- With the next scheduled round of redistricting eight years away, now is the best time to talk about redistricting reform

- Following traditional redistricting criteria more strictly and making the “Stephenson process” a permanent part of the state constitution can limit gerrymandering

- Another tool to limit gerrymandering is banning the use of political and racial data and not considering incumbents’ home addresses when redistricting

The General Assembly enacted new state legislative and congressional maps on October 25. It is the third set of legislative maps and the fourth congressional map North Carolina has had over the past four years.

So, North Carolina’s latest round of redistricting is behind us, other than the inevitable lawsuits. As painful as it may sound, now is the best time to consider redistricting reform. Many of those reforms can be found in a June 2023 report I wrote with Jim Stirling, “Limiting Gerrymandering in North Carolina.”

Why Talk About Redistricting Reform Now?

The allure of redistricting reform for Democrats is obvious: it is a way for them to achieve a bigger share of power.

They enjoyed over a century of almost uninterrupted power in the General Assembly following their defeat of Republican and Populist Party candidates in 1898. It ended in 2010 when Republicans swept to power in the General Assembly, just in time to control the once-per-decade regular redistricting process in 2011. With Republicans still firmly in control of the General Assembly, anything that lessens the power of legislators to draw maps as they see fit can only help Democrats.

The political case for Republicans supporting redistricting reform is not so clear at first. Why would they voluntarily give up the power to gerrymander that Democrats used against them for over a century?

Democrats created Vance County in 1881 to concentrate Black Republican voters in one county, making the surrounding counties more Democratic in General Assembly races. UNC-Chapel Hill history professor Harry Watson said, “This is the only case that I’m aware of where they created a permanent county for the purposes of changing election results.”

Republicans should remember that they prevailed in 2010 in maps Democrats had drawn for their own maximum benefit. The Democrat’s problem, when they drew those maps, was that they had declining support coupled with too many incumbents to protect.

While there is no evidence that Republicans are currently suffering a decline in support like what Democrats faced when they last drew maps two decades ago, the GOP has many incumbents to protect and shifting patterns of partisan support to consider. If Democrats can increase their support in suburban areas over the next seven years and 2030 turns out to be a “blue wave” election, Republicans could find themselves out of power just in time for the next round of redistricting.

That uncertainty could make Republicans more receptive to adopting redistricting reforms in the General Assembly’s 2024 short session.

Centering Communities

Redistricting should be about drawing districts that serve communities, not political calculations, and redistricting rules should reflect that.

The first way to accomplish that is to respect the whole county provision in the North Carolina State Constitution when drawing state legislative districts. When balanced with equal population requirements, that provision minimizes how often legislators can split counties in legislative maps.

It has been done over the past two decades by adhering to the so-called Stephenson process established by the North Carolina Supreme Court in 2002 in Stephenson v. Bartlett. The process minimizes county splits and predetermines how some counties are grouped to form districts, limiting how creative legislators can be when drawing those districts.

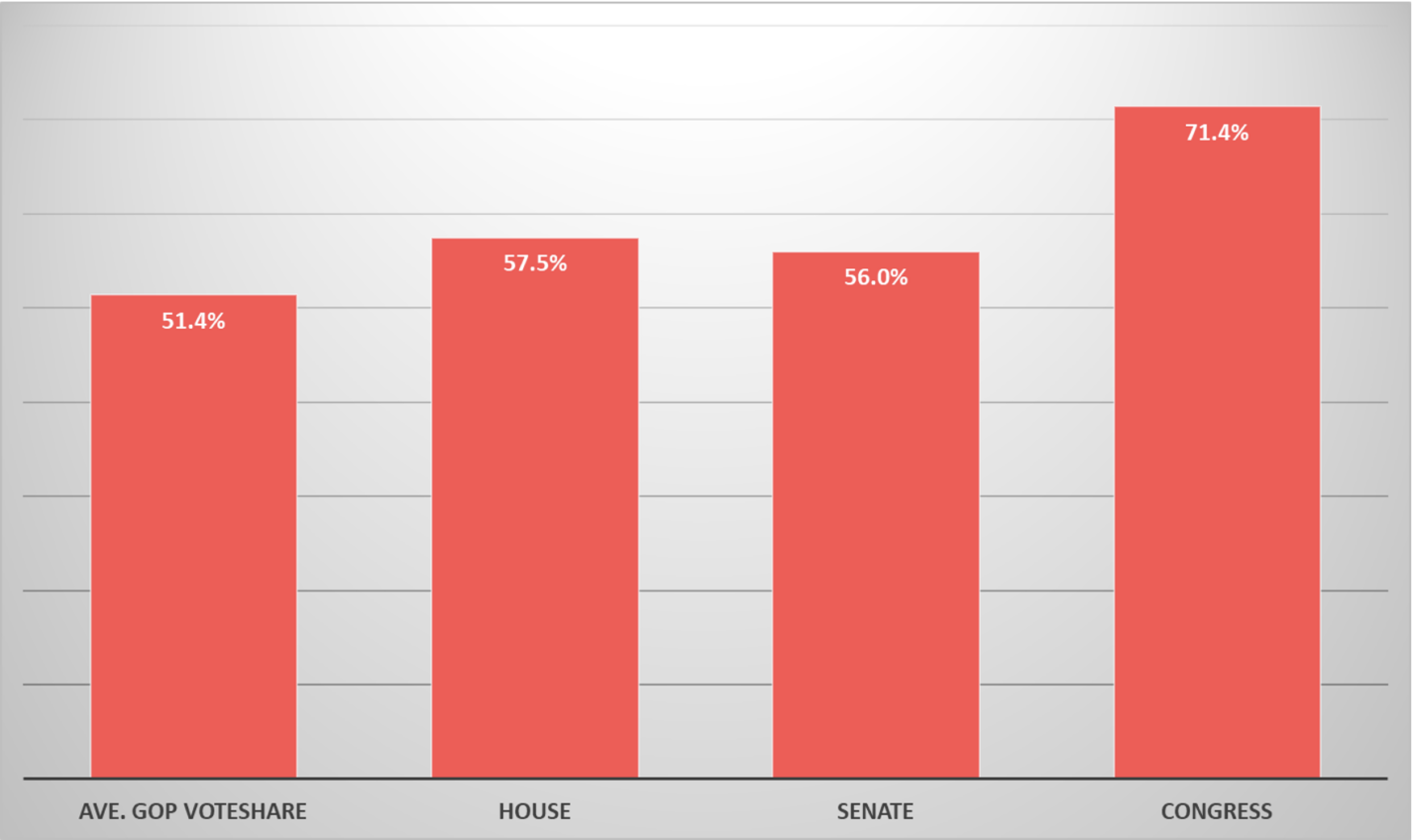

The impact of the Stephenson process can be seen by comparing the share of seats Republicans are expected to win in North Carolina’s races for state legislature and Congress in 2024 (see chart below). North Carolina leans slightly in favor of Republicans, with that party having an average vote share of 51.4 percent of Council of State and statewide judicial races. The GOP is expected to win slightly under 60 percent of seats in the General Assembly, with much of the variance from vote share explained by political geography and the tendency for majority parties to be overrepresented in legislatures.

By comparison, Republicans are expected to win 71.4 percent of North Carolina’s congressional seats in 2024. There is no Stephenson process for congressional districts.

Average Republican vote share in 2020 Council of State and 2022 statewide judicial races compared with expected Republican share of North Carolina General Assembly and congressional seats after the 2024 election.

The Stephenson process should be permanently enshrined in the North Carolina Constitution to cement protection of communities during redistricting.

While it is not practicable to apply the Stephenson process to congressional races, further regulations can be imposed on congressional and state legislative maps to center communities in the redistricting process. Those include minimizing precinct splits (no more than 13 for the congressional map), avoiding municipal splits within counties where possible, and requiring districts to be as compact as practical. Most are already part of the redistricting process but not followed as strictly as the Stephenson process.

Limiting What Data Can Be Used When Redistricting

In addition to centering communities, North Carolina can limit gerrymandering by restricting what data can be used when drawing maps.

Head counts are the only data the General Assembly should use when drawing districts. The use of political data, such as party registration numbers or the partisan voting tendencies of precincts, should be banned. Banning those data alone would not prevent gerrymandering; legislators and others involved in the redistricting process already know the partisan preferences of communities. They can also review partisan data before starting the map-drawing process.

Those facts don’t make banning political data useless, however. Excluding those data during map drawing makes gerrymandering less precise, limiting its effectiveness. A ban on political data was part of the redistricting process in 2021, but it was abandoned during the court-ordered round of redistricting in October.

Racial data should also be banned when drawing maps. Despite claims to the contrary, there is no need to use racial data in order to draw maps that comply with the Voting Rights Act. Adhering to the traditional redistricting criteria noted in the previous section is sufficient for drawing VRA-compliant maps. In addition, using racial data would make those drawing maps vulnerable to legal claims that race was the predominant factor in drawing some districts, a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Another factor considered during redistricting is the home addresses of incumbents. The North Carolina Constitution requires state representatives and senators to live in their districts. As populations shift, however, trying to keep those incumbents in their districts leads to abandoning traditional redistricting criteria and creating distorted districts. While there may be some justification for maintaining legislators’ relationships with their constituents, it should not come at the expense of traditional criteria such as compactness and keeping political communities whole.

Traditional Criteria and Data Bans Are Sufficient Protections

Other reforms, such as mandating transparency in the process and having maps initially drawn by an advisory redistricting commission, could further help reduce gerrymandering. As we detailed in our “Limiting Gerrymandering” report, however, centering communities and banning some data would help reduce gerrymandering in North Carolina without the need for additional changes to the process. The time to implement those reforms is now, while the 2030 elections are still far off, and the results of those elections are more uncertain.