- While states consider enormously expensive plans to rework their entire electricity systems to cut CO2 emissions, energy-based emissions are still increasing across most of the world, especially China

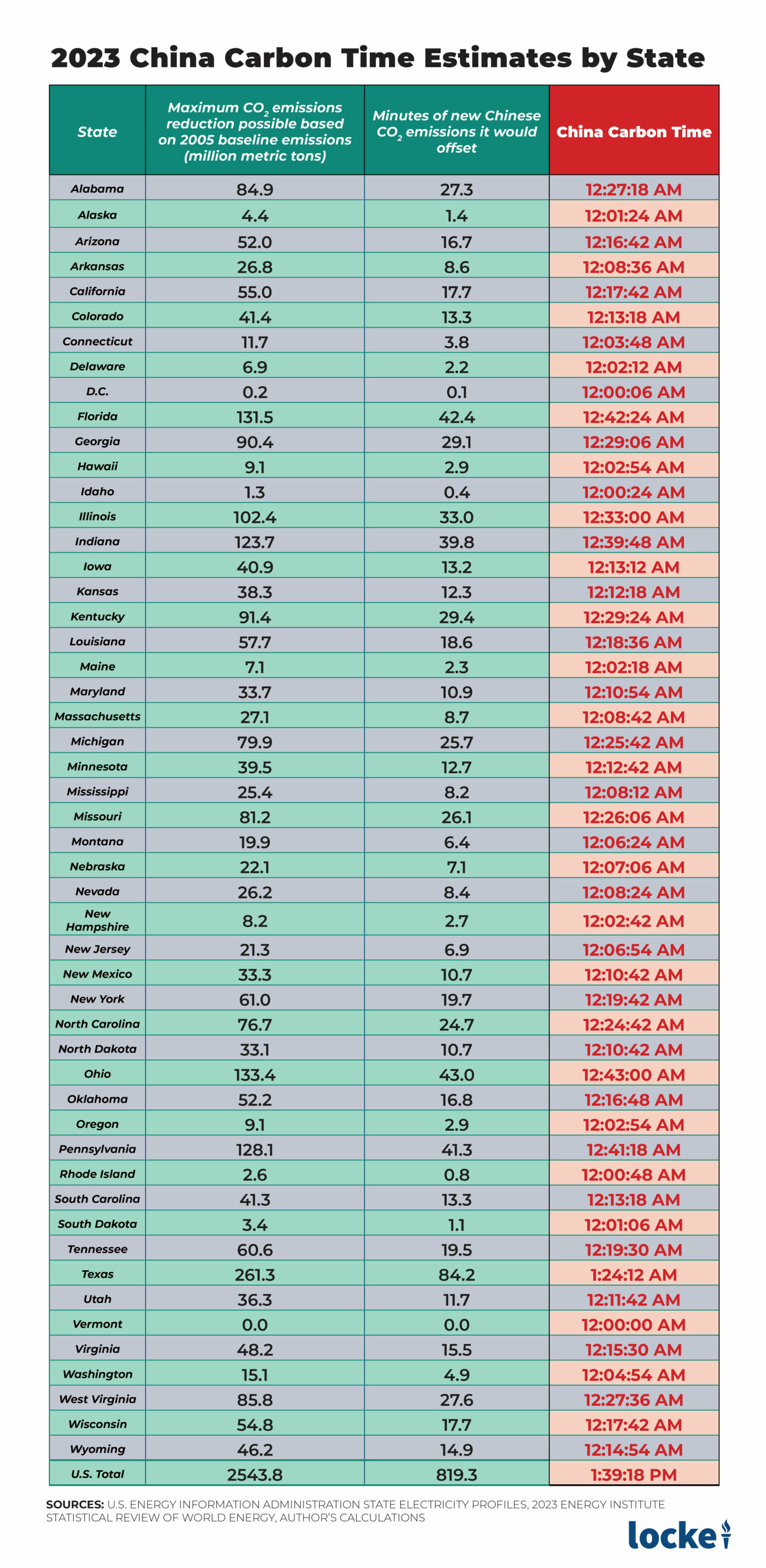

- China Carbon Time shows, state by state, that the maximum emissions each state could cut would still not reduce global emissions — it could only offset a tiny and dwindling bit of China’s increase

- State policies forcing CO2 reductions are all cost, no conceivable benefits to their citizens

How much would it cost your state to “decarbonize” electricity? That is, how much would it cost people in their roles as ratepayers and taxpayers to eliminate all carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from electricity generation in your state?

For example, North Carolina has a Carbon Plan with early cost estimates ranging from $141.7 billion and $162.3 billion. By the late 2020s, the North Carolina Utilities Commission’s Public Staff has estimated that North Carolina’s power bills will be double what they are now.

Huge costs, but they must be weighed against their benefits. Would these big expenses and upheavals in electricity rates and reliability be worth it? Despite higher power bills, less reliability, and more rolling blackouts, could we at least see global CO2 emissions falling — which we’re told would mean fewer bad weather events?

What if all that sacrifice would really only buy a tiny offset of the enormous increase in energy-based CO2 emissions coming from China? That’s what China Carbon Time shows.

When reducing CO2 emissions doesn’t reduce global emissions

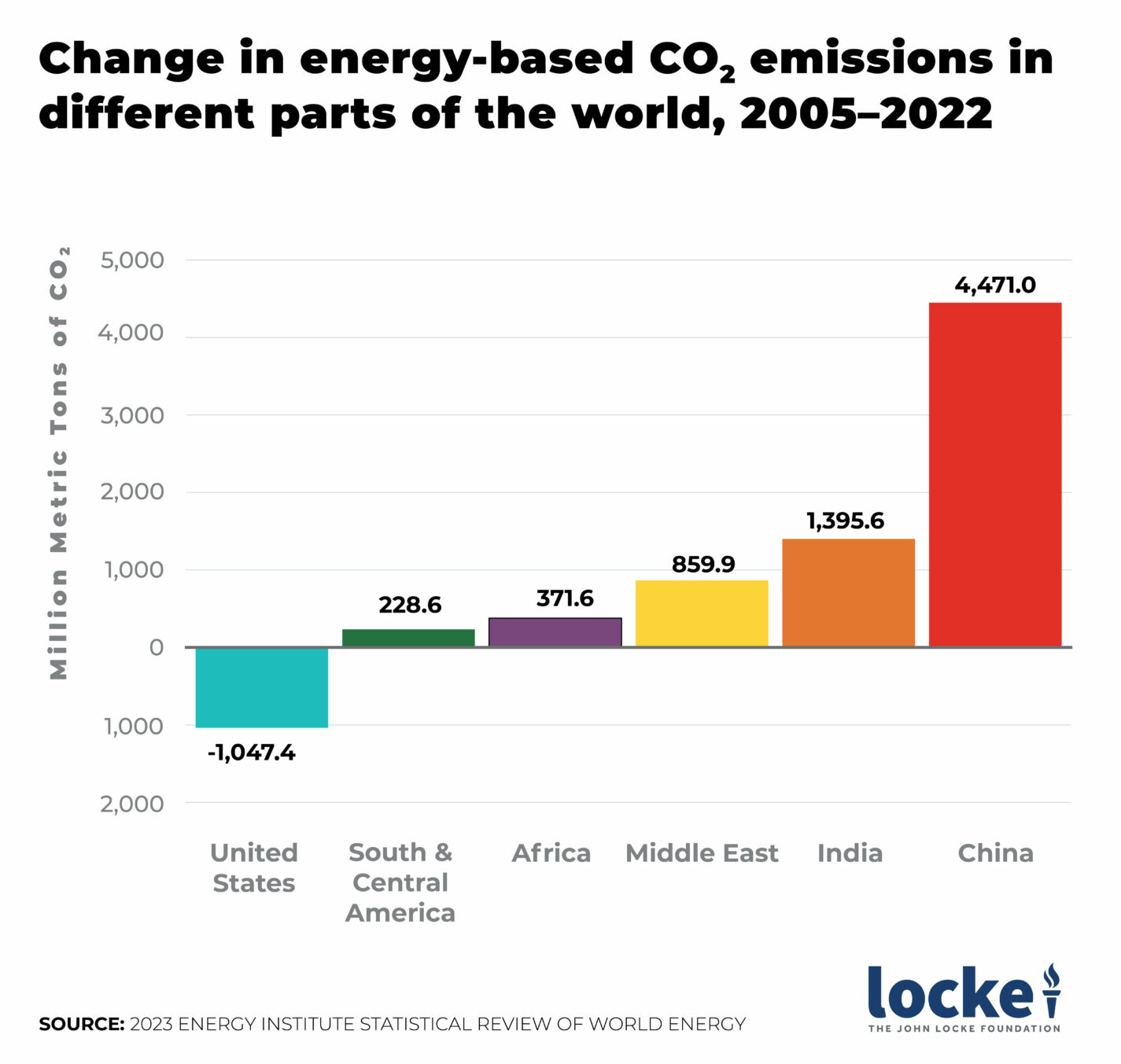

The Paris Climate Accords set emissions from the year 2005 as the baseline for measuring emission reductions. Around 2005, CO2 emissions from energy began falling in the U.S. (thanks mostly to the fracking revolution and market choices). The same is decidedly not the case for most of the rest of the world, however, and especially not China.

The maximum emissions each state could cut would still not reduce global emissions — it could only offset a tiny and dwindling bit of China’s increase.

So what we in the United States have been calling “reduced” global emissions has actually been increased global emissions reduced a little bit by our falling emissions. There’s only so much the states can cut, however. They can’t get any lower than zero. But there’s virtually no limit to how much China and the rest of the world can increase.

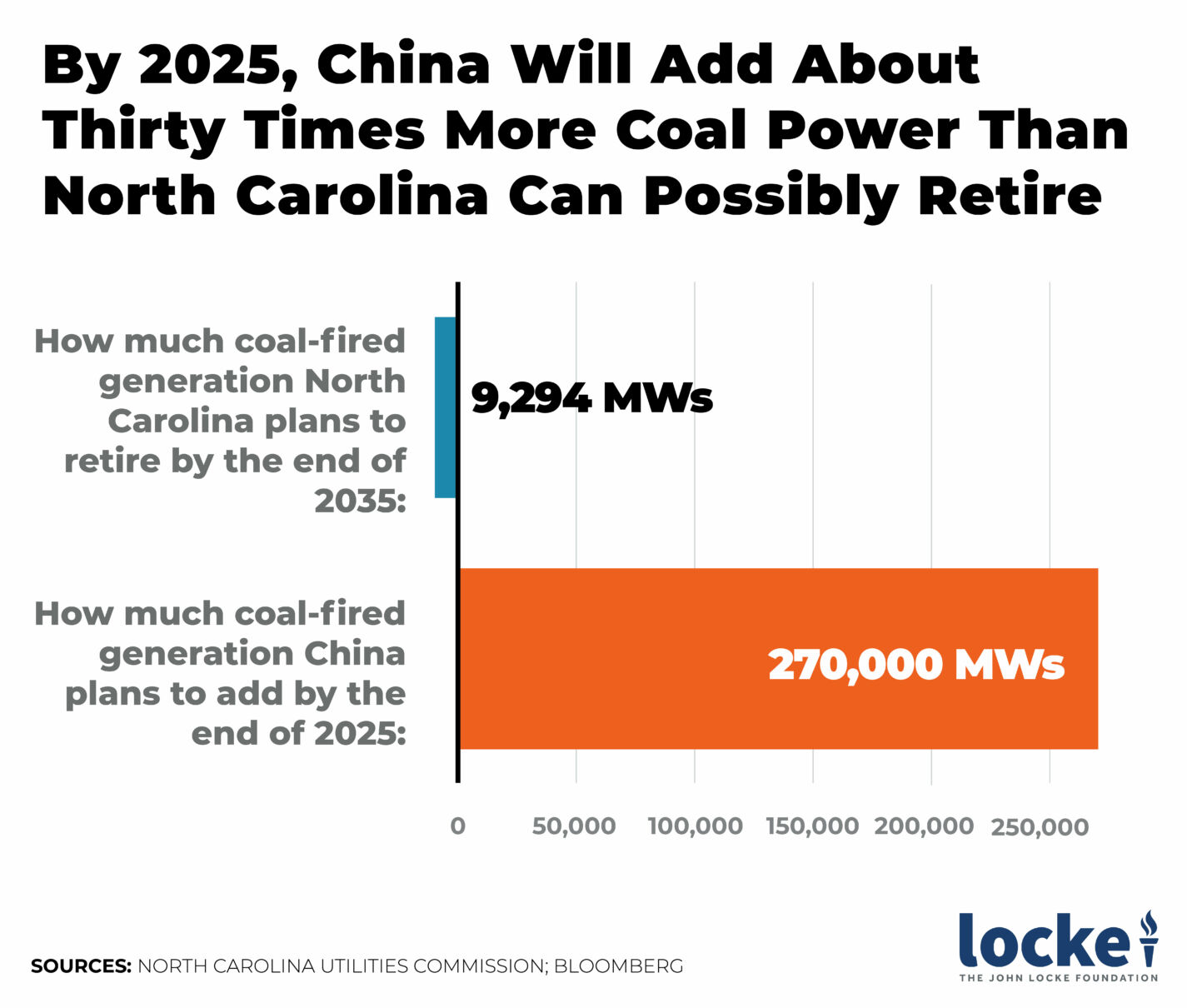

China, for example, plans to add 270,000 megawatts of new coal-fired production just in the next three years. Coal, a highly dispatchable and low-cost baseload source of electricity generation, is also very emissions-heavy. In July, Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced that China would not be bound by the Paris accords.

Emissions are global, but costs are local

Whatever impact CO2 emissions might have on weather events, it doesn’t matter where in the world they are emitted — and just as importantly, where they’re not emitted. Emissions from any particular area on earth mix across the earth’s troposphere. As explained by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, “Because GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions spread out and mix within the troposphere, the climatic impact of GHG emissions does not depend upon source location.” In terms of cutting emissions, that means any “reward” from decreased emissions cannot be exclusive to the “virtuous” place, nor can any “penalty” from increased emissions be localized to the “offending” area.

A state can cut its CO2 emissions from electricity generation down to zero but reap no conceivable benefits from it as emissions are still increasing in most of the world.

Emissions may be global, but the costs of cutting emissions are highly localized. Higher electricity bills here won’t affect families buying groceries in the Far East, but it will make it much harder for you and your neighbors.

China Carbon Time explained

What China Carbon Time does is cut to the chase for state policymakers trying to decarbonize electricity: What’s the most a state could cut, and how much of China’s huge increase would it offset? It shows how much electricity-based CO2 emissions each state could cut, based on the 2005 baseline, to reach zero (i.e., “carbon neutrality”). Then, recognizing that the most each state could do would still only offset a little of China’s increase in CO2 emissions since 2005, it answers how much the state could offset at present.

A state can destroy working power plants and impoverish and endanger its own citizens, but it won’t affect the world’s climate one bit. It can’t.

Energy emissions data for China and other nations come from the 2023 Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy. Subtracting China’s 2005 baseline emissions from its emissions level in 2022 shows that China has increased its emissions from energy by roughly 4,471.0 million metric tons of CO2. So in 2022, China emitted 4,471 million metric tons of CO2 more than it did in 2005.

Electricity-based CO2 emissions data for the states come from the various State Electricity Profiles from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), furnishing each state’s 2005 emissions baseline, representing the most the state could cut to reach carbon neutrality (i.e., zero emissions from electricity generation). Each state has reduced its CO2 emissions since 2005. If, by imposing expensive public policies, the state’s emissions were reduced to zero from their 2005 levels, how much of China’s increased 4,471 million metric tons of CO2 since 2005 could the state offset?

A challenge is how to present this information in a way that accounts for the vast differences in scale involved. So this metric sets China’s increase in CO2 emissions since 2005 in terms not of a year, but in minutes in a day. In this “day,” China emits 3.1 new million tons of CO2 per minute (4,471 tons divided by 1,440 minutes in the day). When the clock strikes midnight, that’s when China emits its last new ton.

But till what point in this “day” could a state that eliminated all of its electricity-based emissions reach its limit of offsetting new emissions from China? That is, just how long could a state put off its China Carbon Time?

Take North Carolina, for example. In 2005, the state emitted 76.7 million metric tons of CO2 from electricity generation. That would be enough to offset only 24 minutes and 42 seconds’ worth of China’s increase in CO2 emissions since 2005. The remaining 23 hours, 35 minutes, and 18 seconds would belong to China’s new emissions.

This exercise shows that:

- To get to zero emissions relative to 2005, North Carolina would need to cut 76.7 million metric tons of CO2 — but China has increased emissions by 4,471 million metric tons.

- The best North Carolina can do would only offset 1.7 percent of China’s increase.

- If all the states combined all achieved zero emissions relative to 2005, the best they all could do would offset just over half of China’s increased emissions.

For North Carolina, China Carbon Time comes shortly after midnight, at 12:24:42 a.m. No matter how many costs North Carolina’s policymakers pile on Tar Heels to cut electricity-based emissions, that’s the most they could do. As it is, North Carolina has already reduced them by nearly half with no commensurate decrease in doomsday rhetoric or policymaking.

Remember North Carolina’s Carbon Plan? The biggest feature of the plan is the retirement of over 9,000 MWs of coal-fired generation by 2035. That’s a mere one-thirtieth of the amount of coal power that China plans to add just in the next three years, as the first graph above shows.

Further implications: Costs and benefits revisited

There are several implications from this exercise. First, China’s CO2 emissions from energy are still on the increase. As they grow, it will mean each state’s China Carbon Time will arrive even earlier.

Also, it’s not just China. Energy-based CO2 emissions across Africa (371.6 million metric tons), the Middle East (859.9), and South and Central America (228.6) have all increased since 2005. India’s emissions increased by 1,395.6 million tons. The U.S. has cut a greater amount of emissions than any other nation on earth (–1,047.4 million metric tons).

So global CO2 emissions are still increasing, despite people in the U.S. now being asked to shoulder enormous costs to cut their electricity-based emissions more. A state can destroy working power plants and impoverish and endanger its own citizens, but it won’t affect the world’s climate one bit. It can’t.

It’s certainly not Americans’ business to try to offset other nations’ increased emissions by forcing further reductions in ours — and greatly reducing our own welfare in the process. And this exercise doesn’t even address the issue of whether reduced global CO2 emissions would actually result in significant decreases in destructive weather events as hypothesized. Emissions are clearly not being reduced if all we can do is chip away a bit at the overall increase.

For all those reasons, state policies forcing CO2 reductions are all cost, no conceivable benefits to their citizens. Consider: what good is closing all of North Carolina’s coal-fired power plants and doubling electricity rates on people if China is adding 30 times that amount in a fraction of the time?

The U.S. has, thanks to fracking and market choices, already reduced its volume of energy-based CO2 emissions by more than any other nation in the world. Any costs that the U.S. or individual states impose on taxpayers and ratepayers here to reduce CO2 emissions from electricity generation further would necessarily be enormous wastes of other people’s money and resources. It would gain nothing and only leave people worse off.