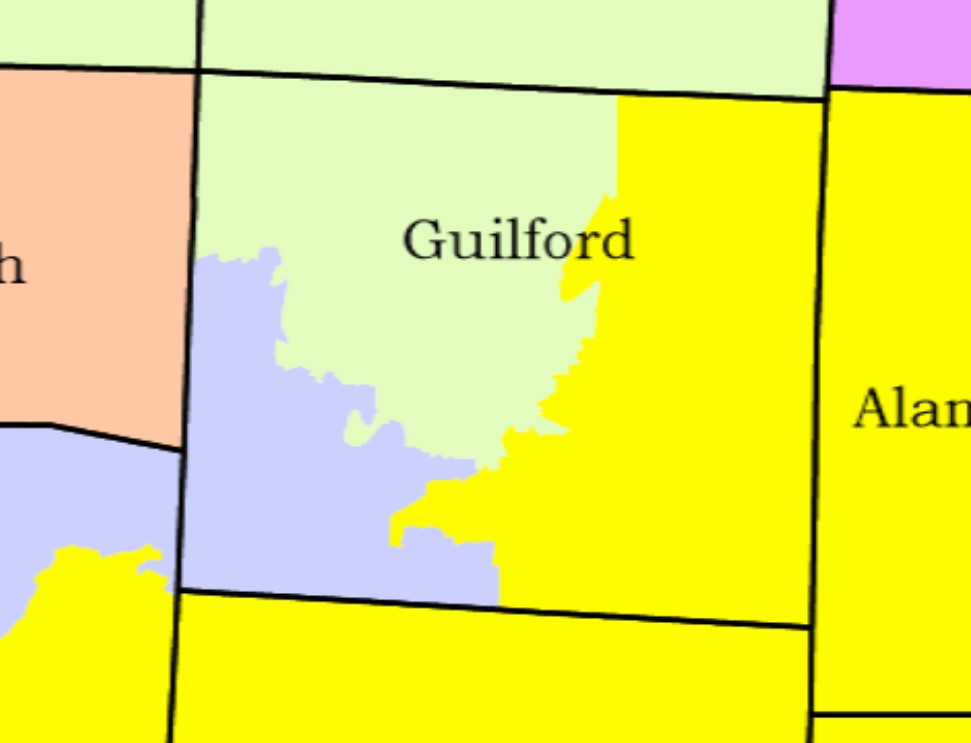

The Gratuitous Three-way Split: Guilford

The 7th District runs west from southern Wake County and is part of the last three-way split, this time in Guilford County. Guildford’s 2020 census population is 541,299 so the whole county can comfortably fit as part of a congressional district.

As seen in the state congressional district map, part of the reason for Guildford’s three-way split is partially the result of legislators running the 10th, 11th, and 12th districts parallel to each other before terminating them in the Triad. The 11th ends in Forsyth County while the 10th and 12th wrap around the 11th to join the 7th District in dividing Guildford.

The only bright spot in Guilford is that Greensboro is kept largely intact in the 11th.

The shape of those districts was drawn at least in part by a desire to prevent the homes of Republican incumbents from being put in the same districts. (Members of Congress are not required to live in the districts they represent but they have a strong preference to do so.)

Legislators complicated things further by drawing a new district west of Charlotte in an apparent bid to give House Speaker Tim Moore a shot at Congress, a shot he declined to take. Creating that district forced the 10th, 11th, and 12th districts to snake eastward.

Finally, it is probably not an accident that the map splits the biggest concentration of Democratic voters in the Triad region into three Republican-leaning districts, helping Republicans secure a map that favored them in 10 of the state’s 14 districts.

Not All County Splits Are the Same

So, what have we learned from all this?

First splitting counties is necessary when drawing districts and splitting at least one county multiple times is normal. However, splitting three or more counties multiple times in a single map is a sign that legislators did not use traditional redistricting criteria (such as compactness and keeping political subdivisions whole) in drawing that map.

Finally, not all three-way county splits are created equal. One of those splits in the map approved by the General Assembly in 2021 is a reasonable fix to a redistricting dilemma, another not neither good nor bad, and the third does not appear justifiable under traditional redistricting criteria.

As state legislators have a go at passing a third congressional map in as many years, they should keep county splits, especially multiple splits, to a minimum.