The North Carolina Supreme court is scheduled to rehear two high-stakes election lawsuits on redistricting and voter ID. The State Supreme Court ruled on two different voter ID lawsuits last year: one regarding the constitutional amendment and the other regarding the law implementing voter ID passed by the state legislature. The court is only looking to rehear the case regarding the implementation law.

While many left-wing actors, including Governor Cooper, have criticized the rehearings as stepping outside the judiciary’s role, rehearing a case has precedents.

Petitions to rehear are rarely used, but the court allows a request to rehear under rule 31 of North Carolina Rules of Appellate Procedures. The qualifications are strict; the petition needs to be filed within fifteen days since the ruling was mandated and illustrate where the court may have errored in its decision in facts or law.

The outgoing 4-3 Democratic majority expedited both cases late last year and ruled against legislative defendants just before the court moved to a 5-2 Republican majority. Democrats justified this uncommon tactic on the NC Supreme Court by citing “the need to reach a final resolution on the merits at the earliest possible opportunity.” The problem with that argument is that these cases have no immediate impact. Legislative and congressional maps, alongside voter ID, had already been settled for the 2022 election year; the earliest either ruling could have an effect would not be until 2024. There was no legal justification for expediting the cases.

While this alone justifies the court rehearing the cases, there are even more significant reasons why the court should have a second look at these rulings.

The prior Supreme Court’s decision to throw out the voter ID case hinges almost entirely on past cases against the North Carolina General Assembly. Instead of looking at the language of the law, the court assumed the legislators’ intent and placed the burden of proof on the state as the defendant in the case.

The voter ID law that the general assembly passed in 2018 is comprehensive and allows for various forms of ID, ranging from driver’s licenses, state IDs, tribal IDs, to even student IDs from universities and community colleges. It also allows for religious objections, an exception to presenting an ID if the voter has “reasonable impediments, and the option to receive a provisional ballot should a voter fail to have any accepted form of ID on them. The court failed to consider these factors and wrongfully tried to create a narrative based on prior court rulings rather than the evidence before them.

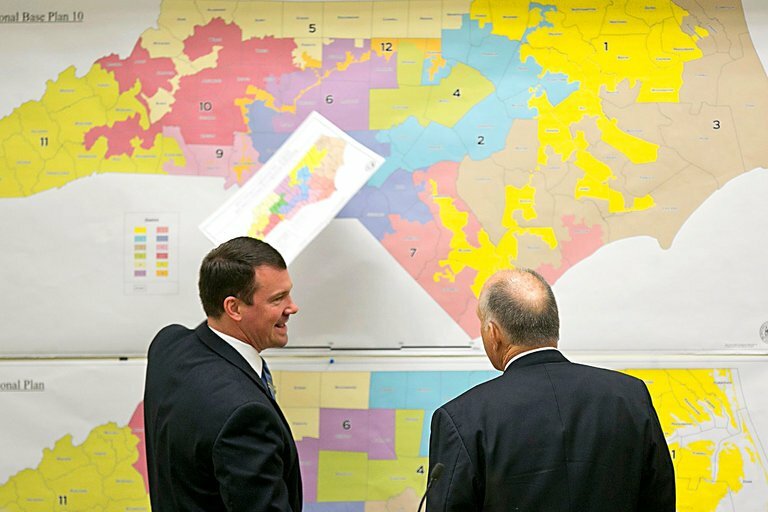

When it comes to redistricting, the issue comes from the court’s lack of clarity in what is and is not a partisan gerrymander. In a ruling that can best be described as the legal equivalent of bring me a rock,” the court gave vague qualifications and standards for determining a partisan gerrymander that effectively turned the State Supreme Court into a required body for all redistricting. With only vague standards by which to judge the maps, the prior Supreme Court ruling made it impossible for anyone, including court-appointed map drawers, to understand how to create compliant maps. This lack of standardization in the ruling meant the maps were judged under multiple criteria and ultimately subject to no consistent standard.

The redistricting and voter ID cases were subject to numerous breaks in precedent in 2022. After winning in Wake County trial courts, plaintiffs, not the defendants, were the ones to file these appeals directly to the Supreme court, bypassing the Republican majority Court of Appeals.

While it is rare for cases to be reheard, it is justifiable considering how the prior court handled them. Not only were both these cases fast-tracked through the courts before Democrats lost a majority, but they also broke from court precedents in numerous ways. These decisions by the outgoing Supreme Court seemed to come more from a political objective than a judicial philosophy.