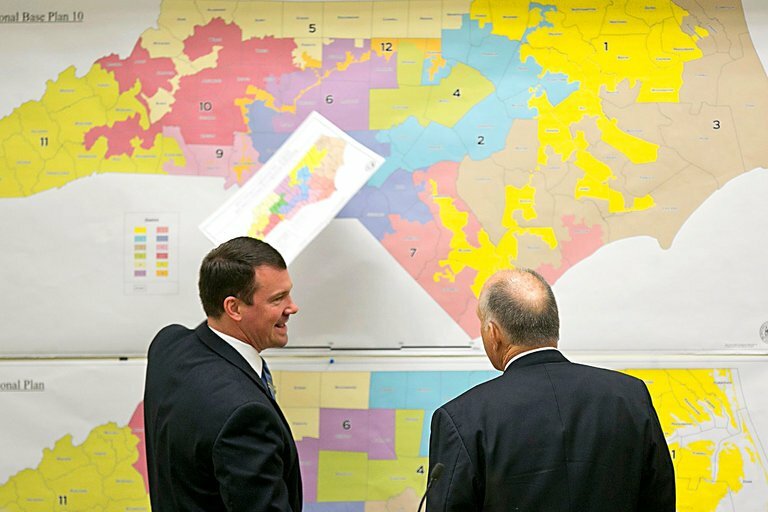

A case out of South Carolina could help set limits on claims of racial gerrymandering, further clarifying how such claims may affect districts the North Carolina General Assembly will draw later this month.

Alabama Case’s Limited Impact

I noted in June how a racial gerrymandering case from Alabama, Allen v. Milligan, would likely have little impact on redistricting in North Carolina:

We should therefore expect that Allen v. Milligan will have little to no impact on North Carolina’s congressional districts when the General Assembly redraws them later this year. The only possible exception is Rep. Don Davis’ 1st Congressional District in the northeastern part of the state. The Cook Political Report changed its rating for the district from toss-up to lean Democratic in anticipation of the General Assembly keeping more Black voters in his district.

Like much of rural North Carolina, however, Davis’ district is trending to the right and will likely lean Republican by the decade’s end. The only way to avert that trend would be to add urban Durham County to the district, but doing so would involve ignoring traditional districting principles, the very behavior that caused the Supreme Court to overturn North Carolina’s congressional map in Shaw v. Reno.

The factors leading up to that “therefore” include a relative lack of racially polarized voting by Whites in North Carolina and the state’s political geography allowing legislators to draw enough VRA-compliant districts without using racial data to draw districts based on race intentionally.

South Carolina: Partisan, not Racial, Gerrymandering

The United States Supreme Court heard another racial gerrymandering claim on October 11. They will not issue a ruling for several months, too late to affect the General Assembly map drawing later this month. But it could influence the course of the inevitable lawsuits that come after those maps are drawn.

The case is Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP. The heart of the case is the question of whether a partisan gerrymander is also automatically a racial gerrymander in a state with a substantial Black population.

Several justices also pointed out that plaintiffs failed to provide an alternative map that would accomplish the defendants’ goals of maximizing the number of Republicans in the state’s congressional delegation. The Supreme Court determined in a 2019 case from North Carolina, Rucho v. Common Cause, that political gerrymandering is a nonjusticiable political question and therefore outside of the court’s purview.

Chief Justice John Roberts seemed exacerbated by the plaintiffs’ lack of direct evidence of a racial gerrymander:

“We’ve never had a case where there has been no direct evidence, no map, no strangely configured districts,” said Chief Justice John Roberts. “Instead, it [is] all resting on circumstantial evidence.” Roberts said that it wasn’t impossible to bring a racial gerrymander claim on circumstantial evidence, but “this would be breaking new ground in our voting rights jurisprudence.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh seemed convinced that the state likely relied on political, rather than racial, data to draw the congressional map:

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, on the other hand, seemed to have little trouble with the state’s explanations for how the map ended up as it did. Kavanaugh asked what the court should do if it finds the state relied on solid political, rather than racial, data to draw the district.

“If that data is good, should we reverse?” he asked.

Roberts’ and Kavanaugh’s views are important because they joined the three progressive justices on the court to overturn Alabama’s congressional map as a racial gerrymander in Milligan. With both openly skeptical of the plaintiffs’ claims in this case, it appears likely that using racial gerrymandering claims as an alternative route to strike down political gerrymanders will be a legal dead end.

What Would a Reversal in the South Carolina Case Mean?

If the Supreme Court overturns the lower court ruling in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP and upholds that state’s maps, it will eliminate a potential route for a racial gerrymandering claim against North Carolina’s new congressional and state legislative maps.

In one sense, such a ruling would reinforce the lesson from the Alabama case: as long as the North Carolina General Assembly follows traditional redistricting criteria and does not use racial data, its maps should be safe from lawsuits claiming racial gerrymandering.